Location: Montezuma County, CO Map

Area: 52,485 acres (21,240 ha)

Mesa Verde National Park is located in Montezuma County, Colorado

state in United States. It is designated as an UNESCO World Heritage

Site for the ruined settlement of the Anasazi tribe. This historic

reserve covers a total area of 52,485 acres (21,240 ha).

Mesa Verde National Park protects a large area of various Anasazi

ruin that were build on various levels of the canyon at an elevation

between 1,900 and 2,600 meters above sea level. With over 700,000

visitors each year, it is one of the most visited parks in a state

of Colorado.

Mesa Verde settlement started as several small

shacks of ancient farmers who first settled here in the 6th century

AD. They supported their livelihood by growing maize on terraces on

top of a canyon. They constructed their shelters at the side of the

canyon to hide from sun rays. Around 13th century the settlement

grew in size as population exponentially increased. Several multi

story apartment buildings were erected to house the whole

population. It was constructed from yellow sandstone, mortar and

wooden beams that are supported the whole structure. Some walls have

collapsed, but stains on canyon ceiling give an idea where the

buildings once stood.

Anasazi Native tribes mysteriously

disappeared before the arrival of Europeans so we have no written

records of what happened to them. Pueblo natives that were related

to the Anasazi, claimed residents of Mesa Verde gathered for

celebration. The canyon was struck by an earthquake and all

unfortunate victims fell through the cracks. However these are just

oral tradition. Archeologists never discovered the real reason for

their disappearance.

The name of Mesa Verde is derived from a

eponymous plateau that rises 600 meters above the surrounding

terrain, those slopes are covered with pine forest. In Spanish "Mesa

Verde" can be translated as "green table" due to its appearance.

First European settlers came to the area in the 19th century. Mesa

Verde ruins were first explored by Richard Uezeril, an amateur

historian, and later by Swedish geologist Gustaf Nordenskiold. Mesa

Verde National Park was established in 1906 to protect ancient ruins

against possible vandalism. It was further added to the list of

UNESCO World Heritage site.

A 7-day entry pass to the Mesa Verde National Park costs $10 per

private vehicle fall-spring, and $15 per vehicle during the summer

months. Motorcyclists and individuals on non-commercial buses pay $5

per person fall-spring and $8 per person during the summer. An

annual pass, just for Mesa Verde, is available for $30.

There

are several passes for groups traveling together in a private

vehicle or individuals on foot or on bike. These passes provide free

entry at national parks and national wildlife refuges, and also

cover standard amenity fees at national forests and grasslands, and

at lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of

Reclamation. These passes are valid at all national parks including

Mesa Verde National Park:

The $80 Annual Pass (valid for

twelve months from date of issue) can be purchased by anyone.

Military personnel can obtain a free annual pass in person at a

federal recreation site by showing a Common Access Card (CAC) or

Military ID.

U.S. citizens or permanent residents age 62 or over

can obtain a Senior Pass (valid for the life of the holder) in

person at a federal recreation site for $80, or through the mail for

$90; applicants must provide documentation of citizenship and age.

This pass also provides a fifty percent discount on some park

amenities. Seniors can also obtain a $20 annual pass.

U.S.

citizens or permanent residents with permanent disabilities can

obtain an Access Pass (valid for the life of the holder) in person

at a federal recreation site at no charge, or through the mail for

$10; applicants must provide documentation of citizenship and

permanent disability. This pass also provides a fifty percent

discount on some park amenities.

Individuals who have volunteered

250 or more hours with federal agencies that participate in the

Interagency Pass Program can receive a free Volunteer Pass.

4th

graders can receive an Annual 4th Grade Pass that allows free entry

for the duration of the 4th grade school year (September-August) to

the bearer and any accompanying passengers in a private

non-commercial vehicle. Registration at the Every Kid in a Park

website is required.

In 2018 the National Park Service will offer

four days on which entry is free for all national parks: January 15

(Martin Luther King Jr. Day), April 21 (1st Day of NPS Week),

September 22 (National Public Lands Day), and November 11 (Veterans

Day weekend).

Ranger-led tours of the Cliff Palace, Balcony

House and Long House areas cost $5 per person per tour.

In

addition, the concession-management company Aramark, which also

operates the restaurants and inn in the Mesa Verde National Park,

offers considerably pricier -- in the $40 per person range -- guided

bus tours of the park that take visitors around to all the major

sites while offering history and commentary.

The first inhabitants of the Mesa Verde region, which stretches from southeast Utah to northwest New Mexico, were nomadic Paleo-Indians who arrived in the area from 9500 BC. They followed herds of big game and camped near rivers and streams, many of which dried up after the retreat of the glaciers that covered the San Juan Mountains. The earliest Paleo-Indians belonged to the Clovis culture and the Folsom tradition, which was largely determined by how they made spearheads and arrowheads. Although they left evidence of their presence throughout the region, there is little evidence that they lived in central Mesa Verde at that time. After 9600 BC. the nature of the area became warmer and drier, which led to the emergence of pine forests in central Mesa Verde and the animals living in them. Paleo-Indians began to populate Mesa Verde in increasing numbers from 7500 BC. BC, although it is not clear whether they were seasonal or permanent residents. The introduction of spear throwers during this period made it easier for them to hunt small game, which became important at a time when much of the big game had disappeared from the region.

In 6000 B.C. the Archaic period begins in North America.

Archaeologists disagree on the origin of the archaic population of Mesa

Verde. Some archaeologists believe they originated exclusively from

local Paleo-Indians, but others suggest that the variety of spear points

found in Mesa Verde indicates influence from surrounding areas,

including the Great Basin, the San Juan Basin, and the Rio Grande

Valley. Archaic people probably developed locally, but were also

influenced by contact, trade, and intermarriage with immigrants from

these outlying areas.

