Location: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee

As the Trail of Tears (English Trail of Tears,

Cherokee ᎨᏥᎧᎲᏓ ᎠᏁᎬᎢ getsikahvda anegvi) the expulsion of North

American natives ("Indians") from the fertile southeastern woodland

of the United States in the rather barren Indian Territory in what

is now the state of Oklahoma is called. The deportations of Native

American tribes represent a historical turning point and mark a low

point in relations between Native Americans and the United States

government.

The expulsion took place against the background

of the increasing land requirements of the European settlers from

1800 and the associated expansion of the North American borderland.

The resettlement affected the Muskogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw,

Choctaw, and Seminole peoples, also described as the "Five Civilized

Nations" because of their adaptation to the colonists' way of life.

In keeping with United States Indian policy, legislation covered

displacement through the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Through

treaties negotiated by President Andrew Jackson, the Indian peoples

were subject to cession, land exchange, or sale of their ancestral

lands in the southern states between 1831 and 1839 or forced to

evict by the use of the military.

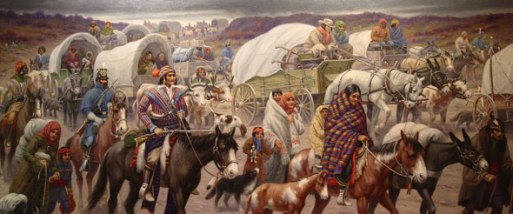

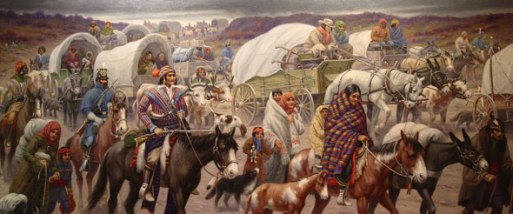

The resettlement was

organized in treks and followed various routes to the west,

accompanied by American troops. On the way to the newly established

Indian reservations, over a quarter of the expellees and the

Afro-American slaves accompanying them died of disease, exhaustion,

cold and starvation. The consequences for the indigenous people were

devastating and lasted well into the second half of the 20th

century. In addition to the serious decimation of the peoples, the

tribes closely linked to their ancestral homeland experienced a

cultural and spiritual uprooting. The peoples were divided into

eastern and western tribes. In the assigned areas, there was further

fragmentation of the peoples and conflicts with other resettled

tribes, and as the United States expanded westward, further

displacements.

Despite calls from Native American peoples

affected by the evictions, the United States government has not (as

of June 2020) issued a statement on its involvement in the

deportation and the associated consequences. However, two of the

routes of the Cherokee Trail of Tears were added to the National

Trails System in 1987 to commemorate the victims.

The term Trail of Tears originally referred to the forced expulsion of the Cherokee and the resettlement of the Choctaw, covered by American legislation. The Cherokee referred to the expulsion as Nunna daul Tsuny (Cherokee for 'The Way We Wept'), which was translated into English as the Trail of Tears and thus became popular. Among the Choctaw, the term refers to a description of their resettlement quoted in the Arkansas Gazette in November 1831, which was described by one of the important chiefs, probably Thomas Harkins or Nitikechi, as "[...] trail of death and tears". of death and tears'). Other newspapers took up this expression in a shortened form as the Trail of Tears and spread it. The term was gradually adopted for the other Southeast Indian nations displaced under the Indian Removal Act, and is now used to describe the overall circumstances of the Southeastern nations' displacement. Occasionally the expression is used to describe violent or costly expulsions or resettlement of other Native American peoples, for example for the 1860 conducted 'Long March' (English: The Long Walk) of the Navajos native to the Southwest of the United States.

Indian settlement areas in the 18th century

In the second half of

the 18th century, the settlement areas of the Indians, which originally

encompassed large parts of the southeastern United States, had shrunk

significantly, mainly as a result of treaties and military conflicts

with the settlers who had come from Europe. Initially, the Indians

remaining in the restricted areas was in the interest of the colonial

powers, for whom the tribal areas were also important as buffer zones

between the various spheres of influence. In particular, the habitat of

the Cherokee and the Muskogee in the mountainous regions of the states

of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee separated the

French, Spanish and British areas of interest from each other.

The Seminoles in sparsely populated central Florida had already been

decimated by the First Seminole War around 1800 and were influenced by

the settlers of the Spanish Florida colony, while the Choctaw and

Chickasaw inhabited fertile land in Alabama and Mississippi south of the

Mason-Dixon line and separated French Louisiana from the Thirteen

Colonies of British colonial power. A lack of interest on the part of

the white settlers saved the areas from further downsizing up to this

point; the settlement areas of the Indians were largely treated as

autonomous states.

With the invention of the gin machine, a ginning machine for cotton, which made it possible for slaves to be used effectively on plantations and thus for the cultivation of cotton on a large scale, the need of the white settlers for further and larger cultivation areas in the southeast grew. The region known as the Black Belt was of particular economic interest. This is an area of black soil suitable for cotton growing that stretches from North Carolina to Louisiana. The boom in the southern states enabled the Native American nations living in this region to increase in prosperity. The fact that the five nations had a long tradition of slave ownership was beneficial for economic development. The slaves were mostly prisoners of war or abducted from other tribes of Indigenous, Afro-American or white descent. Unlike the slavery of the white settlers, the Indian slaves were understood as part of the family and led a largely self-determined life. However, they owed their owners part of their labor power, which had a significant impact on the economic success of Indian agriculture. At the same time, the incipient hunger for land, the appearance of land speculators and the establishment of large plantations threatened the settlement areas of the south-eastern Indian peoples. Partly under pressure from the American government, there were further assignment agreements and land purchases by white settlers. This resulted in a further reduction of the tribal areas.

