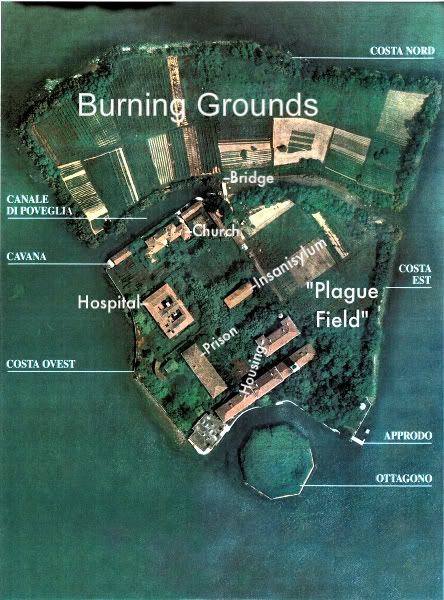

Location: Poveglia Island, 3 miles South of Venice Map

Area: 7.25 acres

Buildings: 11 structures

Closed (technically): due to poor state of buildings

Poveglia Island is a small island situated just 3 miles South of Venice in the Venetian Lagoon in Italy. Poveglia Island consists of two parts divided by a canal that has a single bridge over it. This abandoned plot of land is off limits to the tourists due to the condition of the buildings that are falling apart, but it does not mean people don't find ways to get to the island. Its main attraction is the remains of the mental institution that were opened in 1922 and closed in 1968. Many reports of paranormal activity have surfaced that keep the fame of Poveglia Island as one of the most haunted places in Italy alive and persistent. Several reality shows were filmed at this location including Ghost Adventures, Scariest Places on Earth and many more. Hospital that contains about 11 buildings on its grounds is considered to be one of the most haunted places.

Why is Poveglia Island off limits?

Currently there is reconstruction project going on the grounds of Poveglia Island by the Italian government. Dilapidated buildings are secured and reconstructed to restore to its previous significance. Additionally attempts are being undertaken to secure beaches of the island from further erosion into the sea. Hopefully it will be open soon for legal visits by tourists.

Early Settlement and Medieval Period (5th–14th Centuries)

The

earliest references to Poveglia date back to 421 AD, during the

decline of the Roman Empire, when it first appears in historical

records as a refuge for populations fleeing barbarian invasions.

Initially, it functioned as a port in the post-Roman era, but by the

7th–9th centuries, it had grown into a populated community. Refugees

from mainland cities like Padua and Este settled there, escaping

conflicts, and the island became a self-sustaining agricultural and

fishing community. Some medieval accounts suggest the first

inhabitants included hostages or prisoners of war, though this is

steeped in legend.

By the 9th century, Poveglia's importance had

increased, with a dedicated podestà (governor) overseeing local

administration as part of the Venetian Republic's central lagoon

territories. The community thrived in relative isolation, trading

with nearby Pellestrina while avoiding mainland taxes and invasions,

fostering a peaceful and prosperous existence. This era marked

Poveglia as a key settlement in the lagoon, complete with farms and

basic infrastructure.

However, this golden period ended abruptly

in 1379 during the War of Chioggia, a protracted naval conflict

between the Republics of Venice and Genoa. The island, on the front

lines, came under attack from the Genoan fleet, forcing residents to

evacuate to the safer island of Giudecca in Venice proper. Poveglia

remained largely uninhabited for centuries afterward, marking the

end of its medieval settlement phase.

The Plague Quarantine

Era (14th–19th Centuries)

Poveglia's dark association with

disease began as early as the 14th century during Europe's bubonic

plague outbreaks, though its formal role as a quarantine site

intensified later. In 1527, after a period of abandonment, it saw

sporadic use, but it wasn't until 1776 that the Venetian Republic

repurposed it as a lazaretto—a maritime quarantine station for

incoming ships, cargo, and plague victims—to prevent epidemics from

spreading to the mainland. This function continued intermittently

until 1814, with the island serving as one of three lazarettos in

Venice, as the others were overwhelmed.

During major plague

waves, including the Black Death in the 1700s and outbreaks in the

14th and 17th centuries, thousands of infected individuals were

isolated there, often left to die. Estimates suggest over 160,000

people perished on the island, with bodies burned in mass pits or

bonfires, leading to claims that the soil is composed partly of

human ashes—though this is likely exaggerated. The quarantine was

enforced rigorously, as Venice's island geography made it vulnerable

to contagions from trade routes.