Early Archaic people living near Mesa Verde

used spear throwers and collected more variety of plants and animals

than the Paleo-Indians, while maintaining their predominantly nomadic

lifestyle. They inhabited the fringes of the Mesa Verde region, as well

as the mountains and canyons, where they created rock shelters and rock

carvings, and left evidence of animal hide and bone processing and flint

cutting. Environmental stability during this period stimulated

population growth and migration. Strong warming and droughts in the

periods from 5000 to 2500 years. BC e. may have prompted Middle Archaic

people to seek the cooler climate of Mesa Verde, whose higher elevation

brought increased snow cover which, combined with spring rains, provided

relatively abundant water.

By the end of the Archaic period, more

people lived in semi-permanent stone shelters that stored perishable

goods such as baskets, sandals, and mats. They began to make various

figures from branches, which usually resembled sheep or deer. The Late

Archaic is marked by an increase in trade in exotic materials such as

obsidian and turquoise. Sea shells from the Pacific coast came to Mesa

Verde from Arizona, and the archaic people used them in necklaces and

pendants. Rock art flourished, people lived in rudimentary houses made

of clay and wood. Their early attempts at plant domestication eventually

developed into sustainable agriculture that marked the end of the

Archaic period, around 1000 BC.

With the advent of maize in the Mesa Verde region around 1000 B.C and

the trend away from nomadism towards permanent settlements of pit

houses, the next period began, which archaeologists call the basket

maker culture or the Basketmaker era. The Basketmaker II people are

characterized by a combination of gathering and farming skills, using

spear throwers, and creating finely woven baskets in the absence of

pottery. By 300 B.C. corn became the staple food of the people in

Basketmaker II, who relied less and less on wild food sources and more

on domesticated crops. In addition to the fine basketry that gave the

era its name, the people of Basketmaker II made many household items

from plant and animal materials, including sandals, robes, bags, mats,

and blankets. They also made clay pipes and toys. The people of the

Basketmaker II era were relatively short and muscular, averaging less

than 1.7 m in height. Their skeletal remains show evidence of hard work

and extensive travel, including degenerative joint disease, healed

fractures, and mild anemia associated with iron deficiency. They buried

their dead close to their settlements and often placed luxury items in

the burials, which could indicate differences in relative social status.

The Basketmaker II people are also known for their distinctive rock art,

which can be found throughout Mesa Verde. They depicted animals and

people, both in abstract and realistic forms, in separate works and more

complex panels. A common subject was a hunchbacked flutist, whom the

Hopi people call Kokopelli.

By 500, spear throwers had been

replaced by bows and arrows and baskets by pottery, marking the end of

the Basketmaker II Era and the beginning of the Basketmaker III Era.

Ceramic vessels were a significant improvement over the resin-lined

baskets, gourds, and animal skin containers that were the region's main

water storage tanks. The pottery also protected the seeds from mold,

insects, and rodents. By 600, Mesa Verdeans were using clay pots to make

soups and stews. Around this time, year-round settlements appear. The

population of Mesa Verde around 675 was approximately 1,000 to 1,500

people. Beginning in 700, beans and new varieties of corn were

introduced to the region. By 775, some settlements had grown to

accommodate more than a hundred people. Around this time, construction

began on large above-ground storage buildings. The people of Basketmaker

III tried to store enough food for their family for one year, while

still being mobile so that they could quickly move their dwellings in

the event of resource depletion or constant crop shortages. By the end

of the 8th century, small settlements, which were usually used for ten

to forty years, were replaced by larger ones, which were continuously

inhabited for two whole generations. The people of Basketmaker III

established a tradition of holding large ceremonial gatherings near

public houses.

The year 750 marks the end of the Basketmaker III era and the

beginning of the Pueblo I period. There are major changes in the design

and construction of buildings and the organization of economic

activities. Food storage capacity increases from one year to two, and

construction of interconnected year-round houses, called pueblos,

begins. Many of the functions that were previously performed by pit

houses were transferred to these above-ground dwellings. This changed

the purpose of the pit houses from versatile spaces to those used

primarily for public ceremonies, although they still served as homes for

extended families, especially during the winter months. At the end of

the 8th century, the inhabitants of Mesa Verde began to build square

pits, which archaeologists call channels. They were usually 0.91 to 1.22

m deep and 3.7 to 6.1 m wide.

The first pueblos appeared in Mesa

Verde after about 650. By 850, more than half of Mesa Verdeans lived in

them. As the local population grew, the Puebloans could barely survive

on hunting, food gathering, and gardening, which made them increasingly

dependent on domestic corn. This transition from a semi-nomadic

lifestyle to a sedentary and communal lifestyle forever changed the

original Pueblo society. Within one generation, the average number of

households in these settlements increased from 1-3 to 15-20, with an

average population of about two hundred people. Population density

increased dramatically, and about a dozen families occupied about the

same place where two used to live. This increased protection against

raider raids and promoted closer cooperation between residents. It also

encouraged trade and intermarriage between clans, and by the end of the

8th century, as Mesa Verde's population increased with settlers from the

south, four different cultural groups lived in the same villages.