The pressure exerted on the tribes by the white settlers' hunger for

land increased considerably and permanently changed their way of life

and culture. With the increasing interest of the white settlers in the

region, the spread of the Christian faith among the Indian nations

began, which was accelerated above all by the appearance of the Moravian

Church around 1800. In addition to the proselytizing, the reduction of

the tribal areas also changed the way of life of the affected peoples,

for example the traditional settlement pattern of the Cherokee changed

to a form similar to the European settlement type with individual

cultivation. The economic boom in the South made it possible for a

wealthy class of plantation owners to establish themselves in the

nations. As the well-documented case of the Cherokee tribal leader John

Ross shows, these had a role model function for many of their tribal

members. The nations developed a political system similar to that of the

American-European government and judiciary, built schools, and

increasingly adapted to the lifestyles of their white neighbors. During

this phase, the Cherokee developed their own written language and

published the first newspaper in English and Cherokee.

On the one

hand, this adjustment came about under pressure from the American

government, according to which the assimilation and acculturation of the

Indians should serve as a measure to protect the indigenous population,

to avoid military conflicts and, in particular, to promote trade. On the

other hand, some tribal leaders hoped to become part of the social

fabric of the United States and thereby protect themselves from further

expulsion and dispossession of the tribal lands. The high degree of

acculturation of the Native American peoples from the point of view of

the white people led to the term "Five Civilized Nations", with which

the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muskogee and the Seminole influenced

by the Spanish mission were referred to. However, there was hardly any

recognition as equal members in the society of the white settlers. The

majority of the settlers still viewed the Indians predominantly as a

race inferior to their culture and civilization. Parts of the Indian

population vehemently rejected this adaptation to the foreign culture

and there were massive internal conflicts within the tribes. This was

most evident among the Muskogee, also known as the Creek, whose large

and influential confederacy split in two, eventually leading to civil

war.

The white settlers of the southeastern states began to exert

increasing pressure on their respective governments in the early 19th

century. They asked them to vacate the tribal lands and give the land

and - especially after gold was discovered in Georgia in 1829 - the

mineral resources to the whites.

In order to put the necessary

resettlement of the Indians on a legal basis, the United States Senate

passed the Indian Removal Act on April 24, 1830, which the House of

Representatives approved on May 26 of the same year. On May 28, 1830,

Andrew Jackson signed the law into law, with the support of the southern

states and against the opposition of prominent politicians such as

Theodore Frelinghuysen and Davy Crockett. This authorized him to conduct

negotiations with the tribes and peoples living in federal territory,

which should aim to exchange their lands for areas in the Indian

Territory. These lands, acquired by the United States as part of the

Louisiana Purchase, were not yet part of the United States federal

system at the time and were located in what later became the state of

Oklahoma.

Native American nations reacted differently to the new

legislation, for example, in September 1830, the Choctaw gave up their

lands east of the Mississippi River in exchange for lands west of the

river. The Cherokee tried to strengthen their sovereign rights and take

legal action to defend themselves against the various land cession

treaties. However, as part of the Indian policy and the Indian

resettlement, the lawsuits brought forward by the nation at the Supreme

Court were averted. The Seminoles, on the other hand, refused any

attempt at non-violent resettlement and fought back militarily during

the Second Seminole War.

Contract of Dancing Rabbit Creek

Until 1800, the settlement area

of the Choctaw Nation included large parts of what are now the states of

Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and Louisiana. Through a series of

treaties, the nation was first pushed north of the Mason-Dixon Line

until finally, after the Indian Removal Act was enacted, the Treaty of

Dancing Rabbit Creek traded most of its settlement areas for new areas

in Indian territory. In the treaty signed on September 27, 1830 under

pressure from the American government and effective on February 24,

1831, the Choctaw ceded approximately 45,000 square kilometers of land

(an area comparable to the size of Switzerland) to the federal

government in exchange for approximately 61,000 square kilometers in

what is now known as Switzerland Oklahoma. The treaty, in which the

nation relinquished its sovereignty, did not have the approval of the

people, who had opposed resettlement in previous assemblies and

councils. However, the Indian negotiators Greenwood LeFlore,

Musholatubbee and Nittucachee saw no other way to get at least a remnant

of the original tribal areas for their people. It also made the

remaining Indians in Mississippi citizens of the United States, which

Choctaw leaders hoped would provide better protection for those who

chose not to join the resettlement.

The voluntary resettlement of the Choctaw, estimated at 15,000 to 20,000 members, and their approximately 1,000 Afro-American slaves was planned by the federal government in three groups. The first and largest group comprised 4,000 people whose resettlement on the "water way" (English for "waterway") was scheduled for October 1831. The tasks of the government-appointed "Removal Agents" (English for "resettlement agents"), headed by George Strother Gaines, consisted in planning the routes to the Indian Territory, almost 650 kilometers away, and in procuring wagons, horses and ships as well an appropriate amount of supplies and food for the treks and the first time after arrival in the new settlement area. There was disagreement among these agents about the choice of routes and the organization of the treks. The first group of Choctaws encountered an unclear and confusing situation upon arrival at the assembly points in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee. For example, contrary to the government's assurances, they had to leave their cattle behind and were only to receive replacements for them in Indian Territory. Due to deteriorating weather conditions, the agents decided to transport the Choctaw from Memphis to Indian Territory along a northern route and the tribesmen assembled in Vicksburg along a southern route.

The approximately 2,000 Choctaw gathered in Memphis boarded the provided steamboats with which they were initially to follow the Arkansas River. The heavy rains that began a few days after departure led to flooding, forcing ships to land at Arkansas Post. There was no shelter on land for such a large number of people. Blankets and provisions had not been carried for such a case. The cold rain and subsequent blizzard that left the Choctaw defenseless for several days caused a large proportion of the total deaths within this group. The youngest and oldest were particularly badly affected. The two ships, the "Reindeer" and the "Walter Scott", could not cast off at temperatures well below freezing point, so transporting the Choctaw by water was no longer possible. It wasn't until eight days later that forty government wagons loaded with blankets and supplies were dispatched from Little Rock, Arkansas, to join the group. They picked up the survivors at the Arkansas Post and took them to Fort Smith, from where they moved on to Little Rock. After the first wagons arrived in November 1831, one of the tribal leaders, believed to be Thomas Harkins or Nitikechi, coined the term "Trail of Tears" in a conversation with a reporter from the Arkansas Gazette.

