Location: Healdsburg, CA Map

Constructed: 1812

Fees and permits: A day-use vehicle permit costs $8.

Fort Ross is a historic Russian fortress that was constructed in future state of California to protected South borders of the spreading Russian Empire against Spanish Empire to the South. Fort Ross was found here as a fortress post for the Russian empire in 1812. Fort Ross was intended to safeguard the possessions of the Russian tsars in the New World from competing Spaniards to the south. Napoleon's betrayal of the Spanish kings allowed cooperation between the two countries. Otter hunting and agricultural ventures were chief tasks of the new settlers. However its role was fairly brief and the fort along with surrounding lands was sold in 1841 following decimation of local fauna by international over hunting.

Fort Ross (probably derived from Russian Россия,

transcription Rossija, for Russia) was a branch of the

Russian-American trading company in California from 1812 to 1841. It

is located on the Pacific coast in what is now Sonoma County, about

90 miles northwest of San Francisco.

As the southernmost

fortified outpost of Russian America, Fort Ross served both as a

base for fur hunting and to supply Russian trading posts in Alaska

with food.

With declining sea otter populations and

unsuccessful agricultural exploitation, Fort Ross became

increasingly uneconomical from the 1830s onwards. At the same time,

the Russo-American Company faced increasing difficulties in

maintaining its territorial claims against mounting pressure from

Mexican and American settlers.

In 1841, Fort Ross was finally

sold by the Russian-American Company's agent, Dionissi Sarembo, to

Johann August Sutter, who incorporated it into his private colony of

New Helvetia, which was under Mexico's control. After the

Mexican-American War, all of Upper California (Alta California) and

with it Fort Ross fell to the United States in 1848 in the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo.

In 1906 the fort was sold to the State of

California and in 1916 and 1925 portions of the buildings damaged by

decay and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake were reconstructed. In

1948 the only completely preserved building was restored, and after

a fire in 1970 the Orthodox chapel was subsequently restored. The

entire complex had already been recognized as a National Historic

Landmark a decade earlier. The reconstruction of a two-story

warehouse was completed in 2012.

Today the fort is used for

tourism and serves as a reminder of America's Russian colonial

history. Fort Ross has been listed as a state park in California

since 1962.

There are motels located about a half mile drive

further up Highway 1. You can also just camp in your car, although

it is not recommended that you do this in the Fort Ross parking lot.

Camping

Basic camping facilities are available to the south

about a 2-min drive at The Reef Campground. (Pit toilets, camp

sites, dirt road, pay phone. Cell phones don't work here.) Open most

of the year. Other camp grounds are to the north, 10-20 miles.

Back country

The coastal mountains that tower over the fort

have some great hiking trails. Just ask at the visitors center.

there are also hiking trails along the bluffs to the north and south

of the fort.

Background: Russia's expansion into America

In

1639, while the Thirty Years' War was still going on in Western Europe,

Russian hunters and soldiers advanced to the shores of the Pacific

Ocean. In 1648, the Cossack Semyon Ivanovich Dezhnev, together with

Fedot Popov and Gerasim Ankudinov, sailed through the straits between

Asia and America, disproving the notion that there was a land connection

between Asia and America. But it was not until the Russian advance to

Alaska in the course of the Second Kamchatka Expedition in 1741 under

Bering and Chirikov and the associated discovery of its economic

potential that the Russian expansion to America began. Fueled by the

profits of seal and sea otter hunting, more than 40 Russian merchants

and trading companies outfitted expeditions to the Aleutian Islands and

mainland Alaska from 1745 through the late 18th century. In the early

19th century, an average of around 62,000 furskins entered the Russian

trade from North American branches each year.

This rapid growth

of the fur trade necessitated the establishment of permanent bases for

hunting and storing the furs. In 1784, Russian navigator and

entrepreneur Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov established the first permanent

trading post on Kodiak Island off the south coast of Alaska. At his

death in 1795, Shelikhov's company dominated Russian trade with America.

Two years later, his widow Natalia combined the trading company with a

business partner and a competitor to form the United American Company.

