Location: Londres 247, Coyoacán

Subway: Coyoacán

Tel. 5554 5999

Open: 10am- 5:45pm Tue- Sun

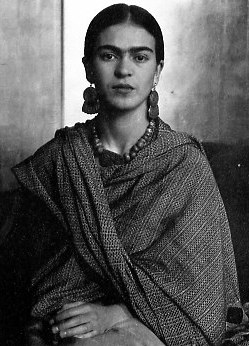

July 6, 1907 – July 13, 1954

The Frida Kahlo Museum is the most representative

cultural venue of the Mexican artist, as well as a container for an

important part of her artistic and conceptual legacy. It is a house

museum located in the Carmen Neighborhood of the Coyoacán Mayor's

Office, which corresponds to one of the most traditional and beautiful

neighborhoods in Mexico City. A few blocks from the museum, the center

of Coyoacán is located.

Also known as the Blue House, it is one

of the busiest museums in the area. The building, which today protects

and exhibits a collection of pieces of various kinds, belonged to the

Kahlo family since 1904. Four years after the painter's death, in July

19582, it opened its doors to the public as a house museum.

Frida

Kahlo (1907-1954) lived in the Blue House for most of her life;

initially, with her family and years later, with Diego Rivera

(1886-1957). Likewise, characters from the artistic and intellectual

environment of the first half of the twentieth century, both Mexicans

and foreigners, stayed at the residence, attracted by the captivating

couple of artists.

Different figures participated in the

construction of the building, including the painter and functionalist

architect Juan O'Gorman, a great friend of both Diego and Kahlo. The

museography was carried out by the writer, poet, museographer and

Tabasco politician Carlos Pellicer, who is also close to the couple. The

administration of the museum was entrusted to the Diego Rivera and Frida

Kahlo Museum Trust, attached to the Bank of Mexico, constituted by

Rivera himself in 1957. In this regard, this entity affirms that the

planning of the operation of the enclosure was developed “with the

purpose of exhibiting work, illustrating the personality and

perpetuating the memory of Frida Kahlo.”

Frida wanted to leave

her house as a museum, for the learning and enjoyment of her beloved

Mexico. For this reason, Diego organizes, in what was the painter's

home, the Frida Kahlo Museum. Following the will of his wife, the

muralist began this task a few months after Frida Kahlo died, that is,

in the last months of the year 1954.

Since the inauguration of

the Museum in July 1958, the Blue House has exhibited the environment in

which Frida was inspired for her artistic creation, as well as her

personal objects. The latter, it took to be fully unveiled. Before he

died, Diego ordered that the bathrooms of the Blue House not be opened

until fifteen years after his departure. In these spaces, Rivera had

protected part of the couple's documents, as well as certain of Frida's

belongings. Obeying Rivera's indication and extending it over time,

Dolores Olmedo, the muralist's patron, declared that as long as she

lived, she would not open these places.For this reason, only one hundred

years after Frida's birth and fifty after Diego's death, the objects

that Rivera had so manifestly enclosed were finally exposed to the

public, which are known to this day as the Treasures of the Blue House.

Nowadays, along with certain paintings by both artists, notable

works of folk art, pre-Columbian sculptures, elements of Frida's daily

life, part of her magnificent collection of ex-votos, photographs,

documents, books and furniture are displayed in the Blue House.

Likewise, two traveling exhibitions commissioned by the Museum, called

“Frida Kahlo, her photos” and “Appearances Deceive”, are samples of

excellent quality, which disseminate nationally and internationally, the

legacy of Frida and Diego safeguarded in the Blue House.

The poet

and historian Luis Roberto Vera admits that visiting the house where the

artist developed both professionally and personally is of great interest

because “there is a concordance between her pictorial world and her

lived world".

The beautiful garden of the residence also has a

peculiar history and is an essential part of the Blue House. Currently,

when crossing it, you can access the exhibition of Frida's Dresses.

The Blue House is located in a corner of the Colonia

Del Carmen; a neighborhood of 170 hectares that was once part of the San

Pedro Mártir Hacienda. Around 1890, this place received its name in

honor of Doña Carmen Ortiz Rubio de Díaz, the wife of President Porfirio

Díaz. It is located within the Coyoacán City Hall, whose history dates

back to pre-Hispanic Mexico.