The Choctaw waiting for transport in Vicksburg also boarded two ships. The "Talma" and the "Cleopatra" should bring the group, the Mississippi downstream to the confluence of the Red River and from there the Ouachita River upstream following to Camden in what was then Arkansas Territory. From there, the Choctaw would cover the remaining 100 kilometers to their new territories in covered wagons. However, transport by water had to be interrupted in Monroe, Louisiana, due to machine failure on the "Talma". The Choctaw should wait there to be transported on with the "Cleopatra". The rains and blizzard didn't hit this group nearly as hard as the displaced people on the northern route because of the protective forests surrounding them and the supplies generously shared by the white population with the Choctaw. Shortly thereafter, the southern group reached their stopover at Camden. The preparations made by the agents there were nowhere near what was needed. There were only twelve wagons available and the food rations were insufficient. With the exception of infants and the weakest, the Choctaw were forced to walk the rest of the way. The lack of food was exploited by the farmers along the route. They charged three to four times the usual price for supplies. Various epidemics, including typhus and diphtheria, also held up the trek. It took just under three months to cover the slightly more than 100-kilometer stretch from Camden to the Mountain Fork River.

Although Gaines knew that the resettlement via the southern and shorter route had been smoother and with fewer casualties, in 1832, for reasons unknown, he chose the northern route again. A cholera epidemic broke out in the region as the Choctaw moved toward Vicksburg to be transported west together. The Indians, who also fell victim to this disease, died by the hundreds. The town was largely deserted and there were no supplies to buy. The crews of the ships chartered for the Choctaw had also fled the epidemic. Agent Francis W. Armstrong, assigned to lead a group of about 1,000 Choctaw to Vicksburg, heard about the epidemic. He spontaneously decided to take his group to Memphis first, in order to direct them west via the southern route as quickly as possible. His charges reached Indian territory almost entirely without further incident. Gaines finally managed to hire a crew for at least one of the two ships, the "Brandywine". Around 2,000 people were brought onto the ship. Rains began shortly after this left Vicksburg. It was not possible to continue the journey on the flooded river and the passengers were put ashore at Rock Row about 110 kilometers from their destination Little Rock. There were no provisions available there, there were neither wagons nor horses. Nearly 30 miles (50 km) of the way the Choctaw had to walk was submerged. After four days, the survivors of the march reached Little Rock. There they were provided with medicine, food and clothing and united with the Armstrong group.

The third and final resettlement ordered by the government took place

the following year. Gaines again chose the route via Vicksburg, but

unlike previous years, only around 1,000 Choctaw appeared at the rally

points in October. There was no heavy rainfall this year and the move to

the Indian Territory went as planned.

For the approximately 6,000

Choctaw remaining in Mississippi, conditions deteriorated rapidly. The

promised civil rights proved insufficient to protect the Indians; they

have repeatedly been the target of racially motivated attacks, suffered

persecution and expropriation. In 1836 another group of about 1000

Choctaw decided to move to Indian Territory, 1600 followed a year later

and other smaller groups left Mississippi because of the deteriorating

living conditions in the following years and decades. Around 1910 only

about 1250 Choctaw lived in the original tribal area. The descendants of

the remaining Indians were summarized as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw

Indians in the 1940s under the Indian Reorganization Act and were given

their own reservations in Mississippi.

Estimated Losses

Exact

figures for the displaced Choctaw are not available. Based on around

15,000 resettled people, various estimates come to the conclusion that

around 2,500 people died during the treks carried out by the government

alone. It is not recorded how many of the displaced persons died on the

way to the assembly points, after arriving in Indian territory or during

subsequent resettlement.

By the mid-18th century, the Muskogee, known to settlers as the Creek, were one of the most powerful and influential nations in the South. Confederation of tribes including Coushatta, Yamacraw, Shawnee, and Alabama had at least 40 villages in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Florida, and an estimated fighting force of 1,250 to 6,000 warriors. During the course of the American War of Independence, towards the end of the century, the Confederation broke up as the tribes began to adapt to the lifestyle of the white settlers, which was accepted and implemented in different ways. The "Upper Creek" tribes of the Alabama Valley, who lived further away from the colonies, rejected acculturation. They sided with the British during both the American Revolution and the British-American War. Their former allies, the "Lower Creek" people who settled near the whites on the Chattahoochee, Ocmulgee, and Flint Rivers, were largely neutral or pro-American. The conflict culminated in the "Red Stick War" of 1813-14, a civil war between the anti-American and the conformist factions within the Muskogee. With the victory of the pro-American Muskogee and supportive American militias under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the Traditionalists' resistance was finally broken and they surrendered in August 1814.

Jackson used the post-Civil War situation to force the defeated Upper

Creek and Lower Creek allies, whom he accused of involvement in the

rebellion, to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson in August. In this treaty,

the Muskogee ceded rights to over half their land, some 81,000 square

kilometers (an area the size of Austria), to the United States. This

area became the state of Alabama. Individual Muskogee tribes continued

to sell additional land, although the Muskogee government threatened the

death penalty for selling additional tribal lands. For example, William

McIntosh, along with other Muskogee leaders, signed the Treaty of Indian

Springs on February 12, 1825, ceding much of the remaining territory to

Georgia. Shortly after the treaty was ratified, McIntosh was killed in

May of the same year for what was perceived as a treachery assignment by

a group of Muskogee around Menawa.

The Muskogee Council, led by

Opothleyahola, successfully protested the treaty. A new agreement, the

1826 Treaty of Washington, repealed the previous treaty. The Indian

Springs Treaty is the only ratified treaty between the United States and

a Native American nation that has ever been annulled. However, the

Georgia government refused to recognize the 1826 annulment and continued

the expulsion. Without further interference from the federal government,

the Lower Creek were forcibly evicted from their tribal lands and

migrated in small groups into Indian territory.