In 1645, amid ongoing threats,

the Venetian government constructed an octagonal fort on the island

as part of a defensive network of five such structures in the lagoon

to repel enemy ships; four, including Poveglia's, survive today. By

the 19th century, the lazaretto evolved into a general medical

facility before shifting focus.

The Asylum and Hospital

Period (20th Century)

In the early 20th century, specifically

around 1922, the existing structures on Poveglia were converted into

a psychiatric asylum, also serving at times as a nursing home for

the elderly. Patients, often those with mental illnesses or

disabilities, were housed in isolation, and historical accounts note

that treatments could be harsh, including restraints and

experimental procedures common to asylums of the era. Legends abound

of a sadistic head doctor who allegedly tortured patients and later

committed suicide by jumping from the bell tower, driven mad by

ghosts—though these tales are unsubstantiated folklore.

The

facility later transitioned fully into a geriatric hospital under

the Italian Navy, functioning as a navy hospital with additional

military roles like a shipyard. It operated until 1968, when it

closed due to declining use and maintenance issues, leaving the

buildings to decay.

Modern Era and Haunted Legacy (Late 20th

Century–Present)

Post-1968, Poveglia fell into neglect, its

overgrown ruins attracting urban explorers and ghost hunters despite

being officially forbidden to visitors. Its reputation as "the most

haunted island in the world" or "Island of Death" grew from its

plague and asylum history, amplified by media sensationalism,

including TV shows depicting paranormal activity. Locals

historically avoided it, and finding boat captains willing to

approach remains challenging.

In 2014, the Italian government

attempted to auction the island for redevelopment, but plans

stalled. By 2025, amid overtourism concerns in Venice, the northern

part was concessioned for a locals-only public space, banning

tourists to preserve it as a haven for residents. Poveglia's history

reflects broader themes of isolation, disease control, and societal

treatment of the vulnerable in Venetian society, blending verifiable

events with enduring myths.

The Bell Tower (Campanile)

The most prominent and enduring

feature of Poveglia is its 12th-century bell tower, originally part

of the Church of San Vitale. Standing tall with a conical

terracotta-tiled spire, it rises above the treeline and serves as a

landmark visible from afar in the lagoon. Constructed in medieval

Romanesque style, the tower features simple arched openings for

bells and a clock face installed in 1745. After the church's

demolition in 1806 under Napoleon's orders (to repurpose materials

and space), the tower was converted into a lighthouse, with its

upper levels adapted for signaling. Its brick facade shows

weathering and scaffolding in recent images, indicating ongoing

decay or minor preservation efforts. Historically, it symbolized the

island's ecclesiastical center during its medieval heyday as a

self-governing community with over 800 homes, vineyards, and salt

marshes.

This structure not only anchors the island visually but

also ties into its defensive past, potentially used for

surveillance. Today, it looms over the ruins, partially scaffolded

and entangled with dead trees, embodying the island's shift from

prosperity to isolation.

The Church of San Vitale

Though

largely demolished in 1806, remnants of this medieval church

highlight Poveglia's early Christian heritage. Built in the 12th

century or earlier, it was a modest single-nave structure with stone

and brick construction, typical of lagoon parish churches. It served

the island's growing population from the 7th century, when refugees

from barbarian invasions (including Attila the Hun's hordes) settled

there. The church survived the 1378–1381 War of Chioggia, when

Genoese forces razed most of the island, but was ultimately

destroyed under French rule. Only foundational traces and the

adjacent bell tower remain, now integrated into the overgrown

landscape.

The Octagonal Fort (Ottagono)

Located on the

smallest, separate islet southwest of the main landmass, this fort

is a classic example of 17th-century Venetian military engineering.

Constructed starting in 1645 as one of five octagonal forts in the

lagoon, it was designed to control and protect entrances to Venice

from naval threats. The structure consists of an earthen rampart

reinforced with brick facing, forming a low, polygonal bastion with

sloped walls for cannon defense. No elaborate superstructures

exist—it's primarily a functional earthwork, about 100 meters in

diameter, with grassy interiors now overgrown. This

Renaissance-Baroque fortification style emphasized geometric

precision for optimal artillery coverage, reflecting Venice's

maritime republic era. It played roles in later conflicts, including

the Napoleonic Wars and both World Wars, but has since fallen into

disuse, eroded by tides and vegetation.