Its name comes from the Nahuatl

Coyohuacan, “place of the coyote owners”. According to the Mexican

philosopher and historian Miguel León-Portilla, the region was formerly

consecrated to Tezcatlipoca, a deity with the power to transform into a

coyote at night. The eruption of the Xitle volcano, which occurred

between 245 and 315 A.D., covered this region, as well as many others in

the Anahuac basin, with ash and basalt stones, which were used in many

later buildings in the area.

Despite having had a constant

activity since pre-Columbian times and throughout the viceregal period,

by the time the Mexican War of Independence came to an end, the

territory of Coyoacán had become quite uninhabited. It was from the

government of Díaz, that Coyoacán developed again, until it became what

it is today.

Between 1917 and 1923, the Nursery Park and the

Outdoor Painting School were created. In 1926, the opening of Mexico

Coyoacán Avenue led to the connection between Colonia Del Carmen and

Colonia Del Valle, as well as other neighboring colonies. A little more

than a decade later, the paving of important avenues began, such as

Miguel Ángel de Quevedo. By 1929, Coyoacán was already considered one of

the most important delegations (today mayoralties) of the Federal

District (today Mexico City).

In 1972, the Center of Coyoacán was

declared a historical zone and in 1990, a Protected Monumental Zone.

Today, Coyoacán is home to the quintessential intellectual and cultural

neighborhoods of Mexico City. Its streets have been the scene of the

life and transit of outstanding figures of the Mexican cultural

environment such as Rina Lazo, Emilio “Indio” Fernández, José Clemente

Orozco, Aurora Reyes, Luis Buñuel, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jorge

Ibargüengoitia, among others.

Carl Wilhelm Kahlo, known as

Guillermo Kahlo, embarked for Mexico as an immigrant at the age of 19.

The young German was motivated by the growing and economically

successful German colony already existing in Mexico, which was

proliferating by the second half of the nineteenth century, as well as

by reading the chronicles of the German explorer, researcher and

scientist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1869). Likewise, it is possible

that reports about the expansion of the jewelry industry in Mexico have

prompted Guillermo to try his luck in the Aztec country. This, coupled

with the fact that - according to Frida herself - her mother had died,

and she never had a good relationship with her stepmother in Germany.

In 1891, Wilhelm arrived at the port of Veracruz, endowed with the

knowledge inherited from a vast genealogy of jewelers. Accordingly, he

began working at La Perla jewelry store, located in the center of the

country's capital. In 1893, he married María Cardeña, who died giving

birth to their third baby, in October 1897. In February 1898, Wilhelm

married Matilde Calderón, with whom he had four daughters; Frida was the

third of them. Most likely, it was his new father-in-law who introduced

him to the world of photography. Thus, the young Kahlo was soon working

as a reporter for several national magazines.

His career as a

photographer developed satisfactorily and allowed him to acquire in 1904

a land of 800 square meters on the corner of Londres and Allende

Streets, which was once owned by the religious order of the Carmelites.

On this property, Guillermo, the name by which he called himself Wilhem

shortly after arriving in Mexico, built his house at number 75 on block

36, located at the northeast corner of the intersection of London and

Allende streets. According to the Mexican chronicler of Belgian origin,

Luis Everaert Dubernard, there were still not many houses in the area

room:

"With a facade facing both streets, a one-story house was soon

built on the property, on a low-rise basement, with a C-shaped floor

plan around a courtyard to which the rooms faced, aligned one after the

next (...). For a long time, that construction that I remember with the

facades always painted ultramarine blue was the only one in the entire

block."

Before Guillermo's arrival in Mexico, an enterprising and

visionary German businessman, Sigismundo Wolff, acquired the land of the

then Hacienda de San Pedro. Thus, the transformation of the property

could begin, in the Colonia Del Carmen, around 1886. Possibly, Wolff got

this territorial concession, precisely to promote the settlement of the

Carmen colony, urbanizing it in a Moderna way. He facilitated the

commercialization of the lots through agents, information and sales

offices, with plans of the entire colony or fractions of it. It offered

payment facilities and mortgage-based financing plans. His projects

turned out to be an excellent investment, both for him and for the new

owners. One of those plans, an example of professional urban planning

for the time, is preserved in the Historical Archive of Mexico City.