The remaining

20,000 or so Upper Creeks in Alabama were further restricted by state

law, such as prohibiting them from establishing sovereign tribal

governments. In another protest note, the Upper Creek asked Jackson, who

has since been elected president, for help. Instead, however, they were

forced into the Treaty of Cusseta, which divided Muskogee territory into

individual parcels. This gave the government and squatters invading

Indian lands access to tribal lands without having to abide by the

federal government's overriding treaties. Increasing pressure was

exerted on the Indian landowners. Looting ensued and farms were set on

fire to evict individual families from their lands. The conflict between

the Muskogee and the white settlers eventually culminated in the Creek

War of 1836. The hostilities between the factions were ended with the

help of the military through the forcible resettlement of the remaining

Muskogee covered by the Indian Removal Act.

After the ratification of the Treaty of Indian Springs in 1825,

smaller, wealthy groups, mostly from McIntosh circles, left their

territories westward. Altogether, about 1,000 to 1,300 Muskogee migrated

with their slaves to settle in the Arkansas Valley, their assigned area

of Indian Territory. In this way they secured preferred and

agriculturally attractive plots of land and created a good starting

point for their individual well-being. Other groups and survivors of the

Red Stick War joined the Seminoles or relatives in areas not yet

affected by the displacement.

Following the Creek War of 1836,

some 2,500 Muskogee were rounded up in Alabama and taken to Montgomery,

Alabama. Among them were several hundred warriors who were tied up and

taken away under heavy guard. The deportation of this group took place

via the Alabama River, which took the Muskogee downstream to the Gulf of

Mexico and then via the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers to Fort Gibson

in Indian Territory. Another 14,000 Muskogee followed this route in 1836

and 1837, who were not allowed to take more than they were carrying.

During the three-month journey in different treks at different times,

they suffered from very hot summers, snowstorms in winter and various

epidemics. An eyewitness described how during one of these

resettlements, a number of Indians froze to death or collapsed from

exhaustion while their relatives were not allowed to bury their dead and

perform the necessary rites.

Another group of around 4000 women,

elders and children were rounded up in camps in March 1837. Their

families had been promised by the government that they would be exempt

from resettlement if their husbands fought on the side of the United

States in the Seminole War. By the time they were able to reach their

families in September, many of the detainees were dying of rampant

diseases due to the conditions in the camps. The survivors also followed

the route via New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico; 311 deportees died in

the accident of one of the unseaworthy ships that they were

transporting. Most of the displaced people settled in the area around

modern-day Okmulgee, Oklahoma. After a period of strained relations

between the Upper and Lower Creeks in the new territory, the alliance

was renewed and the sovereign Muskogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma came

into existence.

A few families remained in Alabama, their

descendants today form the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, which was the

only Indian tribe in Alabama to receive state recognition. They live

mostly on the Poarch Creek Reservation in Escambia County.

There are no clearly documented figures regarding the expulsion and the resulting losses of the individual tribes of the Confederacy. It is not known how many of the Muskogee who originally lived in the southeast were actually expelled, only the numbers recorded by the Indian agents as part of the state resettlement are secure. According to a statement by the United States officer in charge, published in the Arkansas Gazette on January 17, 1838, the entire tribe of 21,000 people was relocated with little or no trouble. Immediately after the resettlement, at least 3,500 people died from diseases known as “pulmonary fever”. It is unclear how many Muskogee bowed to pressure from the settlers or the states and made their way in small family groups to relatives in the Florida swamps or in Indian Territory. It is also not known how many Indians died in the camps or in the military conflicts before the trek began. Anthropologist Russell Thornton assumes, based on detailed research, that about 50 percent of the people were destroyed by the direct and indirect consequences of the expulsion.

The Chickasaw, a numerically small people with about 5000 tribesmen

and 1200 slaves, settled in the states of Mississippi, Alabama and

Tennessee. After the Indian Removal Act was passed, they recognized the

hopelessness of the situation early on and decided to resettle

voluntarily in order to achieve the best possible starting point for the

well-being of their nation. After a first land cession treaty, the

Treaty of Old Town of 1818, the Chickasaw council signed the Treaty of

Franklin in 1830. This agreed to the exchange of appropriate lands to

the west for the original Chickasaw lands. The agreement was not

ratified by the United States Congress because the tribe could not be

offered a corresponding area in Indian Territory. First Chickasaw

expeditions were sent west to prepare for resettlement.

Another

treaty, initially not ratified, was negotiated with the Treaty of

Pontotoc in 1832, which regulated the sale of the approximately 26,000

square kilometer Chickasaw areas for three million dollars (the area

corresponds to the size of Sicily). In 1834, another agreement followed

in the Treaty of Washington, with which the previous treaty came into

effect, although no new areas in Indian Territory were available for the

Chickasaw.

After several expeditions between 1832 and 1837, repeated negotiations failed with the Choctaw, in whose government-allocated section of Indian territory was the Chickasaw's preferred settlement area. Despite their strained relations, the Chickasaw and Choctaw signed the Treaty of Doaksville under pressure from the government, which was trying to expedite the resettlement. In the agreement signed on January 17, 1837, the Chickasaw received the right to settle in the west of the Choctaw region, present-day southwest Oklahoma, for a payment of $530,000. This thwarted the Chickasaw's original plans to buy the land to build a sovereign nation. They received the area only on loan, in addition they were allowed to represent their interests in the Choctaw Council.

Already at the beginning of the looming resettlement initiated by the

government, smaller family groups, especially those from the wealthy

class, moved into the Indian territory and thus secured individual areas

in preferred locations early on. The government-sponsored resettlement

of 3,001 tribesmen and slaves began in the summer of 1837. Under the

direction of A.M.M. Upshaw and John M. Millard, the Chickasaw were

brought to Memphis on July 4, 1837. From there they were to move west

along the routes already used by the Choctaw and Muskogee. Unlike the

previous resettlement, the Chickasaw resettlement was planned with much

more care. Adequate supplies and shelter were available along the route.