The Hospital and

Asylum Complex

The core of Poveglia's modern architecture lies in

its hospital buildings, originally established as a quarantine

station (Lazzaretto Novissimo) in 1776 under Venice's Magistrate of

Health. This complex evolved from simple isolation wards during the

18th-century plague outbreaks into a full psychiatric asylum and

geriatric hospital in the 20th century (1922–1968). The main

hospital is a sprawling, multi-story brick edifice with arched

windows, terracotta roofs, and utilitarian neoclassical

elements—wide corridors for patient movement, segregated wards, and

administrative wings. Brick arcades and verandas along the

waterfront provided ventilation in the humid climate, while upper

floors housed dormitories and treatment areas.

Key components

include:

Psychiatric Ward/Asylum: Converted from quarantine

facilities in 1922, featuring barred windows, isolation cells, and

rumored experimental rooms (though unsubstantiated tales of torture

abound). Institutional style with plain, functional interiors.

Prison Structures: Small detention areas tied to the quarantine era

for controlling infected individuals.

Staff Housing and

Administrative Buildings: Modest brick residences with tiled roofs,

scattered around the complex for doctors, nurses, and officials.

The complex was expanded in the 19th century as a naval hospital

under Austrian and Italian rule, focusing on contagious diseases

like tuberculosis (no operating theaters, emphasizing rest and

isolation). Post-1968 abandonment due to water supply issues led to

severe deterioration: collapsed ceilings, vandalized interiors, and

invasive greenery. A close-up view reveals the brickwork, arched

fenestration, and scaffolding indicative of its ruined state.

The Cavana and Bridge

Cavana: A traditional Venetian boat

shelter, likely from the 18th–19th centuries, built as a covered

brick archway along the waterfront for storing vessels used in

quarantine operations. Simple, arched design for practicality.

Bridge: A narrow, arched stone or brick span connecting the main

built island to the vegetated one, facilitating movement between

administrative areas and agricultural fields (once used for

self-sufficiency during quarantines).

Other Features and

Overall State

Additional remnants include plague pits (mass

graves from 18th-century epidemics, estimated to hold over 100,000

bodies), scattered ruins from medieval homes (destroyed in 1334 fire

and 1379 war), and 16th-century ship repair facilities. The island's

architecture blends defensive functionality with institutional

austerity, but its current ruinous condition—exacerbated by 50+

years of neglect—highlights themes of decay. Proposals for reuse

(e.g., as a university campus) have surfaced, but it remains

state-owned and restricted, preserving its haunting allure.

The Plague Era: Legends of Death and Undeath

Poveglia's most

infamous chapter ties to the Black Death, which ravaged Europe in

waves from the 14th to 18th centuries. Popular lore claims over

160,000 victims were quarantined here, with the dying isolated in

crude hospitals and the dead burned in massive pyres or dumped into

plague pits. Bodies were allegedly stacked and incinerated, leading

to the chilling rumor that 50% of the island's soil consists of

human ash and bones—fishermen reportedly dredge up remains and

quickly toss them back, fearing curses. In clearer waters, skulls

and bones are said to be visible beneath the surface, and mass

graves have yielded skeletons with stones clamped between their

jaws—a 17th-century practice to prevent "vampires" from feeding, as

decomposing bodies sometimes oozed blood, mimicking the undead.

Hauntings from this period dominate the folklore. Victims' screams

and moans are purportedly heard echoing across the lagoon,

especially at night, as if the tormented souls relive their agony.

One persistent apparition is "Little Maria," a young girl believed

to be a plague victim from over 400 years ago. She's described as

wandering the beach in tattered clothes, crying inconsolably, her

small figure evoking profound sorrow in witnesses. Fishermen and

rare visitors claim to spot her at dusk, her wails carrying over the

water. Other reports include huge, disembodied eyes peering from

just below the water's surface, watching boats pass by. Skeptics

note that while quarantines did occur, the scale of deaths here is

likely overstated, with primary plague activities elsewhere in the

lagoon.