Large settlements of Pueblo I claimed resources ranging from 39 to

78 km². They were usually organized into groups of at least three

smaller settlements about 1 mile (1.6 km) apart. By 860, about 8,000

people lived in Mesa Verde. In the squares of large villages, the people

of Pueblo I dug large 74 m² pits that became central gathering places

for people. These structures are early architectural expressions of what

would eventually become the Pueblo II era "great houses" in Chaco

Canyon. Despite steady growth in the early to mid 9th century,

unpredictable rainfall and occasional droughts led to a dramatic

reversal in settlement patterns in the area. Many late Pueblo I villages

were abandoned in less than forty years of use, and by 880 Mesa Verde's

population was steadily declining. In the early 10th century, the region

experienced a massive population decline as people moved south of the

San Juan River into the Chaco Canyon in search of predictable rainfall

for agriculture. As the Mesa Verdeans moved south, where many of their

ancestors emigrated two hundred years ago, the influence of Chaco Canyon

grew, and by 950 Chaco Canyon displaced Mesa Verde as the cultural

center of the region.

The Pueblo II period is marked by the growth and spread of

communities centered around the "great houses" of Chaco Canyon. Despite

their involvement in the vast Chacoan system, Mesa Verdeans have

maintained a distinctive cultural identity, combining regional

innovation with ancient traditions, inspiring further architectural

advances. The pueblos of Mesa Verde of the 9th century influenced the

bicentennial construction of the "great houses" of the Chaco. A drought

in the late ninth century made farming in the Mesa Verdean drylands

unreliable, leading Mesa Verdeans to grow crops only near drains for the

next 150 years. By the beginning of the 11th century, productivity had

returned to normal levels. By 1050, the area's population began to

recover. As agricultural productivity increased, people returned to Mesa

Verde from the south. During the Pueblo II era, Mesa Verdean farmers

increasingly relied on stone tanks. In the 11th century, they built dams

and terraces near drainages and slopes to conserve soil and runoff.

These fields compensated for the danger of crop failure in the larger

drylands. By the middle of the 10th and beginning of the 11th centuries,

the ducts had evolved into smaller round structures called kivas, which

usually ranged from 3.7 to 4.6 m in diameter. These Mesa Verde style

kivas included an earlier feature called the sipapu, which is a hole dug

in the northern part of the chamber, symbolizing the exit point of the

Puebloan ancestors from the underworld. During this time, the Mesa

Verdeans began to move away from the post-and-mud jackal-style

structures that marked the Pueblo I period towards stone building, which

was in use in the region as early as 700 but was not widespread until

the 11th and 12th centuries.

The expansion of Chaco Canyon

influence into the Mesa Verde region left its most visible mark in the

form of Chaco-style "great houses" that became the center of many Mesa

Verde villages after 1075. The "Distant View House", the largest of

these, is considered a classic Chaco "mansion", the construction of

which probably began between 1075 and 1125, although some archaeologists

claim that it was started as early as 1020. The wooden and earthen

pueblos of that era were generally used for about twenty years. In the

early 12th century, the center of the region shifted from the Chaco to

Aztec, New Mexico, in southern Mesa Verde. By 1150, the drought again

hit the inhabitants of the region, causing the construction of the

"great house" in Mesa Verde to be temporarily stopped.

A severe drought from 1130 to 1180 led to a rapid population decline

in many parts of the San Juan Basin, especially in the Chaco Canyon. As

the vast Chaco system collapsed, more and more people moved into Mesa

Verde, resulting in a significant population growth in the area. Much

larger settlements emerged, numbering between six hundred and eight

hundred people, limiting the mobility of Mesa Verdeans, who in the past

often moved their homes and fields as part of their agricultural

strategy. In order to support this ever-increasing population, it was

necessary to devote more and more time to agriculture. Population growth

also led to increased tree cutting, which reduced the habitat for many

of the wild plant and animal species that Mesa Verdeans relied on,

further exacerbating their dependence on domesticated crops that were

declining due to drought. The Chaco system brought large quantities of

imported goods to Mesa Verde in the late 11th and early 12th centuries,

including pottery, shells, and turquoise, but by the end of the 12th

century, when the system collapsed, the amount of goods dropped sharply

and Mesa Verde found itself isolated. from surrounding regions.

For about six hundred years, most Mesa Verdean farmers lived in small

one- or two-family homesteads on the plateau. Usually these estates were

located near fields and within walking distance of water sources. This

practice continued until the mid to late 12th century, but by the early

13th century they began to move into canyons that were close to water

sources and within walking distance of their fields. In the middle of

the Pueblo III era, Mesa Verdean villages prospered. Architects built

massive multi-storey buildings, while artisans decorated pottery with

increasingly complex designs. Structures built during this period have

been described as some of the world's greatest archaeological treasures.

Pueblo III stone buildings were typically used for approximately fifty

years, more than double the useful life of Pueblo II jackal structures.

In others they lived continuously for two hundred years or more.

Architectural innovations such as towers and multi-wall structures also

make their first appearance in the Pueblo III era. The population of

Mesa Verde remained fairly stable during the drought of the 12th

century. At the beginning of the 13th century, about 22,000 people lived

here. During the following decades, the area saw a moderate increase in

population, and then a sharp increase from 1225 to 1260. Most of the

inhabitants of the region lived on the plains to the west of the

mountain. Others populated the edges and sides of the canyons in

multi-family settlements that grew to unprecedented proportions as the

population grew. By 1260, most Mesa Verdeans lived in large pueblos,

which housed several families and over a hundred people. In the 13th

century, the Mesa Verde region experienced 69 years of below-average

rainfall, and after 1270, the area suffered particularly low

temperatures. Dendrochronology shows that the last tree cut down for

building on the hill was cut down in 1281. During this time, pottery

imports to the region declined greatly, but local production remained

stable. Despite difficult conditions, the Puebloans continued to

cultivate the area until a very dry period from 1276 to 1299 ended a

seven hundred year period of continuous human settlement of Mesa Verde.

Archaeologists call this period the "Great Drought". The last

inhabitants of Mesa Verde left the territory in 1285.

