Location: Masvingo Map

Area: 722 hectares (1,780 acres)

Great Zimbabwe (also Old Zimbabwe, English Great Zimbabwe) is a

ruined city located 39 kilometers from Masvingo in Masvingo Province

in Zimbabwe. The name Zimbabwe means Great Stone Houses or Honored

Houses depending on the dialect. The settlement on the plateau of

the same name was the capital of the Munhumutapa Empire (also

Monomotapa Empire), which also included parts of Mozambique in

addition to today's Zimbabwe. In its heyday from the 11th to the

mid-15th century, Greater Zimbabwe had up to 18,000 inhabitants, was

used by the monarchs of Zimbabwe as a royal palace and was the

center of political power. The wealth of the metropolis was based on

cattle breeding, gold mining and long-distance trade. Evidence of

the spiritual center are the Zimbabwe birds made of soapstone. The

complex is the largest pre-colonial stone structure in sub-Saharan

Africa and one of the oldest.

The city was already deserted

and falling into disrepair when Europeans first saw it in the 16th

century. For a long time it was erroneously interpreted as the home

of the Queen of Sheba. However, the results of archaeological

research refute this thesis; the date of origin of the complex is

assumed to be the late Iron Age, which corresponds to the 11th

century in this region.

The ruins of Greater Zimbabwe have

featured on Zimbabwe's national coat of arms since 1981 and have

been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1986.

Location

Greater Zimbabwe is located 240 kilometers south of the

capital Harare and about 25 kilometers south-southeast of Masvingo,

formerly Fort Victoria, in Masvingo Province in the southern half of

Zimbabwe. The ruins are at an altitude of 1140 m. Immediately to the

north, about two kilometers away, begins the landscape park Mutirikwi

Recreational Park with Lake Kyle and Lake Mutirikwi. This reservoir

covers about 90 km² and has been dammed since 1960 when the Kyle Dam was

built on the Mutirikwi River, a tributary of the Runde.

The

location on this plateau offered the city natural protection against

sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis). Spread by the tsetse fly,

this disease can kill humans and cattle, but tsetse flies are only found

in low-lying areas.

Southwest of the ruins is the Morgenster

Mission, a mission station and hospital built by John T. Helm in 1894 on

behalf of the Dutch Reformed Church.[3] To the north is the road to

Masvingo, and to the east is the small town of Dorogoru.

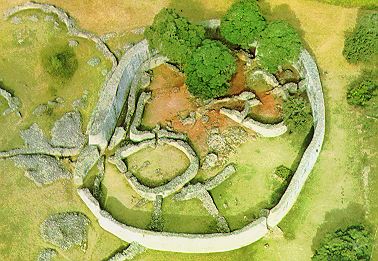

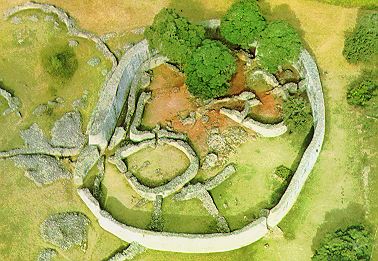

outline

The site covers a fenced area of 722 hectares and is divided into four

parts: on the hill is the so-called mountain ruin, in the valley floor

to the south are the enclosures, to the east is the Shona village museum

and to the west of the enclosures is the modern infrastructure with a

hotel, Campsite, administrative buildings and access roads.

To

the south of the mountain ruins, a relatively wide valley opens up, in

which stand the enclosures, of which the Great Enclosure is the

southernmost structure. To the west, from north to south, are Outspan

Ruins, Camp Ruins, and Hilltop Ruins. The remaining, smaller ruins are

primarily named after their respective explorers: just north of the

Great Wall are Ruins #1, Posselt Ruins, Renders Ruins, and Mauch Ruins.

East of this are the ruins of Philips, the Maund and the East.

Geology

The area on which the ruins of Great Zimbabwe are located is

about 110 kilometers east of the Great Dyke, where coveted precious

metals, especially gold, were mined. The subsoil of Greater Zimbabwe

itself is predominantly granite with massive veins of gneiss formed by

contact metamorphism in the early Precambrian. Geological investigations

revealed that the granite blocks used to build the walls were mainly

biotite-based. The composition is 35% quartz, 58% feldspar (microcline

28%, plagioclase 30%), 4% biotite, 3% muscovite and less than 1% iron

ore. Diorite was used as a harder stone to work the granite for the

buildings.