The Asylum Era: Tales of Madness and the Mad Doctor

In the 1920s, Poveglia was converted into a mental hospital, housing

psychiatric patients until its closure. Legends paint a gruesome

picture: Patients reportedly saw visions of plague ghosts, which

exacerbated their mental anguish. The central figure in these

stories is the "mad doctor," an unnamed director who allegedly

conducted brutal experiments, including crude lobotomies using a

hammer and chisel driven through the eye socket. Driven insane by

apparitions of his victims, he climbed the bell tower and leaped to

his death, his body reportedly enveloped by a mysterious fog upon

impact. His spirit is said to linger, continuing his torments.

Specific asylum ghosts include:

Pietro: A patient who had both

legs amputated but raced in his wheelchair; visitors hear phantom

wheels screeching through the corridors.

Frederico: Known for his

incessant, maniacal laughter that echoes throughout the day.

Young Female Spirit: A terrified woman with a haunting expression,

forever fleeing the mad doctor's experiments; her face appears in

windows, eyes wide with fear.

Paranormal reports from the

asylum ruins describe shadows that follow explorers, unexplained

scratches and pushes, and a pervasive sense of dread upon landing.

One entry point requires crawling through an old crematorium,

heightening the terror. The bell tower is a hotspot, with phantom

ringing heard despite the bell's removal decades ago.

Modern

Explorations and Enduring Mysteries

In recent decades, Poveglia

has attracted urban explorers and paranormal investigators, despite

bans. Accounts from overnight stays describe overwhelming sorrow,

unseen forces, and auditory hallucinations. The Ghost Adventures

crew filmed there, reporting equipment malfunctions and physical

encounters. Yet, the island's true "haunting" may lie in its

neglect—ruins crumbling from indifference rather than supernatural

malice. Whether fact or folklore, Poveglia's stories continue to

captivate, blending verifiable tragedy with the allure of the

unknown.

The mass burials of plague victims on Poveglia Island are deeply

intertwined with Venice's long history of combating infectious

diseases, particularly the bubonic plague (Yersinia pestis), which

ravaged Europe multiple times between the 14th and 18th centuries.

Venice, as a major maritime trading hub, was especially vulnerable

to outbreaks brought by ships from afar. To mitigate this, the

Venetian Republic developed one of the world's earliest organized

quarantine systems, known as "lazzaretti" (named after the biblical

Lazarus, symbolizing resurrection or isolation). These were isolated

islands in the Venetian Lagoon designated for quarantining suspected

carriers, treating the sick, and disposing of the dead.

The Black

Death of 1347–1351 killed up to half of Venice's population

(estimates range from 50,000 to 100,000 deaths in the city alone).

Subsequent outbreaks in 1575–1577 and 1630–1631 claimed tens of

thousands more lives. During these crises, bodies piled up in the

streets, and authorities resorted to mass graves or cremations to

prevent further spread. Plague victims were often buried in deep

pits (fosse comuni) layered with lime to accelerate decomposition

and reduce contagion risk. In severe cases, bodies were burned in

open pyres, with ashes scattered or interred. Workers known as

"monatti" (corpse carriers) handled the dead, often under hazardous

conditions, and accounts from the time describe chaotic scenes where

the sick shared beds with the dying.

The primary lazzaretti were

Lazzaretto Vecchio (established 1423, near the Lido, serving as a

hospital for the infected) and Lazzaretto Nuovo (1468, in the

northern lagoon, for quarantine of goods and people). These sites

handled the bulk of plague victims and burials. Archaeological

excavations at Lazzaretto Vecchio have uncovered layered mass graves

dating back to the 15th century, with over 1,500 skeletons found in

trenches—some neatly arranged and shrouded in earlier layers, others

hastily dumped in later ones. These graves reflect the progression

of outbreaks: orderly at first, then desperate as death tolls

surged.

Poveglia's Role in Plague Quarantines

Poveglia

Island, a small (about 17 acres) octagonal-shaped islet located 8 km

south of Venice between the city and the Lido, entered this system

later than the main lazzaretti. Historically, Poveglia was inhabited

from Roman times until the 14th century, when residents fled due to

wars and invasions, leaving it largely abandoned. It served various

purposes over time, including as a military outpost with

fortifications built in the 18th century.