Once in the Mexican capital, it was probably the knowledge of Wolff's

generous contribution and its importance for the establishment of the

Colonia Del Carmen, which prompted Kahlo to build her home there, as a

way to stay close to her German roots. When Guillermo settled in

Coyoacán, he found an area that obeyed the urban planning canons present

in cities europeas.De agreement with Everaert:

"The map shows an area

with an orthogonal line of very wide streets, that is, at right angles,

north-south and east-west orientation, and rectangular blocks of 60 by

100 meters on each side, with typical lots of 1000 square meters, a

large public park in the center, and with the nomenclature of streets

named after heroes of Independence and European capitals."

It is said that the original design of the property

was rectangular in shape and included some outdoor spaces. According to

Hayden Herrera, the structure of the house, its single floor, its smooth

ceiling and its “c”-shaped plan assimilated to a nineteenth-century

design.

It is not known exactly when, or why, the exterior walls

of the house were painted blue. In October 1932 the residence was

already endowed with this color, according to the following quote,

originally from Lucienne Bloch's Diary: "What a house! All shiny blue

with pink corners, with green windows and a central courtyard with

cacti, orange trees and Aztec idols”" When she wrote this impression,

the American muralist was visiting the Coyoacán residence. He had

traveled generously accompanying Frida to witness the death of her

mother, which also happened in September of that same year, 1932. It is

also documented that, in January 1937, when the couple of Leon Trotsky

and Natalia Sedova arrived to stay at the residence, the house was still

painted blue. This is how Trotsky's personal assistant at that time,

Jean Van Heijenoort, tells it: “From the airport I took a taxi to

Coyoacán. In a blue house located on London Avenue, which was surrounded

by policemen, I met with Trotsky and Natalia.”

There is no doubt

that the color of the house is one of the attributes that facilitated

the identification of the house, when it began to become nationally and

internationally famous. Its popularity began, probably, on the occasion

of the arrival of the Russian revolutionary. This visit that lasted for

two years attracted press, as well as social and political activity to

the property.

It is estimated that the beautiful garden of the

house began to take shape in an indefinite period between 1933 and 1936.

In 1937, Diego acquired the adjacent property, previously uninhabited,

of one thousand and forty square meters. This purchase was made possible

thanks to an anonymous donation received by Diego Rivera, intended to

finance the implementation of measures to guarantee Leon Trotsky's

comfort and safety during his confinement. Likewise, the windows facing

the street were boarded up from the inside with adobe blocks, a security

tower facing London was built and the height of the perimeter fence was

raised considerably. Thanks to these infrastructural modifications,

Trotsky and Natalia were safe in the Blue House. The Soviet

revolutionary and his wife stayed there from January 1937 to May 1939.

During this period, Frida and Diego did not live in the Blue House, but

in their residence in San Ángel, which is now the Diego Rivera and Frida

Kahlo Studio House Museum.

In 1941 Frida and Diego settled in the

Blue House; the former permanently and Diego alternating with the

residence of San Ángel. In the mid-1940s, Diego had the wing of the

house built on the Allende Street side. In the garden he built a

fountain, a step pyramid, a fourth container of archaeological pieces

and a water mirror.

In 1946, advised by Juan O'Gorman, the

muralist commissioned basalt stone to be used for the construction of a

new studio, of avant-garde Mexican design. O'Gorman also collaborated

with Rivera to make possible the architectural design that the painter

wanted for two new bedrooms, adjacent to the Studio, and a new terrace.

The latter was particularly impressive in terms of its dimensions and

materiality. The intellectual confidence that Rivera had for O'Gorman

was born after visiting one of the houses that the functionalist

architect designed. About this current, Maestro Rivera said:

"the

architecture realized by the principle of the most scientific

functionalism, is also a work of art. And since for the maximum

efficiency and minimum cost (...), it was of enormous importance for the

rapid reconstruction of our country and, therefore (according to Maestro

Rivera himself), it gave beauty to the building.”