Climate

The place is located in a subtropical to

tropical climate zone with humid, sometimes hot and humid summers and a

dry winter season. The average annual temperature in Greater Zimbabwe is

between 20.8 and 26.1 °C. The warmest months are October and November

with an average of 29.2 and 28.7 °C respectively, the coldest June and

July with a minimum average of 5.8 and 5.4 °C. The temperature almost

never drops below freezing. Most precipitation is recorded in December

with an average of 140 millimeters, the lowest in June and July with an

average of 3 and 6 millimeters. Because of the summer monsoon,

precipitation falls particularly in the period from mid-November to the

end of January; the annual average is 614 millimeters. However,

according to Innocent Pikirayi, a lecturer in history and archeology at

the University of Zimbabwe and familiar with the excavation site, the

rainfall for the area around the ruins is said to be higher, at 800 to

1000 millimeters a year, which would mean that agriculture was more

productive.

Vegetation

Mythical significance is ascribed to

vegetation in Greater Zimbabwe, particularly the mobola plum or muhacha

(Parinari curatellifolia), a golden plum family. Exotic introduced

plants that dominate the site today are the jacaranda (Jacaranda

mimosifolia), the eucalyptus and the lantana (Lantana camara). The ruins

have been overgrown over time by many specimens of red milkwood

(Mimusops zeyheri, from the genus Sapodaceae) and by a shrubby nettle

(Girardinia condensata).

Name

There are two theories about the origin of the word "Zimbabwe": The

first holds that the word is derived from Dzimba-dza-mabwe, translated

from the Karanga dialect of the Shona as "big house of stone" (dzimba =

the houses, mabwe = the stone) or also large stone house/stone palace

(the prefix z- marks a form of enlargement like the Italian suffix

-one). The Karanga-speaking Shona live around Great Zimbabwe; they

probably already inhabited the region when the city was built. The

second thesis postulates that Zimbabwe is a contracted form of

dzimba-hwe, meaning "honored houses" in the Shona Zezuru dialect, a term

used for the tombs and houses of the chiefs. The city was named after

the state of Zimbabwe (also Zimbabwe, formerly Southern Rhodesia).

The suffix "Great" is used to distinguish around 150 smaller ruins,

called "Zimbabwes", which are spread all over the country of Zimbabwe.

There are also about 100 Zimbabwes in Botswana, while the number of

Zimbabwes in Mozambique cannot yet be estimated.

Iron Age History

The area around Greater Zimbabwe was settled in the period from 300

to 650 AD. Rock paintings in Gokomere, about eight kilometers from

Masvingo, bear witness to this. The Gokomere/Ziwa tradition, with its

distinctive pottery and use of copper, is archaeologically associated

with the Iron Age. However, the Ziwa culture did not erect stone

buildings.

The first farming settlements in Mapungubwe on the

Limpopo date from around the year 900. The kingdom there existed between

1030 and 1290; with its decline due to changing climatic conditions, the

rise of Greater Zimbabwe began. On the plateau of Greater Zimbabwe,

hunter-gatherers, Iron Age agriculture and societies based on the

division of labor seem to have collided directly. Several states

emerged, sometimes one after the other, sometimes in parallel. Greater

Zimbabwe was the first center of the Mutapa Empire, whose power extended

to the coast and also north and south of present-day Zimbabwe. Khami, a

similarly large complex of walls seven kilometers west of Bulawayo,

first arose parallel to and later became the center of the Torwa Empire.

The Kingdom of Munhumutapa

Greater Zimbabwe is one of the oldest

stone structures south of the Sahara. Work began in the 11th century and

continued until the 15th century. There is strong evidence, but no

conclusive evidence, that the builders and residents of the city were

ancestors of the modern-day Shona, the Bantu people who make up about

eighty percent of the population of the present-day Republic of

Zimbabwe. The ceramics found are very similar to those of today.

However, since this culture did not develop writing, there is no

definitive proof. In the heyday, 20,000 people are said to have lived on

the site. Trade connections with Arabian coastal cities are

archaeologically proven by coin finds. However, in addition to numerous

objects from the heyday, pottery was also found in the area, which is

600 years older than the buildings. The country's wealth in gold was the

main reason for the commercial activities of Arab and Persian traders on

the southern tip of Africa and for the founding of Swahili cities in

Mozambique. Around 1450 Greater Zimbabwe was abandoned, probably because

the high concentration of population had exhausted the country. The

Mutapa state shifted its center north and lost its supremacy to the

Torwa state. The new center became its capital Khami for about 200

years.