After another two years, the Russian-American Company was formed in 1799

by ukase of Tsar Paul I from the United American Company. This received

– always for twenty years – the trade monopoly in Russian America and

thus the right to use the Aleutian Islands, the Kuril Islands and the

territories on the North American mainland down to the 55th parallel,

the assumed landing point of Chirikov in 1741. About the shareholders

included members of the royal family, the Russian nobility and leading

officials of the Russian Empire.

In 1790 Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov had recruited the

fur trader Alexander Andreyevich Baranov as one of two area managers of

his company and sent him to Alaska. Baranov proved so successful in

running the fur business that he was appointed first head of the

Russian-American Company when it was founded in 1799. With the help of

his assistant Ivan Aleksandrovich Kuskov, Baranov later managed the

growing business of the trading company from Novo-Arkhangelsk (“New

Arkhangelsk”; today Sitka) and became one of the “main architects of

Russia’s southern expansion”.

On April 18, 1802, Baranov received

secret instructions from the Russian-American Company to expand Russian

territory southward beyond the 55th degree north latitude and to

establish a settlement near the 55th degree north for this purpose. They

wanted to establish facts to use the space created after the Nootka

Sound controversy and establish a recognized boundary between roughly 50

and 55 degrees north at some future point in the future. In 1803 Baranow

entered into a joint venture with the American Captain Joseph O'Cain. He

brought a group of Aleutians under Russian command on his ship to the

coast of present-day San Diego. Baranow and O'Cain shared the profit

from more than 600 sea otter skins.

Another reason for the

Russian push into California was the continuing problems with the food

supply of the Russian bases in Alaska. In the inhospitable climate of

Alaska, the Russian settlers had had only meager success in their

attempts to establish an adequate supply situation. The winter of

1805/06 was the turning point. Supply ships could not regularly call at

Novo-Arkhangelsk because of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars in Europe. The

Russian inhabitants of the colony were malnourished and soon suffered

from the deficiency disease scurvy. The first settlers died.

In

this situation, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, one of the initiators of the

Russian-American Company and Shelikhov's son-in-law, came to

Novo-Arkhangelsk for inspection. In view of the catastrophic conditions

in the settlement, he decided to act quickly. He bought an American ship

anchored in the port of Novo-Arkhangelsk and in the spring of 1806

sailed to Yerba Buena (the precursor of modern-day San Francisco) to

establish trade contacts with the Spaniards and to buy grain.

In

the Presidio, the Spanish military base in San Francisco Bay, Rezanov

lived for a few weeks with the family of Spanish commander José Dario

Argüello and exchanged Russian tools for grain. Argüello assured him of

his support and wrote to Madrid asking for confirmation of

Russian-Spanish trade contacts. On his return to Novo-Arkhangelsk,

Rezanov urged Baranov to use the "uninhabited tract" of California coast

as a Russian base for fur hunting and for supplying food to Alaska.

The founding of the Russian colony

Between 1808 and

1811 Baranov sent his deputy Kuskov on several reconnaissance trips to

California. In today's Bodega Bay, Kuskov built a first temporary

settlement, which he named after Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantsev, the then

Russian Foreign Minister. It was from Rumyantsev that Kuskov explored

the surrounding coastline and in 1811 finally settled on a small bay to

the north as a suitable spot for a Russian colony.

There he met

the Kashaya, a branch of the Pomo. The Kashaya lived along a 30-mile

stretch of coastline stretching from the Gualala River in the north to

Duncan's Point, 4 miles south of the mouth of the Russian River. One of

the central points in the territory of the Kashaya was the village of

Metini, in the immediate vicinity of which Fort Ross was to be built.

The food supply in the habitat of the Kashaya was varied, ranging

from mussels, fish and the marine mammals of the Pacific to deer, elk

and a wide range of smaller animals. The menu was supplemented by nuts,

berries, cereals, tubers and roots. The Kashaya harvested sea salt for

their own consumption and for trade. The Kashaya were particularly

skilled at making baskets. In the oral tradition, the first Russians

appear as undersea people. For them they represented only an episode,

because they disappeared again after three decades. Still, as late as

the late 20th century, elders could describe how the Russians threshed

grain by driving horses across the spread stalks laid out on a prepared

clay, later wooden, floor.