The architectural and decorative style of the Blue

House has been described as eclectic, perhaps because it does not

classify each of its constructive additions. However, if something is

eclectic by bringing together different trends, then the Blue House

could be it.

The property is the result of the combination of two

currents that contrast with each other, without disqualifying each

other: that of the affluent middle class of the late nineteenth century

(although the House was built at the beginning of the twentieth century,

its aesthetics are typical of the previous century) and the Mexican

avant-garde style created by Rivera and O'Gorman. Today, both designs

and construction methods look unified in a single domestic scenario.

In principle, the House responded to the ornamental canons of a

society that sought to absorb whatever was foreign. Thirty years after

its construction, its modification began, with the aim that both the

architecture and the decoration of the house cited the national. The

most decisive changes can be classified into the following stages: the

extensive initial period, from 1904 to 1936, Leon Trotsky's stay, from

1937 and the construction of the Studio, from 1946 onwards.

The only photographs that exist of the building at the

time of Guillermo Kahlo are in black and white. However, this does not

prevent ensuring that the facade of the house, in its beginnings, was

white or of some very faint pastel tone. The visual archives of the

house show a lattice, a molding, doors and windows adorned with dark

frames, possibly in the color of almagre red or sepia. This tonality

obeyed the popular style of the properly Mexican country houses. There

are authors, as is the case of Adriana Zavala, who describe the house in

its first stage as neoclassical. Beatriz Scharrer agrees with this

proposal:

Although it seems strange today, the exterior facade of

the house was neoclassical and also sported the duality of colors

already explained. On a light background, there were contrasting darker

elements such as the frieze of alternating brick heads, the top of the

corner of the house from where the south and west fronts started and the

fretwork that ran along the entire length of the facade delimiting the

interstices of the walls and crowning the windows.

Scharrer also

points out that these characteristics were representative of the

architecture of the Porfiriato, which makes perfect sense considering

that the professional rise of Frida's father, Guillermo Kahlo, took

place during that time.

The exterior view of the building was

characterized by its rectangular windows that reached the floor: four

windows were distributed on each side of the square of the house and a

distinctive window, belonging to the kitchen space, shone on the facade

facing Allende Street. The openings were richly decorated with false

balconies and garigoleted wrought iron railings. A volcanic stone

valance adorned the lower part of the house and, on the contrary, the

cornice exhibited a row of bricks.

The Mexican Revolution

dramatically changed the economic situation of the Kahlo-Calderón

family. Thanks to the help of an antique dealer from the city center,

they sold the French-made furniture in the living room. Some time later,

the couple found themselves in need of renting rooms and even mortgaging

the family house, which they had built during past and prosperous times.

The property was in the name of Matilde Calderón, Frida's mother, so we

know that such a decision had to have been made by both members of the

marriage.

About a year after Frida married Diego, the painter

settled the debt of the house, which became Frida's property. A document

from the Federal District Treasury of the year 1930 confirms the change

of owner of the house located in London number 127. It had ceased to

belong to Matilde Calderón de Kahlo and was now in the name of Frida

Kahlo de Rivera.

The couple of artists did not inhabit the Blue

House after having joined, but until 1931 when they were temporarily

installed. After spending a few weeks in Coyoacán, they traveled to New

York and later to Detroit. In 1933, they went to live in the

functionalist house that O'Gorman designed for them in San Ángel. During

this period of the couple's itinerant stay in different places, Frida's

father, Guillermo Kahlo, lived in the house in Colonia Del Carmen with

his youngest daughter Cristina, and his grandchildren Isolda and

Antonio.

Without prejudice to the above, and according to the

historian Beatriz Scharrer, it was Diego and Frida who, little by

little, gave the residence the particular aesthetic that characterizes

it to this day. They impressed on him their admiration for the peoples

of Mexico with colors and decoration of pre-Hispanic and popular art.

In the autumn of 1936, Diego Rivera convinced the then

President of Mexico, Lázaro Cárdenas, to grant the Russian revolutionary

Leon Trotsky political asylum in Mexican territory. Trotsky was

suffering at that time and for many years, the bitter persecution of

Stalin.