During the Pueblo III period (1150–1300), the Mesa Verdeans built numerous masonry towers that probably served as defensive structures. Hidden tunnels were also used, connecting the towers with the respective kivas. The war was fought using the same weapons that Mesa Verdeans used to hunt, including bows and arrows, stone axes, and wooden clubs and spears. They also made shields from skins and baskets, which were used only during battles. Periodic wars took place on the plateau throughout the thirteenth century. Civic leaders in the region likely gained power by distributing food during a drought. This system likely broke down during the "Great Drought", leading to intense warfare between rival clans. Increasing economic and social uncertainty in the last decades of the century has led to large-scale conflicts. Evidence of partially burned villages has been found. The inhabitants of one village appear to have been the victims of a massacre. Evidence of violence and cannibalism has been found and documented in the central Mesa Verde region. Although much of the violence that peaked between 1275 and 1285 is usually attributed to clashes between Mesa Verdeans, archaeological evidence found proves that violent interactions also took place between Mesa Verdeans and people from outside the region. Many of the victims showed signs of skull fractures, and the uniformity of the damage suggests that most were inflicted with a small stone axe. Other victims were scalped, dismembered and eaten. Anthropophagy (cannibalism) may have been used as a survival strategy during times of famine. Archaeological evidence shows that violent conflict was widespread in North America in the late 13th and early 14th centuries and was likely exacerbated by global climate change, which negatively affected food supplies throughout the continent.

In the early 13th century, the Mesa Verde region experienced unusually cold and dry conditions. This may have led to migration to Mesa Verde from less hospitable places. The added population has increased pressure on the region's environment, further straining the drought-stricken agricultural community. The region's bimodal rainfall pattern, which brought rain in spring and summer and snowfall in autumn and winter, began to break after 1250. After 1260, Mesa Verde experienced a rapid population decline as tens of thousands of people emigrated or starved to death. Many small communities in the Four Corners area were also abandoned during this period. Ancestral Puebloans had a long history of migration in the face of environmental instability, but the decline of Mesa Verde's population in the late 13th century was notable for the fact that the region was almost completely deserted and no descendants returned to rebuild settlements. Although drought, resource depletion, and overpopulation all contributed to instability during the last two centuries of the Ancestral Pueblos, their over-reliance on the corn crop is considered a fatal flaw in their survival strategy. The people who left Mesa Verde left little direct evidence of their emigration, but left behind household items, including kitchen utensils, tools, and clothing, which has given archaeologists the impression that the emigration was accidental or hasty. An estimated 20,000 people lived in the region in the 13th century, but the area was almost uninhabited by the early 14th century. Many emigrants moved to southern Arizona and New Mexico. Although the rate of settlement is unclear, the growth in the outback areas directly corresponds to the period of emigration from Mesa Verde. Archaeologists believe that the Mesa Verdeans who settled in the areas near the Rio Grande, where Mesa Verdean pottery became widespread in the 14th century, were related to the families they joined, rather than being unwanted aliens. Archaeologists view this migration as a continuation, rather than a disintegration, of the society and culture of the Ancestral Pueblos. Many Mesa Verdeans moved to the banks of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona. While archaeologists tend to focus on the push factors that pushed Mesa Verdeans away from the region, there were also several environmental pull factors such as warmer temperatures, better farming conditions, abundance of timber, and bison herds that stimulated resettlement in the area near the Rio Grande. In addition to numerous settlements along the Rio Grande, modern descendants of Mesa Verdeans live in pueblos in Acoma, Zuni, Jemes, and Laguna.

Although the Chaco Canyon may have exercised regional control over

Mesa Verde in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, most

archaeologists view the Mesa Verde region as a collection of small

communities that were never fully integrated into a larger civil

structure. Several ancient bermed roads have been found in the area,

ranging in width from 4.6 to 13.7 m. Most of the roads probably

connected communities and shrines, others surrounded large residential

buildings. The extent of the road network is unclear, but no road has

been found to directly connect Mesa Verde and the Chaco Canyon

settlements.

Ancestral Pueblo shrines, called Herraduras, have

been found along stretches of roads in this region. Their purpose is

unclear, but several C-shaped herraduras have been excavated and they

are believed to have been "pointed sanctuaries" used to mark the

location of large houses.

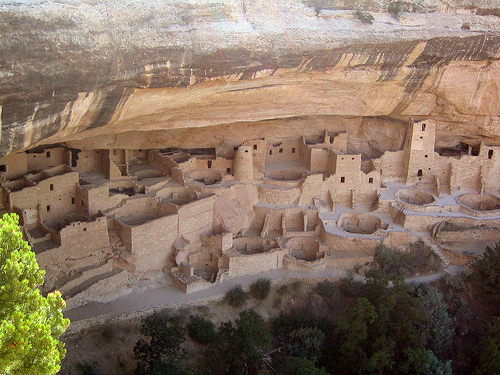

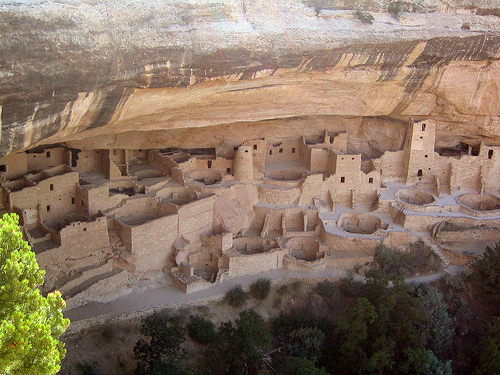

Mesa Verde is well known for the large number of well-preserved cliff dwellings, houses built in niches, or rock ledges along the canyon walls. The houses in these niches were mostly built from blocks of hard sandstone, fastened together and plastered with mud mortar. The specific structures had much in common but were generally unique in form due to the individual topography of the various alcoves along the canyon walls. Unlike earlier structures and mesa-top villages, Mesa Verde's rock dwellings reflected a region-wide trend towards consolidating the region's growing population into tight, well-defended neighborhoods during the thirteenth century.