In March 1812, Ivan Kuskov began

building the fort with 25 Russians – many of them craftsmen – and around

80 native Alaskans (mostly referred to by the Russians simply as

“Aleutians”) with the construction of the fort. The Russian craftsmen

followed the traditional model in the construction Wooden building of

Siberia.

On August 30th, the name day of Tsar Alexander I, the

completion of the picket fence was celebrated with a special service. In

the north-west and north-east corners of the palisade, wooden towers

overlooked the area around the fort. Flagpoles bearing the flag of the

Russian-American Company were erected in the center of the fort and on

the edge of the bluff facing the Pacific. Inside the palisades stood

blockhouses for the residents of the fort.

Outside the fence, a

windmill, bakery, orchard, cemetery, and farm buildings were built over

the next five years.

A multiethnic community

The population of the

Russian colony was divided into four groups. Within the fort lived the

more privileged Russian employees of the trading company. Descendants of

Russian men and indigenous women lived—as did lower-ranking Russians—in

a village west of the fort. Stretching toward the Pacific was a small

cluster of simple wooden shacks occupied by Alaskan natives recruited by

the Russians to hunt. The Kashaya lived in a small village northeast of

the stockade and in other villages in the mountains above the fort.

The majority of the colony's Alaskan community was Alutiiq, a people

from southwest Alaska. They came from Prince William Sound Bay, the

Kenai Peninsula and Kodiak Island. Files of the Russian-American Company

as well as archaeological finds show that in addition to the Alutiiq,

Unangan, inhabitants of the eastern Aleutians, also lived in Fort Ross.

Both Alutiiq and Unangan were skilled seal and otter hunters and were

initially used only for hunting marine mammals. In later years they were

also used for every form of heavy work. For example, they worked as

cooper, tanner, carpenter, hunter, fisherman and helped move wood in

areas where horses could not be used. In 1821, Ivan Kuskov asked his

superiors in Novo-Arkhangelsk for a special reward for five of his Aleut

workers who had been engaged in logging for years. The Aleutians, who

had previously only been paid in clothes and shoes, now received an

annual salary of 100 rubles.

Relations between Russians and

Indians were remarkably strained compared to those between other

California aliens and Indians. The Indians employed at Fort Ross were

remunerated with flour, meat and clothing, as well as housing. Many of

the Kashaya learned the Russian language, and a number of Russian

expressions found their way into the Native American language.

The Russians had brought almost exclusively male Alaskan natives to Fort

Ross. The resulting lack of women meant that numerous communities formed

between the Aleutians and the native Kashaya. According to a census

conducted by Ivan Kuskov, the founder of Fort Ross, in 1820, out of 56

Kashaya females, 43 lived with Kodiak Island males. The censuses of the

years 1820 and 1821 show that a total of 28 children were born of these

connections.

Religion was an important aspect of the life of the

Russian inhabitants of the colony. Between 1823 and 1824 the officers

and crew of three Russian ships donated money for the construction of a

chapel. This first Orthodox building south of Alaska is first mentioned

for the year 1828 in the voyage report of the French captain Auguste

Duhaut-Cilly (Voyage autour du Monde. Principalement à la Californie et

aux Iles Sandwich, pendant les années 1826, 1827, 1828, et 1829, Paris

1834–1835) documented in writing. The chapel was used by the settlers

for communal prayer, but was never consecrated as a church (simply

because no priest was permanently assigned to it).

In the summer

of 1836, the missionary and priest Ivan Veniaminov, later canonized as

"Saint Innocent of Alaska," visited Fort Ross. During his five-week

stay, he conducted baptisms, weddings, confessions, funerals, and

services. In his travel journal, Veniaminov put the total number of

people living in Fort Ross at 260, 15 percent of whom were Native

Americans who had converted to the Orthodox faith.