With Trotsky's arrival in Mexico in January 1937, and

anticipating the constant threat to which he would be subjected, Diego

ordered alterations to the Blue House, for security reasons. A

watchtower and a police booth were built. In 1938 the adjacent property

was acquired, which prior to the acquisition constituted a high-risk

front, being uninhabited.

The modifications were not only

functional, but also stylistic. In opposition to the architectural

custom of the porfiriato, in the twenties the imitation of foreign

models was abandoned. On the contrary, now it was sought to rescue and

create a properly Mexican identity, based on pre-Columbian culture and

popular art. It is equally likely that the search for a new aesthetic

for the Blue House was partially motivated by the intention of visually

aligning with the sociopolitical convictions of the Russian

intellectual, only in those aspects that were shared by the pair of

artists. In other words, we had to get rid of everything that gave the

appearance of being bourgeois.

A photograph from 1938 shows how

the walls of the Blue House were flattened. The frieze and the fretwork

that used to adorn the facade were eliminated. Only the top finial was

preserved. The garigoleted bars on the windows were replaced by round

bars painted green. The pots that were on the lattice were removed and

replaced with magueyes and pre-Columbian pieces.

In January 1941,

when both artists Frida and Diego returned to live more or less

permanently in the Blue House, the largest room in the building

(currently room 1 of the Frida Kahlo Museum) was Diego's studio. In the

next room was the then study of Frida; the present room 2 of the Museum.

Here, the artist writes that it was particularly where she was born,

although the latter is not, to date, reliably documented.

The

house also included a guest room and another that contained Frida and

Diego's beds. Frida's bed had been modified in 1925, by Matilde

Calderón, to accommodate her daughter's needs after the severe accident

that left Frida immobilized for many months. Guillermo Kahlo's then

photographic studio occupied what was originally a bathroom, a pantry

and the hallway. Part of the land acquired to guarantee Trotsky's safety

was used to expand the service yard and open a hallway to Allende

Street. A terrace, cellars and bathrooms were also added. Neither the

dining room nor the kitchen underwent structural modifications, but

aesthetic ones: the braziers and the backsplash were decorated with

handmade talavera mosaics. Wooden storage rooms painted yellow were

added and elements were acquired that highlighted the Mexican style that

the couple wanted to impregnate in their home. Among the acquisitions

that were occupied and displayed in the residence at this time, which

are still on display today, we find table linens, kitchen dishes,

tableware, wooden spoons, copper pots, earthenware pots, blown glass

vases and stone molcajetes. According to Graciela Romandia de Cantú, the

couple not only used these objects in their daily life, but also

collected pieces of folk art, “which were pleasant to their developed

artistic senses and nationalist inclinations,” to which they gave a

decorative function that continues to be the protagonist in the house.

In 1945, Frida and Diego decided to design a new

extension for the house and it was O'Gorman who was again in charge of

the constructive design of it. This building, completed in 1946, would

encompass what had been the service courtyard during the previous stage

and would become two new bedrooms, a bathroom and a new studio for the

couple of artists. Today, in the Frida Kahlo Museum this section is

known as the Blue House Studio, in which materials and workspaces of

both artists are appreciated, as they arranged and used them at this

stage of their lives.

Juan O'Gorman, a muralist and architect,

met Diego Rivera around 1922. At that time, Rivera was almost twenty

years older than him. They coincided when Rivera was making the mural of

the Bolívar Amphitheater at the Old San Ildefonso College, formerly the

National Preparatory School. At the age of 24, O'Gorman designed the

first functionalist residential building in the country, which left

Rivera impressed with the new aesthetic order of modernity.

Consequently, in 1931 the painter commissioned this architect to build

his house-studio in a neighborhood of the Álvaro Obregón Mayor's Office,

already then known as San Ángel Inn. This house is today the Diego

Rivera and Frida Kahlo Studio House Museum. In 1942, Rivera trusted his

architect friend again for the initial plans of what would be the

majestic Anahuacalli. At the end of the day, Rivera had the professional

collaboration of O'Gorman throughout the design and construction process

of his posthumous work, which would be inaugurated 22 years later as the

Diego Rivera Anahuacalli Museum.