The inhabitants of Mesa Verde used astronomical observations to plan agricultural work and religious ceremonies, using both natural landscape features and stone structures built for these purposes. Some of the "great houses" in this region had windows, doors and walls oriented to the cardinal points, and were located along the path of the sun, whose rays indicated the change of seasons. The Temple of the Sun at Mesa Verde is believed to have been an astronomical observatory. The temple was D-shaped and its orientation was 10.7 degrees away from true east and west, indicating that the temple builders understood the cycles of the sun and moon, since this orientation corresponds to the largest range between the northern and southern declination limits. the moon, which is observed every 18.6 years, and the sunset during the winter solstice, which could be observed from the platform in the southern part of the Cliff Rock Palace. At the bottom of the canyon was the Temple of the Sun firepit, which was illuminated by the first rays of the rising sun during the winter solstice. The Temple of the Sun is one of the largest, purely ceremonial structures ever built by the Pueblo ancestors.

Beginning in the 6th century, farmers in central Mesa Verde grew corn, beans, and cucurbits. The combination of corn and beans provided Mesa Verdeans with the amino acids of a complete protein. When conditions were good, 3 or 4 acres (1.2 or 1.6 ha) of land could provide enough food for a family of three or four for a year, provided the agricultural products were supplemented with game and wild plants. As Mesa Verdeans increasingly relied on corn as their staple food, the success or failure of crops affected their lives in many ways. Before the advent of pottery, food was baked, fried, and dried. Hot stones thrown into the containers could bring water to a brief boil, but since legumes need to be boiled for an hour or more, they were not widely used. With the spread of pottery throughout the region, the increase in the proportion of legumes in the diet provided a high-quality protein supply that reduced the population's dependence on hunting. It has also contributed to higher corn yields as the legumes add much-needed nutrients to the soil in which they are grown. Most Mesa Verdeans practiced dry farming, relying only on rain to water their crops, but others used runoff, springs, diversions, and natural pools to farm. Starting from the 9th century, they dug and maintained reservoirs into which they collected runoff from summer rains and spring snowmelt. Some crops were watered by hand. Archaeologists believe that until the 13th century, springs and other sources of water were considered public resources, but as Mesa Verdeans amalgamated into ever larger cities built around water sources, control of the water supply was privatized and consumption was limited to members of a particular community. . Between 750 and 800, the Mesa Verdeans began building two large structures at the bottom of the canyon, the Morefield and Box Elder reservoirs. Shortly thereafter, work began on two more tanks, Far View and Sagebrush, which were about 27m across and built on top of a plateau. In 2004, the American Society of Civil Engineering designated these four buildings National Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks.

The Mesa Verdeans usually hunted small local game, but sometimes organized hunting parties that traveled long distances. The main sources of animal protein for them were deer and rabbits, but sometimes they hunted bighorn sheep, antelopes and elks. Domestication of turkeys began around the year 1000, and by the 13th century, consumption of these birds peaked, displacing deer as the main source of protein in many places. These domesticated turkeys consumed large amounts of corn, further increasing the population's dependence on the crop. Puebloans wove blankets from turkey feathers and rabbit fur, and made items such as awls and needles from turkey and deer bones. Despite the presence of fish in the rivers and streams of the area, archaeological evidence suggests that it was rarely consumed. Mesa Verdeans supplemented their diet by collecting seeds and fruits from wild plants. Depending on the season, nuts, juniper berries, physalis, sunflower seeds, yucca, as well as various types of herbs and cacti were collected. Prickly pear fruits were a source of natural sugar. They also smoked wild tobacco. Since the ancestors of the Pueblos considered sacred all the material consumed and discarded by their communities, they treated with reverence the garbage and waste dumps. Since the Basketmaker III period, Mesa Verdeans often buried their dead in these garbage mounds.

Scholars are divided over whether pottery was invented in the Four Corners region or was introduced from the south. Samples of shallow unfired earthenware bowls found at Cañon des Cheys indicate that the first pottery may have been made by using such earthenware bowls to roast or dry seeds. Repeated use made these bowls hard and waterproof, which may have been the first fired pottery in the region. An alternative theory suggests that pottery originated in the Mogollon Rim area in the south, where clay bowls were used for the first few centuries AD. Other scholars believe that pottery was brought to Mesa Verde from Mexico from around 300 AD. There is no evidence of ancient pottery markets in the region, but archaeologists believe that local potters traded decorative items between families. Pots made from crushed volcanic rocks from places like Mount Ute[en] were more resistant to water and fire and were in demand, so Mesa Verdeans from all over the region traded them. Neutron activation analysis indicates that much of the black-on-white pottery found in Mesa Verde was locally produced. Chalk clays from the Dakota and Menefi Formations were used to make black-on-white pieces, and clays from the Mancos Formation were used for corrugated vessels. Evidence that pottery of both types moved between several locations in the region suggests interactions between groups of ancient potters, or they may have had a common source of raw materials. Archaeological evidence shows that almost every household had at least one family member who was engaged in pottery. For firing finished products, trench kilns were used, which were built far from the pueblo and closer to the sources of firewood. Their sizes vary, but the largest were up to 7.3 m long and are thought to have been communal ovens used by several families. Drawings were applied to ready-made ceramic vessels with a brush made of yucca leaves with paints made from iron, manganese, cleome and descuria. Much of the pottery found in 9th-century villages was for individuals or small families, but as communal life expanded in the 13th century, many larger vessels were made for communal feasting. Corrugated decorations appear on Mesa Verdean pottery after 700, and by 1000 entire vessels were made embossed. This technique created a rough outer surface that was easier to hold than the usual smooth surface. By the 11th century, these corrugated vessels, which dissipated heat more efficiently than smooth ones, had largely replaced the old style. Corrugation probably originated when ancient potters tried to imitate the visual properties of basketry. Corrugated wares were made from clay sourced not only from the Menefi Formation but also from other formations, suggesting that ancient potters chose different clays for different styles. The potters also chose clays and changed the firing conditions to achieve certain colors. Under normal conditions, the clay pots from the Mancos Formation turned gray when fired, and the clay pots from the Morrison Formation turned white. Clay from southeastern Utah turned red when fired in a high oxygen environment.