As early as 1816, the sea otter population was

declining due to overhunting. From 1820 at the latest, the

Russian-American Company therefore paid more attention to agriculture

and animal husbandry in Fort Ross. However, hopes that the Russian

settlement in California could ensure the food supply in Alaska were not

to be fulfilled.

The reasons for the agricultural failures were

varied. On the one hand, the usable land in the immediate vicinity of

the settlement was too small and not sufficiently fertile. The fog that

was common around Fort Ross also resulted in grain harvests that fell

short of the company's expectations. In addition, the settlers lacked

sufficient knowledge to manage the soil effectively.

Only the

cultivation of fruit and wine showed early successes. The first peach

tree was planted in 1814. Between 1817 and 1818 vines from Peru and more

peach trees from Monterey were added. When the Russians left in 1841,

the orchard planted in the immediate vicinity of the fort included

apple, peach, cherry, pear and grape vines.

Compared to growing

grain, the Russian settlers achieved greater success with animal

husbandry. Livestock grew to thousands of cattle, horses, donkeys, and

sheep over the years, allowing shiploads of salt beef, wool, tallow,

hides, and butter to be shipped to Alaska. In the colony's final years,

Russian livestock numbered 1,700 cattle, 940 horses, and 900 sheep, all

in "excellent condition," according to a report by Frenchman Eugène

Duflot de Mofras.

The forests surrounding Fort Ross provided rich

material for building ships. In 1817 Alexander Baranov, the chief

administrator of the Russian-American Company, sent a shipbuilder from

Novo-Arkhangelsk to Fort Ross. In the following years three brigs and a

schooner were built under his direction. The ships had a payload of

between 160 and 200 tons and cost between 20,000 and 60,000 rubles.

The travel notes of Kyril Khlebnikov, an employee of the

Russian-American Company, give detailed information about shipbuilding

at Fort Ross. Khlebnikov was in Russian America between 1817 and 1832,

and his journals and notes are among the most important sources on the

Russian colony in California. Khlebnikov's reports tell why shipbuilding

at Fort Ross was eventually abandoned. He repeatedly reports problems

with wood rot that settled in the ship's planking. The fungal

infestation eventually assumed such proportions that the larger ships

could only be used in coastal traffic.

The production of other

goods, on the other hand, was crowned with greater success. In

particular, the tanning of animal skins flourished. A tannery was

established on the banks of the small river Fort Ross Creek, where an

Aleutian tanner produced material for shoes, boots and other leather

goods. Production was so successful that by the late 1820s between 70

and 90 tanned hides could be shipped to Novo-Arkhangelsk annually.

In 1814, the settlers built California's first windmill on a hilltop

near the fort; another mill processed more than 30 bushels of grain a

day. A third mill was powered by human and animal muscle power. A

Kashaya legend has it that one of her wives' hair, which was still worn

long at the time, got caught in the gears and she was killed by the

grinder.

In the field of trade, contacts with the Spaniards

living in the south had existed since Resanov's trip to Yerba Buena.

Although the Spaniards were officially forbidden to trade with

foreigners, the Spaniards nevertheless sold grain, fruit trees, cattle

and horses to the Russians, especially in the early years. As the

Russian colony grew, the artisans at Fort Ross increasingly manufactured

goods for which there was a demand on the Spanish side. Thus, the

Russians sold axes, nails, tires, pots and longboats to the Spaniards in

exchange for grain, salt and other raw materials.

With the end of

the Mexican War of Independence in 1821 came an end to trade

restrictions. As a result, the Russians increasingly competed with the

Americans and British. Upkeep of the Russian port at Bodega Bay

partially offset this. Here the Russo-American Company had built storage

facilities, and their port was open to all foreign flags.

During the period that Fort Ross served as a trading

post for the Russian-American Company, a number of explorers and

explorers came to Upper California.[16] They used the fort as a stopover

on their travels and as a starting point for work on zoology, botany,

geography and ethnology.

In 1818, Russian naval officer Vasily

Mikhailovich Golovnin came to Fort Ross as part of his circumnavigation

of the world. In his memoirs, Golownin provides detailed descriptions of

the Indigenous peoples of Northern California and their culture.