The Chickasaw were allowed to use cattle as well as their own ponies and

carts to transport their belongings. Some of the clans chose their own

groups to move into Indian territory without government officials

overseeing them, paying for their relocation from a fund provided by the

tribal government. These self-organized and funded treks cost the nation

around $100,000, with the Chickasaw expecting government payments to

arrive soon.

Contrary to the Chickasaw Council's plan for

nation-building in the West, many of the resettled tribesmen settled

near existing Choctaw villages. As a result, the people lost their

independent identity and merged into the Choctaw nation. Only in 1854,

and after paying further sums to the Choctaw, did the Chickasaw succeed

in giving themselves their own constitution again. The descendants of

some unrelocated Chickasaw, mostly widows and orphans whose resettlement

was unfunded, form the Chaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People of South

Carolina tribe recognized by South Carolina in 2005.

The Chickasaw's losses during the various treks were relatively small due to the good preparation and the funds available. However, at the beginning of the resettlement, a smallpox epidemic was rampant among the population, and after resettlement there were repeated conflicts with the indigenous peoples who were already living in Indian territory. Altogether about 500 to 600 Chickasaw died as a result of the resettlement and its consequences.

The Cherokee settled in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. The tribes, which were highly adapted to the way of life of the whites, were pushed back by the enormous population growth of white settlers until about 1820, but were able to keep their tribal areas and reservations guaranteed by treaties. However, after the first gold discoveries in 1829 in Dahlonega, Georgia, which started the first gold rush in the United States, the attitude of the Georgian government towards the indigenous people who settled in the area changed. The government enacted laws that stripped the Cherokee of various rights, including mineral rights to their own land. This was done for a variety of reasons, including the official claim that Native Americans were unable to manage their lands effectively and that whites could make better use of them. Subsequent investigations have shown that the Cherokee were in an economic upswing at this time and usefully adapted and used the agricultural techniques that had come from Europe.

The Cherokee tried to use legal means to improve their situation and

to prohibit the states from encroaching on the settlement area and to

protect their individual rights. They approached the United States

Supreme Court in June 1830, under the direction of John Ross, a

well-respected Cherokee chief, with the case of Cherokee Nation v.

Georgia. The Cherokee were supported by a number of congressmen,

including Davy Crockett, Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen, at

whose suggestion William Wirt took over the legal representation of the

case. Wirt sought the repeal of all laws enacted by Georgia that

restricted the rights of the sovereign Cherokee nation. However, the

Supreme Court dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that the Indians were

not an independent state, but a "domestic dependent nation" (English for

a native and dependent nation), which as such could not sue for any

rights. However, the Supreme Court has indicated that it will accept and

rule on Indian behalf any additional cases that would be referred for

appeal by a state court.

As a result of this rejection, the

Cherokee attempted to assert their rights through a civil suit. In 1832,

as announced, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee in

Worcester v. Georgia. The ruling, presented by Chief Justice John

Marshall, stated that a state has no right to intervene in the internal

affairs of Native Americans or to dispose of their territory. However,

the verdict came too late, the Indian Removal Act had already come into

effect and was implemented by Jackson in defiance of the judge's

decision. These two decisions continue to influence United States

government policy toward Native Americans to this day.

In view of the external threats to the nation, which saw itself as

sovereign, internal political differences arose over the question of

resettlement. John Ross, behind whom the far greater part of the people

stood with around 17,000 Cherokee, argued against resettlement and any

voluntarily signed agreement that favored such a move. In his view, the

Cherokee were spiritually and culturally inextricably linked to the land

of their ancestors, and survival of the people was only conceivable

there. This position was opposed to the "Treaty Party" around Major

Ridge, which was supported by about 500 tribal members and campaigned

for voluntary resettlement. Their representatives understood the nation

as a social grouping of people whose survival was not secured by the

country but by their existence as a people. They saw this security,

which was also influenced by economic factors, in the voluntary

resettlement in Indian territory.

Members of the Treaty Party,

including Major Ridge and his son John Ridge, signed the Treaty of New

Echota on December 29, 1835, against popular opposition. In this treaty,

the cession of all Cherokee territories east of the Mississippi for $5

million and the allocation of new settlement areas in Indian Territory

were agreed. John Ross wrote a note of protest which he personally took

to Washington, D.C., where he made it clear that neither the nation's

elected leaders nor the broad majority of the people supported the

treaty. Although prominent advocates supported him in Congress and Ross

presented a list of 15,000 signatures opposing the treaty, the agreement

was ratified on May 23, 1836 by a single vote. This made the forced

resettlement of the Cherokee legal. May 23, 1838 was decided as the date

for the resettlement. Even as Ross was presenting his views to Congress

and fighting to preserve the eastern tribal lands for the Cherokee,

members and supporters of the Treaty Party and Major Ridge's family were

moving west.

After ratification of the Treaty of New Echota, the military, with the help of volunteers, began building several forts surrounded by stockades in the south. These prisons, also known in the literature as concentration camps, were intended to house the Cherokee pending their transport to Indian territory; they were only poorly equipped with shelter and provisions. Many of the soldiers and several officers sympathized with the Cherokee and refused to be involved in the deportation. After several rejected appeals, General Winfield Scott finally took on the task of rounding up the Cherokee with the help of 7,000 troops sent from the North. The Cherokee, who made no move to prepare for the move, were ordered by force of arms beginning May 17, 1838 to move to the camps at Gunter's Landing, Ross's Landing, and Hiwassee Agency or, for example, Forts Lindsey, Scott, Montgomery, Butler in North Carolina, Gilmer, Coosawatee, Talking-Rock in Georgia, Cass in Tennessee or Turkeytown in Alabama. Sometimes the Indians only had an hour to pack their belongings. After ten days, known as the "Cherokee Round-ups," the Cherokee had mostly been taken to the camps. The deportees' horses and cattle were confiscated and sold by Indian agents or soldiers. Some families were torn apart by the round-ups and could not be reunited even after the resettlement. Some of the Cherokee, around 1000 to 1100 people, managed to flee and hide in the inaccessible mountain regions of the Appalachian Mountains or to find refuge in the country, especially Scottish settlers. Their descendants form the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians today.