Rock paintings can be found throughout the Mesa Verde region, but are

scattered unevenly and intermittently. In some places there are a lot of

them, in others they are not at all, and there are a lot of images

relating to some periods of time, but few to others. Styles also change

over time. Imagery is relatively rare on the Mesa Verde Plateau itself,

but abundant in the middle region of the San Juan River, which may

indicate the river's importance as a travel route and a key source of

water. Common motifs in the region's rock art include anthropomorphic

figures in processions and during copulation or childbirth, handprints,

wavy lines, spirals, concentric circles, images of animals and hunting

scenes. As the region's population declined sharply in the late 13th

century, Mesa Verdean rock art increasingly shifted to depictions of

shields, warriors, and battle scenes. Modern Hopi interpret the

petroglyphs at Mesa Verde's Cape Petroglyphs as depictions of various

clans of people.

Beginning in the late Pueblo II period (1020)

and continuing until Pueblo III (1300), Pueblo ancestors from the Mesa

Verde region created plaster frescoes in their "great houses",

especially the kivas. The murals contained both painted and inscribed

images of animals, humans, and designs used in textiles and ceramics

since the Basketmaker III era. Other frescoes depicted triangles and

hills, thought to represent mountains and hills in the surrounding

landscape. Frescoes were usually located on the front side of the kiva

bench and surrounded the room. Common motifs are geometric patterns,

reminiscent of the symbols used in ceramics, and zigzags, representing

the stitches used in basket making. The frescoes were painted in red,

green, yellow, white, brown and blue. These drawings were still used by

the Hopi in the 15th and 16th centuries.

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mesa Verde

National Park has a humid continental climate (Dfb). According to the

USDA, the plant hardiness zone at Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters

at 2,119 m above sea level is 6b with an average annual extreme minimum

temperature of −17.8°C.

The precipitation pattern in the region

is bimodal, meaning that agriculture is supported by snowfall in winter

and autumn and rainfall in spring and summer.[38] Water for agriculture

and consumption was provided by summer rains, winter snowfalls, and

springs in and around Mesa Verde settlements. At an altitude of 2100 m,

the middle part of the mountain was usually 5.5 ° C colder than its top,

which reduced the amount of water needed for agriculture. The dwellings

in the rocks were built taking into account the use of solar heat. The

winter angle of the sun warmed the brickwork of the rock dwellings, a

warm breeze blew from the valley, and the air in the niches of the

canyon was ten to twenty degrees warmer than at the top of the hill. In

summer, when the sun was high overhead, most of the village was

protected from direct sunlight in rock dwellings.

Mexican-Spanish missionaries and explorers Francisco Atanasio

Dominguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, who were looking for a route

from Santa Fe to California in 1776, documented their journey. They

reached the plateau, which was given the name Mesa Verde because of the

abundance of trees that covered it, but they did not get close enough to

discover the ancient stone villages.

The Mesa Verde region had

long been occupied by the Ute, and an 1868 agreement between them and

the U.S. government recognized Ute ownership of all Colorado land west

of the continental divide. After interest in land in western Colorado

arose, a new treaty of 1873 left the Jutes with a strip of land in

southwestern Colorado between the New Mexico border and 15 miles to the

north. Most of Mesa Verde lies within this strip of land. The Jutes

wintered in warm, deep canyons and took refuge there and on the Mesa

Verde Plateau. Considering the dwellings on the rocks to be the sacred

places of their ancestors, they did not live in ancient dwellings.

From time to time, trappers and prospectors visited the region, and

one of them, John Moss, shared his observations in 1873. The following

year, Moss led noted explorer and photographer William G. Jackson

through the Mancos Canyon at the foot of Mesa Verde. There, Jackson

photographed and published a typical rock dwelling on a cliff.

Archaeologist William H. Holmes retraced Jackson's route in 1875. The

Jackson and Holmes reports were included in the 1876 report of Ferdinand

Hayden's explorations, one of four federally funded studies of the

American West. These and other publications have led to proposals for a

systematic study of the archaeological sites of the Southwest.

With the intention of finding ancestral Pueblo settlements, Virginia

McClurg, a journalist for The New York Daily Graphic, visited Mesa Verde

in 1882 and 1885. Her group rediscovered the Rock Echo House, the

Three-Level House, and the Balcony House in 1885. These discoveries

inspired her to work to protect these dwellings and artifacts.