In the early 1830s, the then Chief Administrator of the Russian-American

Company, Ferdinand von Wrangel, promoted scholarly study of the flora

and fauna of Russian America. During a voyage in 1833 he also explored

the possibility of expanding the Russian possessions into the hinterland

of Fort Ross. In this context, Wrangel led the first major

anthropological study of indigenous people in the Russian River region

and the area around modern-day Santa Rosa.

Among later visitors

to Fort Ross was the painter Ilya Voznesensky, who spent a year in

Northern California on behalf of the Imperial Russian Academy of

Sciences. Numerous drawings of the fort and the surrounding region come

from his hand. In 1841, Vosnesensky was among the participants in a

reconnaissance voyage that advanced to the area of present-day

Healdsburg. This included the first ascent of Mount Saint Helena, the

highest point in Sonoma County today. In the course of his travels

inland Voznesensky put on an ethnologically significant collection of

indigenous artefacts, which is now kept in the Museum of Anthropology

and Ethnography in Saint Petersburg.

In 1839 the Russian-American Company decided to

abandon Fort Ross. The decline in sea otter populations since the

mid-1830s made fur hunting uneconomic. The agricultural use of the

colony had not brought the desired success. Attempts to engage in

shipbuilding had failed earlier, and the production of industrial

products could not sufficiently compensate for the deficits.

In

addition, pressure from Mexican and American settlers had increased. In

1836 Ferdinand von Wrangel made one last attempt to improve relations

with the young Republic of Mexico. During a visit to Mexico City, he

campaigned for the recognition of Russian territorial claims in Upper

California, but failed when he demanded that Russia diplomatically

recognize the Republic of Mexico in return.

Finally, in April

1839, the Russian Tsar Nicholas I approved the Russian-American

Company's plan to abandon the Fort Ross base and withdraw from

California. Alexander Rotschew, the last commander of Fort Ross, was

commissioned with the resolution.

Rotchev initially entered into

negotiations with the Canadian Hudson's Bay Company, but they rejected

the offer in 1840. Rotchev then turned to the French military attaché in

Mexico City, Eugène Duflot de Mofras. After a visit to Fort Ross, Duflot

also decided against a purchase. As a result, Rotschev received the

order to ask Mexico for an offer. But the Mexicans also refused - partly

because they considered Fort Ross to be on their territory anyway, and

partly because they hoped that the Russians would withdraw from

California without further intervention.

In late 1841, Rotschew

finally made contact with Johann August Sutter, a Californian landowner

of Swiss descent. Sutter agreed to the purchase for the sum of $30,000,

and on January 1, 1842, the last Russian ship set sail from Bodega Bay

bound for Novo-Arkhangelsk. This ended Russia's involvement in

California after around 30 years.

Second half of the 19th century: agriculture and

animal husbandry

After the departure of the Russian-American Company,

a period began when the lands around Fort Ross were mainly used for

farming and ranching. Until 1843, the fort and its lands were

successively managed by three different administrators on behalf of

Johann August Sutter. The fourth administrator, Wilhelm Benitz of Baden

in Germany, initially worked for Sutter before leasing part of Sutter's

lands in the autumn of 1843 together with his partner Ernest Rufus, who

came from Württemberg. In 1849, Benitz and Rufus added the 17,760-acre

northern portion of the former Russian tenure that had been sold to

Manuel Torres by the Mexican government in 1845. After a few years,

Rufus and Benitz separated; Benitz entered into a new partnership with

Charles Meyer – but the property essentially belonged to Benitz from

then on.

Benitz' company proved to be extremely successful. Cargo

logs of the time record a variety of agricultural products shipped from

Fort Ross. Cattle, sheep, horses, hogs, hides, potatoes, apples, oats,

barley, eggs, butter, ducks, and pigeons were sold at markets in Sonoma

and Sacramento on behalf of Benitz. In the production, Benitz used the

indigenous Kashaya, who were obligated by the American government to

work on the ranch for $8 a month. In 1848 there were 162 Kashaya living

around Fort Ross.