Returning to the third stage of

the Blue House, a deposit of basalt stones was located in the vicinity

of Coyoacán. It was a relatively cheap material, which required little

maintenance. Diego, inspired by the volcanic stone that had been used by

the Aztecs to build pyramids and carve ceremonial pieces, asked O'Gorman

to cover the new construction with carefully cut blocks of this stone.

This decision, as well as several of the stylistic options that are

currently appreciated in this third stage of the house, were a

reflection of Frida and Diego's preference for environments that clearly

referenced the Mexican; whether it was the traditional, the

pre-Columbian or even the aesthetics of Moderna Mexico.

The

studio was decorated with sculptures, also pre-Columbian. Outside the

studio, 4 patios were built; 2 uncovered and 2 roofed. In the covered

patios, which functioned as meeting rooms and outdoor dining, Frida and

Diego literally "embedded” their style. Both artists designed original

mosaics for the ceilings. That ceiling that illustrates the eye, the

clock, the moon and the sun was Frida's design, while the one with the

oz and the hammer was Diego's conception. Both artists also embellished

the walls of these outdoor patios by adding sea snails and other

decorative elements, such as built-in jugs, to their walls.

This

new architectural space and the original house were connected by an

internal staircase made of basalt, built adjacent to the outside of the

kitchen, which in turn frames a low-level room, of very original design

for the time. Due to its geometry, this space is currently known in the

Frida Kahlo Museum as the “staircase cube”.

In 1953, after part

of her right leg was amputated, Frida had ramps added that started from

the atrium of the garden and made it easier for her to access the

original section of the house. He began to have difficulties accessing

the new studio, because it was reached by stairs. She solved it by

moving to the smaller of the two new rooms, located adjacent to the

study, from which she could move on her own. Frida died in this room on

July 13, 1954.

The original garden of Guillermo Kahlo's house

emulated the nineteenth-century European style. The layout of the house

around a central atrium goes back to the tradition of interior

courtyards in the houses of the first generations of Spaniards living in

Mexico, which were in turn inspired by the Moorish atriums of cities

such as Seville, Cordoba and Cadiz.

The first evidence of a

garden in Frida's childhood home comes from family photographs taken at

the beginning of the twentieth century. In them, you can see the lower

balcony and the patio below it. Among its elements, plants such as

roses, cordylines, philodendrons, palms and bananas stand out. According

to the fashion of that time, the garden had to harmonize with the

architectural structure of the residence. Accordingly, in Coyoacán's

house, numerous terracotta pots lined the edge of the balcony.

Some photographs taken in the thirties reveal that orange trees, carved

columns and new potted plants were added. Although Diego and Frida did

not inhabit the Blue House during that time, it is most likely that

Guillermo would have dedicated himself to documenting the changes that

were the decision of the artist couple.

With Trotsky's arrival at

the Blue House and the well-known purchase of the lot next to it, the

wall dividing the two plots of land was removed and the garden, which

now had an area of 800 square meters, was extended. Among the books of

Frida that remained in the collection of the Frida Kahlo Museum, there

are some of botany. It follows from this that it is possible that the

artist has acquired them to document herself regarding the possibilities

offered by an extensive garden. She and Diego planted both domestic and

imported species; among them, a wide variety of cacti (maguey, cactus,

'viejitos’, biznagas and yucca), fruit trees (orange, quince and

pomegranate) and flowers of various origins. Likewise, Frida and Diego's

pets were added to the garden, including two spider monkeys, a pair of

parakeets, another pair of turkeys, an eagle, a deer called Granizo and

six dogs, mostly from “Mexican hairy dogs” or xoloitzcuintles. Some time

after Frida and Diego married for the second time, in 1941 Rivera

supervised the construction of a step pyramid to permanently exhibit a

selection of his pre-Columbian sculptures. At the central point of the

entrance to the garden, a monolithic figure in the form of a stone hoop

was erected, also of pre-Hispanic origin, of those that were used as a

basket in the pre-Courtesian ball game. There is also a small altar to

Tlaloc in the garden and a kind of baptismal font decorated with a

quincunx border (a symbol used by the ancient inhabitants of Mesoamerica

to designate the directions of the universe: east, south, west and

north, in addition to the center, which functioned as the axis of the

world or axis mundi). Finally, the couple had a pond and a small room

built with a stone-encrusted front in the shape of Tlaloc heads and two

snake heads in the corners.