The Weatherill ranching family befriended the Utes near their ranch southwest of Mancos. With the approval of the Ute tribe, the Weatherills were allowed to bring cattle to the lower, warmer plateaus of the current Ute reservation in winter. Rumors were already circulating about the "Great Houses" of the Pueblo ancestors, and Akowitz, a Ute Indian, told the Weatherills about the rock dwellings in Mesa Verde: "Deep in this canyon and at its top are many houses of ancient people. One of these houses, high in the rock, is larger than all the others. The Ute never go there, it's a sacred place." On December 18, 1888, Richard Weatherill and cowboy Charlie Mason rediscovered Cliff Palace after seeing its ruins from the top of Mesa Verde. Weatherill gave the ruins its modern name. Richard Weatherill and his family and friends subsequently explored the ruins and collected many artifacts, some of which they sold to the Colorado Historical Society and most of which they kept. Among the people who explored the cliff dwellings with the Weatherills was the mountaineer, photographer, and writer Frederick H. Chapin, who then visited the region in 1889 and 1890. He described the landscape and the ruins in an 1890 article and later in The Land of the Rock Dwellers (1892), which he illustrated with hand-drawn maps and personal photographs.

In 1891 the Weatherills were visited by Gustav Nordenskiöld, son of the polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Nordenskiöld Jr. was an accomplished mineralogist who introduced scientific methods into the collection of artifacts, documented locations, photographed in detail, plotted diagrams, and compared what he observed with existing archaeological literature as well as with the experience of the Weatherills. He discovered many artifacts and sent them to Sweden, where they ended up in the National Museum of Finland. Nordenskiöld published The Rock Dwellers in Mesa Verde in 1893. When Nordenskiöld sent his collection of artifacts to Sweden, it raised concerns about the need to protect the lands of Mesa Verde and its historical riches.

In 1889, Goodman Point Pueblo of Hovenweep National Monument became

the first pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Mesa Verde region to

receive federal protection from the US government. Virginia McClurg

worked hard between 1887 and 1906 to educate the United States of

America and the European community about the importance of protecting

historic materials and dwellings in Mesa Verde. Her intentions included

enlisting the support of 250,000 women through the Federation of Women's

Clubs, writing and publishing poetry in popular magazines, giving

speeches domestically and internationally, and forming the Colorado Rock

Dwellers Association. The goals of this association were to protect the

resources of the Colorado cliff dwellings, to recover as many of the

original artifacts as possible, and to share information about the

people who lived there. Associates in the defense of Mesa Verde and

prehistoric archaeological sites included Lucy Peabody, who met with

members of Congress in Washington to rally their support. Former Mesa

Verde National Park Manager Robert Hader expressed his belief that the

park could have been much more important given the hundreds of artifacts

captured by Nordenskjöld.

By the end of the 19th century, it

became clear that Mesa Verde needed protection from people who came to

Mesa Verde and collected or sold their own collection of artifacts. In a

report to the US Secretary of the Interior, Smithsonian Institution

ethnologist Jesse Walter Fukes described the vandalism at Cliff Palace

in Mesa Verde:

Lots of "curiosity seekers" remained in the ruins for

several winters, and many hundreds of copies were reportedly carried off

the mountain and sold to private individuals. Some of these objects are

now in museums, but many are forever lost to science. In order to get

hold of this valuable archaeological material, walls were broken down

... often just to let light into dark rooms. The floors were invariably

opened up, and buried kivas mutilated. To facilitate this work and get

rid of dust, large holes were made in the five walls that form the

facade of the ruins. The beams were used as firewood to such an extent

that now there is not a single roof left. This destructive work, added

to the destruction from rain erosion, left Cliff Palace in a sorry

state.

Many artifacts from Mesa Verde are now in museums and

private collections in the United States and around the world. For

example, a representative set of ceramic vessels and other objects is

now in the British Museum in London. In 1906, President Theodore

Roosevelt approved the creation of Mesa Verde National Park and the

Federal Antiquities Act of 1906. The park was an attempt to "preserve

the creations of man" and was the first park created to protect a site

of cultural significance. The park was named by the Spanish term "green

table" because of the forests of juniper and piñon.

Excavations

and protection

Between 1908 and 1922 the ruins of the Spruce Tree

House, the Cliff Palace and the Temple of the Sun were restored. Most of

the early work was led by Jesse Walter Fuchs. In the 1930s and 1940s,

workers in the Civilian Conservation Corps played a key role in

excavating, constructing trails and roads, creating museum exhibits, and

constructing buildings in Mesa Verde. From 1958 to 1965 the Mount

Weatherill Archaeological Project carried out archaeological

excavations, site stabilization and surveys. Thanks to the excavation

and study of eleven sites by the Mount Weatherill Project, it is

considered the largest archaeological project in the United States. As

part of the project, excavations of the Long House and the Mug House

were carried out. In 1966, like all historic districts administered by

the US National Park Service, Mesa Verde was listed on the US National

Register of Historic Places, and in 1987, the entire Mesa Verde

administrative region was listed on the register. In 1978 it was

included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. In 2015, Sunset magazine

named Mesa Verde National Park the "Best Cultural Attraction" in the

Western United States.

Clashes between non-indigenous environmentalists and local tribes

surrounding the ruins in Mesa Verde began even before the park was

officially founded. Conflicts over who claimed the land surrounding the

ruins erupted in 1911 when the US government wanted to allocate more Ute

land for the park. The Jutes were reluctant to agree to the land

exchange offered by the government, noting that the land the tribe owned

was the best land. Frederick Abbott, working with Bureau of Indian

Affairs official James McLaughlin, declared himself an ally of the Ute

Indians in the negotiations. Abbott later claimed that "the government

was stronger than a cliff", saying that "when the government finds old

ruins on land that it wants to use for public purposes, it has the right

to take them away..." Feeling that they had no other options, the Utes

reluctantly agreed to trade 10,000 acres on Mesa Verde for 19,500 acres

on Mount Utah.

The Ute continued to fight the Bureau of Indian

Affairs to keep Ute land from being included in the park. In 1935, the

Bureau of Indian Affairs attempted to reclaim some of the land it had

sold in 1911. In addition, Mesa Verde National Park Administrator Jesse

L. Nusbaum later admitted that the land on Mount Utah, which was bought

for Mount Chapin in 1911, belonged to the tribe anyway, which meant that

the government traded the land, which never belonged to him.