With the beginning of the American Civil War,

Benitz increasingly got into economic difficulties. Until 1867 he sold

parts of his property, then he went to Argentina, where he ran cattle on

an estancia. His successors were Irish millwright and lumberjack James

Dixon and Virginia native Charles Snowden Fairfax. Dixon built a mill at

Fort Ross Creek and a large loading dock northwest of the small bay off

Fort Ross. Whether Fairfax ever came to Fort Ross is not known.

Dixon was primarily interested in the forestry use of the lands around

Fort Ross. Having no use for the kashaya, he sent her away. In the early

1870s they moved permanently to their previous winter quarters in

Huckleberry Hills and Abaloneville.

By 1873, Dixon had cleared

much of his property. He sold parts of the lands and settled further

north on the coast. His partner Charles Snowden Fairfax died

unexpectedly in 1869 at the age of 40. After 1873, more of the lands

belonging to Fort Ross were sold to dairy farmers.

George W.

Call, a native of Ohio, bought the largest part, around 7000 acres

including the fort. He followed the same management strategy as Wilhelm

Otto Benitz and focused on agriculture and animal husbandry. Together

with his Chilean wife Mercedes Leiva and their four children, Call

initially lived in the Rotschewhaus, named after Alexander Rotschew, the

last Russian commander of Fort Ross. In 1878, Call built a family home

on the north-west side of the bay and converted the Rotschevhaus into a

hotel. The orthodox chapel built by the Russians was used for weddings,

in winter also as a horse stable or for storing apples. Outside the

picket fence, the Calls built a post office and store. The post office

was operational until 1928, the shop only closing in the early 1960s.

One of George W. Call's most successful ventures was the production

of butter, which was in high demand in San Francisco. Between 1875 and

1899, an average of 20,000 pounds of butter were loaded and shipped

annually from Fort Ross Harbor. In addition, the calls expanded the

orchard planted by the Russians, which is still part of Fort Ross State

Park today.

In 1903, George W. Call sold approximately 21 acres of

his property, including Fort Ross and adjacent buildings, to the

California Historical Landmarks League. In 1906 it was transferred to

the state of California.

Less than a month later, the Fort Ross

buildings were badly damaged in the 1906 earthquake. It took ten years

before money was available for reconstruction.

In 1928, Fort Ross

was listed as one of five historic buildings on the California State

Historic Sites List. In 1936, a small group of Russian-Americans began

publishing newspaper articles on the history of Fort Ross under the name

of the Initiative Group for the Memorialization of Fort Ross. For the

community of Russian-Americans in California, which had grown rapidly

after the February Revolution of 1917, Fort Ross was a special

attraction: it stood for the lost homeland and thus became a focus of

their cultivation of Russian culture. To this day they celebrate

American Independence Day in Fort Ross.

In 1961, Fort Ross was

designated a National Historic Landmark, the highest federal level of

preservation. The following year, Fort Ross State Park was incorporated

as a California state park. On October 15, 1966, Fort Ross was listed on

the National Register of Historic Places. In 1970, the Kuskowhaus was

declared a National Historic Landmark as the only original part of the

building. In 1972, California State Route 1 (also: Highway One), which

until then ran straight through Fort Ross, was relocated to the east.

A Citizens Advisory Committee was established in April 1972, headed

by State Park Director William Penn Mott, Jr. This committee was made up

of local citizens, Russian-Americans and Kashaya Pomo and oversaw the

reconstruction of the fort on a voluntary basis until 1990.

In

July 1985, the new Fort Ross Visitor Center was dedicated. The cost of

$800,000 was funded in part by private donors. With the onset of

glasnost, more and more Russian visitors came to Fort Ross State

Historic Park. At the same time, a period of increased cultural exchange

and scientific engagement with Fort Ross began.

The Palisade

The palisade around Fort Ross has not

been preserved in its original condition. As early as 1833, the Mexican

military commander of Northern California, Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo,

wrote that the fort's walls could not withstand a cannon ball of any

caliber by this time large parts of the palisade had fallen into

disrepair. In 1929 the eastern, southern and parts of the western

palisade wall were renewed. After an archaeological dig in 1953, the

western and eastern palisade were completed. Finally, in 1974, the

picket was completely closed again.