Around 13,000 interned Cherokee spent the summer in the camps.

Disease was rampant, and white traders smuggled alcohol into the forts,

further aggravating the desolate situation. Some historians assume that

more Cherokee died during this phase of resettlement than on the way to

the new settlement areas. Upon Ross' return from Washington, he

persuaded officials to place the resettlement of the Cherokee in the

hands of the tribal government. He planned the resettlement in 13 groups

of 1000 people each. With this decision, Ross avoided hauling away the

Cherokee in a single large trek that would have been difficult to

service. He thus prevented additional losses that would have been

expected from undersupply and disease. The groups left the camps during

the fall of 1838, the last trek led by John Drew leaving the east on

December 5, 1838.

The conditions under which the resettlement,

dubbed the "March of a Thousand Miles" by the Cherokee, began were

catastrophic. The Cherokee refused to leave the camps and their homes.

They were forced to move by force of arms and beatings. They were poorly

prepared for the resettlement due to the round-ups and in poor health

due to the long stay in the camp. The loading of a small part of the

Cherokee on ships and the departure of others on foot further separated

families. The two main Cherokee routes together represent the

northernmost resettlement stretches of the Indian resettlement routes.

On both routes, on the one hand on the march through Tennessee,

Kentucky, through southern Illinois and Missouri, on the other hand on

the waterway over the rivers Tennessee, Ohio, Arkansas and Mississippi,

the Cherokee suffered from winter storms with temperatures well below

freezing. In addition to deaths from freezing, malnutrition caused by

very short rations, accidents and exhaustion, other tribe members died

from diseases such as measles, cholera, whooping cough and dysentery.

This particularly affected the children and the elders of the people,

for whom the up to six-month walk to the Indian Territory, almost 2000

kilometers away, was hardly manageable. Accompanying soldiers were

shocked by the brutality of the march, for example a Georgia militia

volunteer, despite his later experience in the American Civil War,

retrospectively described the deportation as "...the most gruesome work

I have ever seen." The Cherokee refer to the resettlement as " Nunna

daul Tsuny" (Cherokee for The Way We Cried). As the most costly of the

deportations, it became the epitome of the expulsion of Indian nations

from the southeast.

The Cherokee struggled to self-record their losses throughout the resettlement. However, in many cases they did not succeed in keeping up with developments, ritual burials and farewell ceremonies were only possible in a few cases. Subsequent investigations and the evaluation of the various government transport lists indicate the number of victims at least 4,000 people, with the number likely to be around 8,000 according to more recent research. This estimate also takes into account the Cherokee who died in the camps. Other deaths occurred upon arrival in Indian Territory. These include deaths caused by conflict with other races or previously resettled Cherokee, and the Council's execution of male Ridge family members and other signers of the Treaty of New Echota.

The heterogeneous group of Seminoles lived on a reservation in

central Florida after the sale of Spanish Florida to the United States

in 1823. In addition to older tribes of the region such as the

Apalachicola or the Timucua, it was also made up of various Muskogee

family clans and refugees. Much of the nation was made up of

African-American or mixed-race slaves, or freed or escaped Northern

ex-slaves. The swampy interior of Florida was not suitable for feeding

the people living on the reservation, which is why they hunted and

procured supplies primarily in the north of their settlement area. The

settlers who lived there viewed the invading Seminoles with great

suspicion. This was particularly due to the close connection between the

Indians and the African Americans who lived with them. Although the

white settlers had no economic interest in the reservation area, they

pushed for a resettlement of the Seminoles around 1830.

Famine,

crop failures and the lack of economic prospects convinced the Seminole

leadership to enter into treaty negotiations with the government. The

United States wanted the Seminoles to join the Muskogee in Indian

Territory and return all runaway slaves to their owners. The Treaty of

Payne's Landing of May 9, 1832 finally gave up the reservation against

new areas in Indian Territory. A prerequisite for ratification was that

suitable areas for the Seminoles could be found in Indian Territory. To

find such areas, a delegation of Indians traveled west. After the end of

the expedition in the spring of 1833, the seven participants were forced

to sign the Treaty of Fort Gibson while they were still in Indian

territory. This confirmed that the Seminoles had found suitable land to

the west and enabled Congress to ratify the Treaty of Payne's Landing in

April 1834. This was done without further information or consultation

with the Seminoles in Florida. The deportation was to be carried out by

1835.

The various factions within the Seminoles refused to heed the request to resettle. In their view, they were not adequately involved in the decision. Added to this were the concerns of having to join a people who were foreign to them. The fear of influential African American groups and the Black Seminoles also influenced this refusal. The African Americans, who formed an integral part of the tribes, feared being enslaved for the first time or again. Seminole resistance culminated in the Second Seminole War at the time of the planned resettlement in January 1836. The war dragged on until the death of Osceola, the main Seminole leader, in 1842. This war is considered the longest and costliest Indian War in United States history. It cost the lives of 1,500 American soldiers and an unknown number of white and Native American civilians, and cost over $30 million. Seminoles captured during the war were deported to Indian Territory.

After the end of the Second Seminole War, around 4,000 Seminoles and their allies of African American descent were tracked down, hunted down and rounded up in the swamps with the help of the military. They were interned in two camps in the Tampa, Florida area. There, the women and children suffered particularly badly; there were hardly any rations or clothes for them. Whites, with the help of the military commanders, gained access to the camps and tried to extract runaway slaves and Afro-American Indians from their families and convert them into white slavery, which in a number of cases was successful. The Seminoles were gradually shipped across the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans by steamboat in smaller groups. There they followed the waterway across the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers to Fort Gibson in the Muskogee area of Indian Territory. However, they did not merge into the Muskogee nation, but formed the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. This nation also includes two tribes of Black Seminole, who today call themselves "Freedmen" (English for freed people). A few hundred Seminoles hid in the Everglades to avoid deportation. They did not submit to the American government during the Third Seminole War (1855-1858). As a result of this war, another 200 prisoners were deported. The descendants of the Seminoles who remained in Florida today form both the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida.