Other issues not related to land disputes have arisen as a result of the

park's activities. In the 1920s, the park began offering "Indian

Ceremonies" performances, which became popular with visiting tourists.

However, the ceremonies did not really reflect either the rites of the

ancient Puebloans, who lived in rock dwellings, or the rites of the

modern Jutes. Navajo day laborers performed these rituals, resulting in

"the wrong Indians doing the wrong dance in ... the wrong land." In

addition to the inaccuracies of the ceremonies, the question of whether

the Navajo dancers were fairly paid also led to questions regarding the

lack of local American Indians employed in other positions in the park.

The entrance to Mesa Verde National Park is located on US Highway

160, about 14 km east of the village of Cortez and 11 km west of Mancos,

Colorado. The park covers 52,485 acres (21,240 ha). It contains 4372

documented sites, including over 600 cliff dwellings. It is the largest

archaeological reserve in the United States. It protects some of the

most important and best preserved archaeological sites in the country.

The park initiated the Archaeological Preservation Program in 1995. It

analyzes data on how monuments are constructed and used.

The Mesa

Verde Visitor and Research Center is located off Highway 160, in front

of the park entrance. The visitor and research center opened in December

2012. Mount Chapina (the most popular area) is 32 km from the visitor

center. Mesa Verde National Park is under exclusive federal

jurisdiction. Because of this, all law enforcement, emergency medical

services, and firefighting are handled by federal rangers from the

National Park Service. Access to park facilities depends on the season.

Three of the rock dwellings on Mount Chapina are open to the public. The

Chapin Archaeological Museum is open all year round. The Spruce Tree

House is also open all year round, weather permitting. Access to Balcony

House, Long House and Cliff Palace requires the purchase of tour tickets

for tours with a ranger. Many other residences are visible from the road

but are closed to tourists. The park has hiking trails, a campground,

and, during the peak season, services for food, fuel, and lodging. In

winter they are not available.

The first constructed

administrative buildings of the park, located on Mount Chapina, form an

architecturally significant complex. Built in the 1920s, the Mesa Verde

Administration Complex was one example of a park service that used

cultural design to create park facilities. The area was designated a

National Historic Landmark in 1987.

Between 1996 and 2003, the park suffered from several wildfires. The

fires, many started by lightning during a drought, burned 28,340 acres

(11,470 ha) of forest, more than half of the park. During these fires,

two objects of rock art were destroyed, the museum was almost destroyed

- the first of those built in the system of national parks and the House

on a Spruce Tree, the third largest rock house in the park.

Before the fires of 1996-2003, archaeologists had managed to examine

about ninety percent of the park. Dense undergrowth and tree cover kept

many ancient sites hidden from view, but 593 previously undiscovered

sites were discovered after the fires - most of them from the

Basketmaker III and Pueblo I periods. Many water-saving features were

also discovered during the fires, including 1189 dams, 344 terraces and

5 reservoirs dating back to the Pueblo II and III periods. In February

2008, the Colorado Historical Society decided to invest part of its $7

million budget in a project to grow culturally modified trees in the

national park.

Mount Ute Tribal Park

Mount Ute Tribal Park

adjoins Mesa Verde National Park to the east. It covers an area of about

125,000 acres (51,000 ha) along the Mancos River. The park contains

hundreds of archaeological sites, rock dwellings, petroglyphs, and wall

paintings from ancestral Puebloan and Jute cultures. Ute guides provide

background information about the people, culture, and history of the

parklands. It was selected by National Geographic Traveler magazine as

one of the "80 World Travel Destinations for the 21st Century" and one

of nine selected locations in the United States.

In addition to rock dwellings, Mesa Verde is home to many mountaintop

ruins. Sites open to the public include Far View Complex, Cedar Tree

Tower on Mount Chapin, and Badger House Community on Mount Weatherill.

"Balcony House"

"Balcony House" is located on a high ledge, with

a facade directed to the east. In its 45 rooms and 2 kivas it would be

cold in winter. Visitors on ranger-led tours enter by climbing a 32-foot

ladder and crawling through a small 12-foot tunnel. The exit (a series

of hooks in the crevice of the cliff) was considered the only entrance

and exit for the inhabitants of the house, which made the small

settlement safe and easy to defend. One log from the house is dated

1278, so this house was probably built shortly before the people of Mesa

Verde left the area. The house was officially excavated in 1910 by Jesse

L. Nusbaum, who was the first archaeologist of the National Park Service

and one of the first managers of Mesa Verde National Park.

Cliff

Palace

The most famous rock dwelling in Mesa Verde, these multi-story

ruins are located in the largest alcove in the center of Mesa Verde

Mountain. Its façade faces south and southwest, which gives more heat

from the sun in winter. The building was built over 700 years ago from

sandstone, wooden beams and mortar. Many rooms were brightly colored.

Cliff Palace had a population of approximately 125, but was probably an

important part of a larger community of sixty neighboring pueblos that

had a population of six hundred or more. With 23 kivas and 150 rooms,

Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park.

"Long House"

Located on Mount Weatherill, Longhouse is the second

largest village in Mesa Verde. About 150 people lived here. The site was

excavated from 1959 to 1961 as part of the Mount Weatherhill

archaeological project. The Longhouse was built around 1200 and was in

use until 1280. The cliff dwelling includes 150 rooms, a kiva, a tower,

and a central square. Its rooms are not clustered like typical cliff

dwellings. Stones were used without shaping for fit and stability. On

the two upper ledges there is a place for storing grain. The water

source is several hundred feet away and the exits are at the back of the

village.