Expeditions and Archaeological Research

Portuguese

expeditions and their reception

The Portuguese were the first

Europeans to establish a fort near Sofala at the beginning of the 16th

century and tried to get their hands on the South African gold trade.

They therefore sought Mwene Mutapa, the head of the Karanga kingdom. A

1506 letter from Diego de Alçacova to the Portuguese king states that in

Zunbahny, the capital of the Mwene Mutapa, "the king's houses ... are of

stone and mud, very large and on one level". In 1511, the Portuguese

explorer António Fernandes was the first European to visit the site. He

reported that "Embiere... was a fortress of the king of Menomotapa...

now of stone... without mortar." They also carried the legend to Europe

that the city was the home of the Queen of Sheba. In 1531, Vicente

Pegado, captain of the Portuguese garrison at Sofala, described Greater

Zimbabwe: “Amid the gold mines on the inland plain between the rivers

Limpopo and Zambesi stands a fortress built of astonishingly large

stones and without any mortar... This The structure is almost entirely

surrounded by hills on which similar structures made of stone without

mortar stand. One of these structures is a tower over 22 meters high.

The natives of the country call these structures Symbaoe, which means

courtyard in their language.” João de Barros published the report in

1552 in his work Décadas da Ásia. The information was based primarily on

descriptions by Swahili traders in Sofala.

The other mention of

stone buildings in this early period is found in Ethiopia Oriental,

published in 1609, by João dos Santos, who had been a missionary in the

country of Mwene Mutapa between 1586 and 1595. However, his statements

refer to stone buildings at the other end of the plain, opposite Great

Zimbabwe, on Mount Fura (today Mount Darwin) in Mashonaland:

“Some fragments of old walls and ancient ruins of stone and mortar

still stand on the top of this mountain. ... The natives ... affirm:

They had been told by their ancestors that these houses once represented

a trading post of the queen of Sheba. Large quantities of gold were

brought from here, which were transported by ship down the Cuamas rivers

to the Indian Ocean... According to others, the ruins come from a

settlement of King Solomon. . . . I can't vouch for it, but I do claim

that Mount Fura or Mount Afura could be the "land of Ophir" from whence

gold was brought to Jerusalem. This would give some credence to the

claim that the buildings in question were a trading post of King

Solomon.”

Shortly after dos Santos published his report, Diogo de

Couto, the successor of João de Barros, added in the work De Asia that

"it is supposed that ... the Queen of Sheba ... gold was mined in these

places ... the great stone buildings ...are called Simbaoe by the

Kaffirs, and they are strong fortifications." Although de Barros and dos

Santos recognized that they were engaging in questionable speculation,

the ideas they presented to the public so stimulated the imagination of

their recipients that their description two hundred Repeated for years

by Europe's finest geographers, it "acquired exotic accompaniments to

the same extent that speculation, which still had something to do with

conceptual thinking, turned into unquestioningly accepted dogma." Such

repetitions are found in the works the Italians Livio Sanuto (1588) and

Antonio Pigafetta (1591), the English Samuel Purchas (1614), John Speed

(1627), John Ogilby (1670), Peter Heylin (1656) and Olfert Dapper

(1668), and the French Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (1727) and

Charles Guillain.

The Expedition of Karl Mauch (1871)

After

Adam Renders (1822–after 1871) rediscovered the ruins while hunting in

1868 and claimed that “they could never have been built by blacks”, he

showed them to Karl Mauch (1837–1875) in 1871 on his fourth voyage to

southern Africa . In the years that followed, he equated it with the

biblical gold land Ophir, i.e. 2000 years earlier than today's

radiocarbon dating. He then passed the upper reaches of the Zambezi,

where he found a gold field (Kaiser Wilhelms field). In 1872 Mauch,

suffering from malaria, returned to Germany. He later questioned his own

Ophir Zimbabwe theory. The first publication by Alexander Merensky on

the Zimbabwe ruins appeared in Petermanns Nachrichten in Berlin in 1870.

In it he had summarized research reports.

The Expedition of James

Theodore Bent (1891)

When Cecil Rhodes conquered Mashonaland in

September 1890 with the help of the British South Africa Company, he

told local Bantu chiefs that he had come to see "the ancient temples

that once belonged to the white man". With William G. Neal, the head of

the Ancient Ruins Company, who had carried out illegal excavations on

this and other Iron Age sites in Zimbabwe and thereby destroyed

important findings, he commissioned James Theodore Bent (1852-1897) in

1891 to examine the ruins.