In 1946, a series of courtyards

already described earlier in the present text were built; some covered

and others exposed. Sections of the walls of the garden courtyards were

covered with stucco, painted blue and framed with tezontle. Towards the

end of her life, Frida moved to the room that had the best view of the

garden, and ramps were installed that allowed the artist to move between

the original section of the house and the central atrium. “The winding

paths in the garden, which still exist today, were specifically designed

so that (Frida) could cross them in a wheelchair.” Shortly after the

inauguration of the Museum, the interest that continues today arose, to

know the plant species that exist in Frida's garden. This research has

been nourished by the fact that many of the artist's masterpieces

include lively representations of plants that still inhabit the garden

of the Blue House. A census made in 2018 to the existing plants, shows

the great variety of origins that the living elements of the garden

have. Jacarandas, bougainvilleas, magnolias, thunders, yuccas, aguates,

cedars, ash trees, medlars, ficus, oaks, Brazil nuts, acacias, lemons,

pear trees, plums, laurels and palms have been recognized. Of the total

botanical species that were growing in the garden of the Blue House for

the census year, 56% originate from outside the American continent, 22%

come from Mesoamerica and the remaining 22% come from other areas of

America. Regarding the number of botanical specimens, the percentage

ratio turned out to be interestingly different. Of the 100% of specimens

that inhabit the garden of Frida's home, 45% are Mesoamerican, 41% are

native to areas not located on the American continent and 14% are

specimens of species that come from other parts of America.

The House Museum allows its visitors to discover the

deep relationship that exists between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera,

their paintings and their home. The rooms show part of the work of Frida

and Diego Rivera, who also lived there.

Among the highlights of

the House are Frida's beds: the day and the night. The first one has a

mirror on the lintel, which the artist used to paint her self-portraits

while she was immobilized from the column due to the terrible accident

she had. The bed at night, was the one that Frida occupied during the

last years of her life, in which she spent most of the time prostrate,

therefore she needed to change her place every certain amount of hours,

to avoid injuries by being in a horizontal position for a long time.

Another attraction of the Museum is Frida's Studio, where part of

the residence's library can be seen, which brings together volumes that

belonged to Frida, her family, as well as Diego Rivera. The Kitchen of

the Blue House, is one of the most traditional spaces of the Museum in

terms of its aesthetics; the vessels, dishes and utensils of Mexican

artisanal manufacture, are beautifully exposed and reflect the

gastronomic lifestyle of the artist and her family. Although at the time

Frida and Diego lived, gas was already used in the kitchens, the couple

preferred to preserve the stove of the Blue House based on wood,

probably to enjoy the preparation of meals in the traditional style.

Each room of the House reveals the clear preference that the couple

had around the Mexican aesthetic. Thus, for example, pre-Hispanic

sculptures are exhibited in several places of the Blue House. Likewise,

there are more than ten representations on cardboard, called "Judas";

they are great characters that hang on the walls. The artists' Studio

preserves paintings, brushes, pencils, books and notebooks, as they were

once used. In this way, the personalities of Frida and Diego are

represented in their home, leaving their essences in each place.

The artworks of Frida Kahlo that are exhibited in the exhibition halls

give an account of the work process and the pictorial evolution of the

artist during her professional life. Many of these works, probably most

of them, are unfinished. This is because Frida Kahlo sold most of the

paintings she made in their entirety during her lifetime. However, in

the Blue House there are three masterpieces of the artist's career that

are finished: Portrait of my Father (1941), Viva la Vida (1954) and

Still Life; a very special painting in a round frame, from the year

1942.

During his lifetime, Rivera left everything arranged so

that when he and Frida died, the house would become a museum. The

bathrooms of the residence were closed as cellars; the muralist

indicated that they could be opened only fifteen years after his death.

That time was extended to forty-eight years, and when these spaces were

opened, hundreds of documents, photos, dresses, books and accessories

were discovered. It was necessary to annex and condition the building

adjacent to the residence in order to exhibit the treasures found.