The two Towers

Today there

are two wooden towers in the north-west corner of the palisade, facing

the sea, and opposite, in the south-east corner. They are replicas of

the original towers, badly damaged in the 1906 earthquake and later

demolished. The north-west (heptagonal) tower was rebuilt in 1950 and

1951 using Russian carpentry techniques. The condition of the

south-eastern (octagonal) tower dates from 1956/57. Originally, the

towers were equipped with cannons and served to defend the fort.

The old department store

The two-story warehouse (English Old Magasin

) served to store and sell goods. The modern reconstruction of the

building was completed in 2012, making it the youngest structure in the

fort ensemble. During archaeological investigations in 1981, the

excavators came across small glass beads that probably fell through

cracks in the wooden floor, from which archaeologists found the earlier

Location of the building closed. Now housed in the old warehouse, the

exhibit introduces visitors to the history of the fort's trade goods.

The Kuskow House

The so-called "Kuskovhaus" (English Kuskov

House) served as quarters for the first commander, Ivan Alexandrovich

Kuskov. It is one of the first buildings to fall into disrepair after

the Russian-American Company left. Today's Kuskowhaus was reconstructed

in the 20th century according to plans from 1817 and completed in 1983.

The lower floor consists of storage rooms and the upper floor consists

of living quarters. From the upper floor, the residents could watch all

the incoming ships. A room on the upper floor is now modeled after the

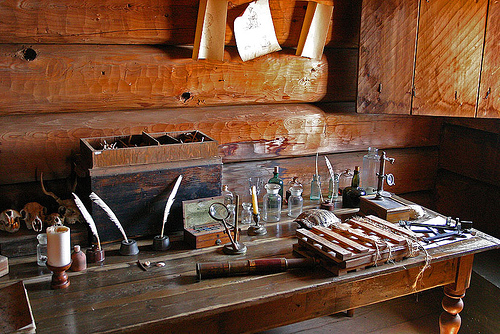

study where Russian naturalist Ilya Voznesensky spent his time at Fort

Ross in 1841.

The quarters of the company employees

The

quarters of the company's employees were housed in what is believed to

be one of the first buildings erected within the fort. The modern

reconstruction of the house was completed in 1981. It includes a storage

room, a wood workshop, a metal workshop, a prison room, several

dormitories and a dining room with attached oven for baking bread. The

current furnishing of the rooms does not necessarily reflect the

original use.

The Russian Chapel

The striking Russian wooden

chapel, very unusual for North America, is one of the most frequently

photographed buildings at Fort Ross today. The original building was

erected in 1825 with the own funds of the Russian residents of the fort

and the crew of the ship Kreiser. In the earthquake of 1906 the walls of

the chapel collapsed completely; the roof and the towers were preserved.

In the spring of 1916, the state of California donated $3,000 towards

reconstruction. Wood from a warehouse and from the company employees'

quarters was used for the reconstruction. During the reconstruction,

parts of the architecture were changed, and from 1955 the condition of

the building was finally adjusted to the original condition as part of a

renewed restoration measure.

On October 5, 1970, the chapel was

completely destroyed by fire. The chapel briefly lost its historic

landmark status in 1971-73, but donations from local residents,

Russian-Americans, and government agencies made it possible to rebuild.

The current building was erected in 1973 on the basis of

historical-archaeological studies and reflects - as far as possible -

the original condition of the chapel.

The Rotchev House

The

so-called "Rotschewhaus" (English Rotchev House) is the only building in

Fort Ross that has been largely preserved in its original condition. It

was renovated in 1836 for the last Russian commander of the fort,

Alexander Rotchev, based on an earlier building. In an inventory from

1841 it is referred to as the "new commander's house" - presumably to

distinguish it from the Kuskowhaus or "old commander's house".

In

Rotchev's time the house was comfortably furnished. In a report from

1841, the French Eugène Duflot de Mofras counts a selected library,

French wines, a piano and a Mozart score among the furnishings. All this

disappeared with the withdrawal of the Russians in 1841/42.