Bent's archaeological experience was

that he had traveled to the countries of the eastern Mediterranean and

the Persian Gulf in search of the origin of the Phoenicians. As an

archivist, he seems to have had a liking for archaeology, but no

archaeological training – and even less practical experience. In June

1891, Bent began excavating around the conical tower in the elliptical

structure and was very disappointed with the results. He later claimed

the ruins were built by either Phoenicians or Arabs. However, his

reports made the ruins known to a wider circle of English readers.

Much of the archaeological stratigraphy was destroyed during the

excavation by Bent's team, making it more difficult for later

archaeologists to determine the age of Greater Zimbabwe. Bent's team

eventually suggested that a "bastard" race of white immigrant males and

African women had constructed the structures. During Bent's research,

the ruins were surveyed by mining engineer Robert Swan. Based on his

plans, Swan developed his own theories, which assumed precise designs

based on the number pi for the larger sections of ruins. Based on Swan's

observations - and his claim that in the centers of the elliptical

arches there were now vanished altars that were aligned with the

solstices - the geologist Henry Schlichter later tried to calculate the

absolute age of the due to their natural variability. He came up with

1000 BC. However, since Swan's measurements were erroneous and made at

random points, this theoretical edifice proved untenable.

Peter

Garlake pointed out that in 1892 the British army officer, Major Sir

John Christopher Willoughby, "without any regard for casualties"

"gutted" three ruins in the valley, destroying the stratigraphic layers

within the north-west entrance to the Great Enclosure .

The

Expedition of Carl Peters (1899)

Carl Peters (1856-1918) led a

research trip to the Zambezi in 1899. He wanted to prove that the

biblical land of gold, Ophir, was in Southeast Africa. Since, in the

later judgment of the historian Joachim Zeller, he "represented National

Socialist positions, a rigid master's point of view and racist social

Darwinism", he could not imagine that the ruins of Greater Zimbabwe

could have African origins. He therefore looked for master builders from

the Middle East, in which he attributed a central role to the

Phoenicians. Peters was also interested in attracting shareholders to

his corporation, which was acquiring land in Portuguese Mozambique to

prospect for gold there. Peters enriched his Ophir theory with violent

defamation of black Africans and demanded the introduction of general

forced labor in the colonies.

The dig of Richard Nicklin Hall

(1902–1904)

The discovery of several gold finds in the 1890s at the

Dhlo Dhlo ruins led to the establishment of Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd.,

which systematically searched 50 ruins in Zimbabwe for gold finds, but

at the express wish of Cecil Rhodes excluded the ruins of Greater

Zimbabwe. The excavations yielded only 178 ounces of gold jewelry. The

company was disappointed by the other finds. The results of the campaign

were compiled into a book by local journalist Richard Nicklin Hall.

After several financial difficulties, Hall was appointed Curator of

Zimbabwe in 1902, charged with protecting Greater Zimbabwe under new

legislation. Due to two extensions, Hall performed this function for

almost two years instead of the originally planned six months. His

instructions consisted in carrying out "no scientific investigations"

but to devote oneself solely to "the preservation of the structure".

After Garlake, Hall didn't care what the purpose of his appointment was.

Instead, he had undocumented excavations carried out in the Great

Enclosure, the Hill Ruins, and much of the other valley ruins. Not only

were the trees, aerial roots and undergrowth and spoil heaps removed

from the Bent and Willoughby digs, but also 0.9-1.5 metres, in places

more than 3 metres, of stratified archaeological material. His

justification for what he himself called "a modern and timely work of

conservation" was that he was only clearing away the "filth and refuse

of the Kaffir people" with a view to uncovering the remains of the

"ancient" builders. After the criticism grew louder, especially in

scientific circles, the London office of the British South Africa

Company finally canceled the contract and dismissed Hall in May 1904.

The dig by David Randall-MacIver (1905/1906)

The first scientific

archaeological dig at the site was conducted in 1905/1906 by David

Randall-MacIver (1873-1945), a student and collaborator of Flinders

Petries. In the short time available to him, MacIver dug first in the

ruins of Injanga, Umtali, Dhlo Dhlo and Khami and then with this

experience in Greater Zimbabwe. He was the first to describe the

existence of find objects in "medieval Rhodesia" that can be assigned to

the Bantu. The absence of any artifacts of non-African origin led

Randall-MacIver to suspect that the constructions were carried out by

native Africans. In doing so, he set himself apart from earlier scholars

who wanted to attribute the buildings exclusively to Arab or Phoenician

traders.