Little is known about the losses of the Seminole, whose resettlement and expulsion lasted from 1820 to about 1850. In total, an estimated 2,833 of the almost 5,000 Indians living in Florida were resettled, which means they arrived in Indian territory. How many died in the camps or on the way west, or fell into white slavery, is unknown. The number of Seminoles killed in the Second Seminole War is also not documented; the surviving group, which settled in the Florida swamps and permanently evaded resettlement, numbered 250 to 500 people.

Living conditions in the reservations

The tribes, traumatized by

the forced resettlement and the numerous losses, encountered a world

that was largely foreign to them in the Indian territory. The

environmental conditions in the rather barren Indian territory differed

significantly from the very fertile and infrastructurally well-developed

settlement areas from which the peoples came. The "civilized nations,"

heavily adapted to the way of life of the white man, lived in fear of

what they saw as "savage tribes," as they called the original

inhabitants of the land. There were repeated conflicts and battles with

the nomadic Plains Indians, who included the Sioux, Cheyenne, Comanche

and Blackfoot. Their settlement areas and habitat were restricted by the

arrival of around 100,000 Indians from the southeast. This initially led

to a crowded settlement of the deportees around the larger towns and

forts, through which the newcomers hoped protection from the Plains

Indians, but also to increasing problems among the various tribes. The

situation was exacerbated by the lack of arms deliveries, which the

newly settled tribes had been promised by the United States for

self-defense.

In addition to the losses caused by these

hostilities and conflicts among the resettled and sometimes hostile

peoples, there were further deaths, numbering in the hundreds, in the

first phase of the resettlement. This was caused on the one hand by

diseases that grew into epidemics among the exhausted people, on the

other hand by the poor timing of the resettlement. The late arrival

prevented timely sowing, which resulted in hunger and crop failures. The

government's food supplies, which were supposed to absorb these

shortages, either failed to materialize or were insufficient to feed the

Indians.

The government's demands for the union of the Seminole

with the Muskogee and the Chickasaw with the Choctaw were vehemently

opposed by these peoples. The amalgamation of the settlement areas

proved to be unsustainable and led to further treaties that enabled a

clear mutual demarcation and separation of the nations. Further

resettlement within the Indian territory, which particularly affected

the Seminoles, led to the pacification of the conflict. In the peaceful

phase that followed after 1856, the peoples recovered economically,

albeit very slowly in some cases. Although the economic situation of the

Indians remained significantly worse than before the resettlement, this

served as confirmation for the supporters of the Indian Removal Act that

the losses suffered by the Indians had ultimately ended well and that

the expulsions had been positive for the Indians.

The personal losses that each of the deported families suffered,

literally, and the cultural and spiritual uprooting led to an attitude

that was commonly described as apathy. This prevented many of the

resettled people from gaining a foothold in the initial phase and lasted

up to thirty years in some tribal associations. Only then did those

affected begin to break free from their dependence on government food

supplies and payments and to rebuild their nations in the West.

In some peoples, tensions arose over the issue of the governmental and

judicial system between those who had voluntarily resettled in the early

phase of the displacement, the “old settlers”, and those who were later

deported. Contrary to the forecasts of the white opponents of the Indian

Removal Act, however, there was no dissolution and decay; on the

contrary, all peoples succeeded in regaining their sovereignty and

establishing a political system by the middle of the 19th century.

Similar to the individual legal systems, this was modeled on the forms

of government already used in the East and influenced by American and

European influences. Towards the end of the 19th century, parts of the

territory promised to the Indians "forever" were released for settlement

by white settlers during the "Oklahoma Land Run". In order to prevent

the further restriction of their settlement areas and a new expulsion,

the five civilized nations tried to form a federal state. The state

should be named Sequoyah in honor of the inventor of the written

Cherokee language. After the bid for state recognition was rejected,

Indian Territory merged with neighboring Oklahoma Territory. Together

they founded the state of Oklahoma.

By the time of the

resettlement, the peoples had adopted the European understanding of land

as an economic good, a fundamental change in their attitude towards the

traditional religious-spiritual respect for the land. In this dichotomy,

they lived mostly on family-owned farms, growing a variety of crops and

vegetables, and largely abandoned hunting in favor of keeping

domesticated animals. The economic progress of the individual families

was primarily determined by the location and quality of the settlement

areas. For some, for example, the construction of the railroad through

Oklahoma brought additional income from the sale of lumber, while others

gained wealth from mining for coal and iron ore. Other influencing

factors were the attitude towards slavery, which was used for the

effective management of the farms, and the dependency on the United

States, as well as the amount of support it paid to the Indians. The

majority of the Indians, however, arrived in Indian Territory completely

penniless because of the circumstances of their deportation. It was not

until well into the mid-20th century that they recovered economically

and were able to support themselves on their reservations, such as

through tourism and casinos, without assistance from the United States.

The peoples of the Southeast saw themselves in close connection with

the land on which they lived. It was an integral part of their spiritual

and cultural identity. When they were expelled, they initially lost this

connection to their environment. This was reinforced, for example, by

the ban on reburying the bones of their ancestors when they were

resettled. Stones that were secretly carried along became the greatest

possession of the resettled people and represented the ideal connection

to their lost homeland. During the phase of resettlement and

resettlement in Indian territory, the peoples were accompanied very

intensively by Christian missionaries. Daily Bible readings, church

services and Christian songs partially supplanted the Indian ceremonies

and became part of the indigenous culture. For example, among the

Cherokee, this is evident in the people's unofficial national anthem,

"Amazing Grace," which does not come from their original culture but was

introduced by the missionaries during the Trail of Tears. Although

almost fully Christianized, the peoples managed to preserve key rites

and ceremonies, such as the Choctaw and Muskogee "Green Corn Dance," and

establish new ceremonial and burial sites that were integrated into

their newfound Christian identities.