Poveglia's association

with the plague began in earnest around 1776–1793, when it was

repurposed as a temporary quarantine station (lazaretto) amid waning

but persistent plague threats in Europe. By this point, the major

outbreaks had subsided, and the original lazzaretti were being

phased out. Poveglia became known as the "Lazzaretto Novissimo"

(Newest Lazaretto), primarily functioning as a checkpoint for

inspecting ships, goods, and passengers entering Venice. Suspected

plague carriers were isolated here for up to 40 days (the origin of

the term "quarantine," from the Italian "quaranta giorni"). If

symptoms appeared, individuals were treated in makeshift facilities,

but the island was not a primary hospital like Lazzaretto Vecchio.

During its operation until 1814 (under Napoleonic rule, when the

bell tower was converted to a lighthouse), Poveglia handled

occasional infected vessels. Historical records indicate that only a

few dozen plague victims actually died on the island—far fewer than

the thousands processed at the older sites. It later served as a

hospital for other contagious diseases like tuberculosis until 1969.

Details of Mass Burials on Poveglia

Contrary to popular lore,

Poveglia was not a site of extensive mass burials during the height

of the Black Death or major 16th–17th century outbreaks. Those

occurred primarily on Lazzaretto Vecchio and Nuovo, where mass

graves have been archaeologically confirmed. The few plague-related

deaths on Poveglia (from the late 18th century onward) would have

been handled through standard Venetian protocols: bodies buried in

small pits or cremated to contain infection. No large-scale

excavations have occurred on Poveglia itself, so physical evidence

of burials remains unconfirmed, but local accounts suggest one or

more modest "plague pits" may exist, possibly containing remains

mixed with lime or ash.

Burial practices during Venetian

plagues generally involved:

Initial Handling: Corpses were

collected by monatti using hooks or carts, often from homes or

streets, and transported by barge to isolation sites.

Grave

Types: Early graves were rectangular trenches with bodies aligned

and wrapped in sheets for dignity. As crises worsened, they became

chaotic pits where bodies were stacked haphazardly, sometimes up to

several layers deep.

Cremation: When space ran out, pyres were

lit on-site. Ashes were scattered or buried, contributing to soil

composition rich in human remains (though claims of 50% ash in

Poveglia's soil are unsubstantiated and likely exaggerated).

Sanitation Measures: Lime was sprinkled to neutralize odors and

pathogens. Graves were marked with warnings like "Ne fodias" ("Do

not dig") to prevent disturbance.

On Poveglia, given its

smaller scale, burials were likely limited to individual or small

group interments rather than vast mass graves. The island's soil,

overgrown with vegetation today, may contain bone fragments that

occasionally surface or wash ashore, as reported by fishermen, but

this is common across the lagoon's former quarantine sites.

Myths vs. Historical Accuracy

Poveglia's reputation as the

"Island of Death" or "Island of Ghosts" stems from sensationalized

stories, amplified by modern media, ghost tours, and TV shows.

Common claims include:

Over 160,000 plague victims buried or

cremated there, with human ash comprising half the soil.

Mass

burnings of living victims to curb spread.

Hauntings by plague

spirits, with screams echoing from pits.

These figures and

tales are largely inaccurate and inflated. The 160,000 estimate

appears to conflate Poveglia with the cumulative deaths across all

Venetian lazzaretti over centuries. Historical evidence shows

Poveglia's plague role was brief and minor, post-dating the worst

outbreaks. Mass graves and major excavations are documented on

nearby islands like Lazzaretto Vecchio, not Poveglia, which has not

been systematically dug due to its private ownership and restricted

access. Myths likely arose from its later use as a mental asylum

(1922–1968), where unsubstantiated stories of patient abuse merged

with plague lore.

Despite the exaggerations, Poveglia symbolizes

the grim reality of plague management: isolation, despair, and hasty

disposal of the dead. Today, the island is uninhabited, overgrown,

and off-limits to visitors, its ruins (including a crumbling church

and hospital) evoking a haunting reminder of Venice's plague-scarred

past. Local fishermen avoid it, citing curses or bad luck, though

this may stem more from superstition than fact.