The Caton-Thompson dig (1929)

In 1929, Gertrude

Caton-Thompson (1888–1985) investigated the "Ruins of Zimbabwe" on

behalf of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. At

this excavation Kathleen Kenyon (1906-1978), a British archaeologist,

collected her first archaeological experiences; she later taught at

University College, London. From the outset, Caton-Thompson limited

himself to narrowly defined basic questions of "Who?" and "Why?" and

tried to find dateable imported goods in stratigraphic contexts. To

achieve these goals, she selected a structure least damaged in previous

excavations that showed the architectural features of an original

structure as identified by Hall, and so whatever she found could only be

linked to the original builders. In terms of methodology, it was the

first and only regular area excavation. Their choice fell on the

so-called Maund Ruins, seen from the Great Enclosure at the far end of

the valley. She published the material she had obtained in seven working

weeks with all find lists and detailed descriptions of all finds, as

well as photos of most of the objects.

To show that their results

could be applied to all structures in Greater Zimbabwe, Caton-Thompson

had six search trenches dug outside the Great Enclosure and an adit dug

under the conical tower. After their excavations, "not a single point

remained which could not be reconciled with the statement that the Bantu

people were the builders and that the structure was of medieval origin."

Archaeologist Graham Connah and many historians believe that the city

had to be abandoned at the end of the Middle Ages because the permanent

overpopulation had led to an ecological catastrophe.

The Dig by

Roger Summers, Keith Robinson and Anthony Whitty (1958)

In 1958 a

major research program was launched by Roger Summers, Keith Robinson and

Anthony Whitty. The aim was not to raise the question of the builders

again, but to clarify the chronology of the pottery and the

archaeological finds. The goal was: "To set up a ceramic sequence in

Zimbabwe". In 1967, too, the chronology of ceramics was discussed again.

Radiocarbon dating (1950s and 1996)

In 1950 the first radiocarbon

dating was attempted using material from Greater Zimbabwe. These were

two stakes of tamboti (Spirostachys africana) wood discovered in the

same year in the Great Enclosure, supporting a drainage ditch through

the inner wall of the Parallel Passage, one of the oldest walls in the

structure. The samples returned the following results: "AD 590 ±120

years (C-613) and AD 700 ±90 years (C-917) and AD 710 ±80 years (GL-19)"

, the data has not yet been calibrated. Since Tamboti trees can live up

to 500 years, this increases the margin of error in C-14 dating by that

amount of time. It must also be considered whether the wood in the

findings found was used for the second or repeated time. Ultimately, the

dates say only that the walls were built at an unknown date after the

5th century AD. In 1952 the next samples were dated and gave "AD 535

±160 years, AD 606 ±16 years". It was the same species of wood as the

piles discovered in 1950 and the data was also uncalibrated. Further

dating was carried out on material from the 1958 excavation and resulted

in "AD 1100 ±40, AD 1260 ±45, AD 1280 ±45". The most recent dating was

made at Uppsala in 1996 on samples of mopane (Colophospermum mopane)

from the Great Enclosure wall and gave: '1115 ±73'.

architecture

General description of the ruins

The extant ruins

of the city cover an area of seven square kilometers and are divided

into three areas: the 27-metre-high Hill Complex, also known as the Hill

Fort or Acropolis, the Valley Complex, and the elliptical enclosure, the

so-called Great Enclosure (also called the Temple ). The walls of

Greater Zimbabwe are built of granite blocks and without mortar. The

Great Wall has a base of five meters, a height of nine meters and a

total length of 244 meters. The dry stone walls even lack corner joints.

And, despite the name, they have never had roofs. They were stone

enclosures. In the courtyards thus enclosed stood huts and houses made

of mud and wood. Next to the four-meter-wide stairway to the Acropolis,

carved into the rock, the monoliths could have served astronomical

purposes.

mountain ruins

In the 19th century, visitors

repeatedly gave the mountain ruins the misleading name "Acropolis". At

first only the hill enclosure seems to have been named dzimbahwe. The

hill stretches 80 meters above the so-called Valley, on the south side

it is formed by a 30 meter high and 100 meter long cliff. The steepest

and shortest way to the top is the Cliff Ascent. On the high plateau to

the west is the eight meter high and five meter thick wall of the

western enclosure. Probably every two meters towers alternated with

stone columns on the top of the wall. The only two columns and the four

towers that exist today were reconstructed in 1916. The wall itself is

original, but part of the exterior had to be reconstructed due to

damage; the reconstruction is easy to see.