In order to promote further

acculturation in the spirit of the whites, the Indians were forbidden by

various state regulations to cultivate their culture. These included

being banned from speaking their languages and forcing children into

state schools to assimilate white culture at an early age. Traditionally

anchored concepts such as the transmission of Indian knowledge about the

use of medicinal plants, traditional craftsmanship, but also the

matrilineal structure of many tribes and the oral transmission of Indian

history were made more difficult, and in some cases even partially or

completely suppressed. Despite these measures, the Indian culture could

not be permanently suppressed. The tribes preserved their cultural and

spiritual origins and undertook a variety of efforts, for example to

preserve their languages and ceremonies or to re-establish them at a

later date.

Research

Late research in the 1970s in the work of Grant Foreman

initially focused on fact gathering. For example, the relevant

government documents were evaluated, including loading and transport

data; the first verified figures for deaths come from this research.

This was followed by important insights into the political and social

factors, both within the peoples and in the course of the federal

government's Indian policy. These factors continue to be the subject of

research into the tear pathway. Towards the end of the 1980s, Russell

Thornton reassessed the events in terms of the number of victims and the

Indian persecution[78], after which he concentrated his investigations

in particular on the Cherokee and their population development. There is

now increasing scrutiny of the cultural implications of resettlement,

including assimilation, rediscovery of spiritual identity, and achieving

a balance between Native American heritage and white influences. The

historian Clara Sue Kidwell assesses the research on this topic as

ongoing. Part of the archaeological research, in many cases co-funded by

members of the tribes, involves searching for the unmarked graves along

the Trail of Tears. Universities, including Southern Illinois University

Carbondale, work with both the Indian nations and the National Park

Service. Other projects supported by the National Park Service deal with

the investigation and preservation of individual historical sites,

certain sections of road or the documentation of the connections as well

as their preparation for museums, schools and other public institutions.

Extensive archives are maintained for research and documentation

purposes, such as the Native American Press Archive at the Sequoyah

Research Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

The displaced peoples initially preserved the history of resettlement

and migration into Indian territory orally and passed it on to their

descendants as part of their individual tribal history. In individual

cases, the stories were still recorded in writing by contemporary

witnesses, but many Indians rejected the use of written language. Most

of the novels, songs and stories dealing with the resettlement and

coming to terms with personal fates therefore come from descendants of

the survivors. One of the best-known oral traditions is that of the

Cherokee rose, a species of rose common to the Southeast that has been

designated Georgia's state flower. According to legend, every tear that

was cried during the expulsion became such a rose; its white color

refers to the mourning of the mothers, the seven leaves on the stem are

reminiscent of the seven displaced Cherokee tribes and the yellow

inflorescence symbolizes the gold that cost the Cherokee their homeland.

While the processing of the path of tears within white culture and

art plays no role compared to the myth of the "Wild West", the artistic

examination of the loss of the original settlement areas within

indigenous art is of great importance. In addition to pictures and

drawings, new media such as films, videos and the Internet are also used

by the descendants of the resettled Indians, known as "survivors", for

processing. The personal confrontation with the individual family past

often takes place through hikes or trips, similar to pilgrimages, along

the resettlement routes.

attitude of the government

In 2000,

the outgoing director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs expressed his

regret and blamed his agency for the injustice suffered, but the US

government distanced itself from those statements. Another push for an

official statement from the United States was made in 2004 by Senator

Sam Brownback. He introduced Joint Resolution 37 to the Senate, which

calls for the issue of an official apology for past Indian policies.

Until 2009, the American government had not publicly apologized for

its more than two centuries-long policy on Native Americans, although

corresponding debates had begun. In 2009, compensation agreements were

reached between the government and tribal representatives for the

economic use of the reservations since 1896. On December 19, 2009,

President Barack Obama finally signed a declaration without any

significant media attention, in which he “on behalf of the people of the

United States to all Native Americans (Native peoples) for the many

incidents of violence, abuse and neglect inflicted on Native peoples by

citizens of the United States."

Various sites relevant to the

resettlement have now been designated as National Historic Sites and two

Trail of Tears routes have been included in the National Trails System.

In 1987, to commemorate the events and losses associated with the displacement and resettlement of the Southeastern peoples, the United States Congress approved the establishment of the "Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail" as part of the National Trails System and its management by the National Park Service. The trail extends over around 3540 kilometers and leads through nine states. Two Cherokee resettlement routes were chosen, one following the waterway, the other following the land route west. Various memorials, state parks and sites of special historical interest are located along these two routes. These include, for example, the "Junaluska Memorial and Museum", an important burial site and memorial to the seven displaced Cherokee tribes in Robbinsville (North Carolina), "The Hermitage" not far from Nashville (Tennessee), the former home of Andrew Jackson, in which exhibitions on Indian politics be shown, and the "North Little Rock Riverfront Park" in North Little Rock (Arkansas), where a number of resettlement routes crossed. Other points of interest along the trail include the New Echota State Historic Site in Calhoun, Georgia, the Trail of Tears State Park near Jackson, Missouri, and the Fort Gibson Military Site in Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, a sculpture by a Danish sculptor was erected in 2016. In addition to the parks and memorials maintained by state organizations, there are various privately owned museums, monuments and historical buildings along the trail that deal with the history of the Indian expulsion and the resettled nations. The inclusion of further sections of the route in the official course of the "Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail" is planned.

The pop song Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian), written by John D. Loudermilk and hit the European and American charts in two different cover versions in the 1970s, refers to the historical process of the Cherokee deportation . The theme is also featured in the songs "Cherokee" by Europe and "Creek Mary's Blood" by Nightwish and "Trail of Tears" by W.A.S.P. and taken up in Jacques Coursil's Trails of Tears album.