The original entrance

to the western enclosure is near the edge of the steep rock step and is

now walled up for safety. The current entrance is part of the wall

reconstruction of 1916. The western enclosure, the main living area on

the hill ruin, was continuously inhabited for 300 years. Remains of the

former huts covered the interior of the enclosure up to eight meters

deep. During safety work in 1915, a large part of it was thrown down the

rock face. Nevertheless, the original inspection horizons are still

visible in many areas. A similar "parallel passage" seems to have been

intended with the help of internal walls, as in the Great Enclosure in

the Valley. The southern wall stands directly on the cliff edge and was

decorated with columns. The northern and eastern walls are formed by

protruding rocks, over which the walls only had to be built by hand in

places, as the builders seem to have sought to involve nature in their

construction. In the north-east corner of the mountain plateau, the

so-called balcony is about ten meters above the enclosure. Various

columns made of granite and soapstone stood in this area until the end

of the 19th century, the largest of which was four meters high. One of

the Zimbabwe birds was recovered from the rubble in this balcony.

Large enclosure with parallel passage and conical tower

The Great

Enclosure was referred to as Imba Huru (Big House) by the locals in the

19th century. The current entrance through the Great Wall is a 1914

reconstruction placed in an inaccurate location. The wall is 255 meters

long and the weight of the million or so stones used is given as 15,000

tons. While the north-western part consists of relatively unornate

stones, the north-eastern part is expertly crafted, eleven meters high

and four meters thick at the top and up to six meters at the base. The

wall in the north-western area is of the poorest quality and is only

half as high and half as thick as in the other sections. Particularly

hard diorite was used to work the stones. The interior of the Great

Enclosure consists of several parts, starting with Enclosure #1, the

central area, the original outer wall, the conical tower and the narrow

tower, and the Dakha Platforms. Just north of the central area is

Enclosure #1, a simple circular wall and the earliest building in the

Great Enclosure. Inside were once huts of a household.

The so-called Parallel Passage connects to Enclosure No. 15 in the

north. It is formed from the present outer wall of the Great Enclosure

and the original outer wall built shortly after Enclosure #1. The inner

wall is about a century older than the outer. Archaeologist and former

curator of the site, Peter Garlake, theorized that the privacy of the

royal family, who lived behind the original wall, was at stake.

Privileged guests admitted into the enclosure surrounding the conical

tower could thus be admitted into the Great Enclosure and yet remain

outside the royal quarters. The passage is over 70 meters long and

almost everywhere only 0.8 meters wide. Between the passage and the

tower enclosure there are a series of platforms at different heights.

Until 1891 all entrances to the tower enclosure were blocked with

well-worked stones.

The conical stone tower is still ten meters

high today. Its diameter is five meters at the base and about two meters

at the top. Originally there was a three-line ornament on the upper

edge, which consisted of stones rotated by 45°, thus forming a series of

triangles in a zigzag pattern. For a long time it was assumed that there

was a secret treasury inside the tower. In 1929, the tower was partially

tunneled by archaeologists and it turned out to be solid and built

directly on the ground. The original construction and appearance of the

spire is unknown. Tower structures of unexplored function were also

built in Oman and Sardinia (Nuraghe), for example.

enclosures in

the valley

In addition to the Great Enclosure, there are a number of

smaller enclosures: Outspan Ruin, Camp Ruin, Hilltop Ruin, Ruin #1,

Posselt Ruin, Render Ruin, Mauch Ruin, Philips Ruin , the Maund Ruins

and the East Ruins.

finds

Six of the eight stone sculptures

were found in the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins, which the

population apparently regarded as a sacred place. These Zimbabwe birds

are stone figures about 0.4 meters high that were placed on top of

pillars, reaching a height of one meter. Seven of the stone birds are

complete. Soft soapstone was used as the material. What is striking

about the birds is how unrealistic they are portrayed, for example how

thick the legs are or how bulky the body.

Some of the birds were

returned to Zimbabwe in 2003 after having been in Germany for almost 100

years. Today, the birds are a national symbol that is also found in the

state coat of arms and the national flag of Zimbabwe.

The first

bird was removed from the Philips ruins by Richard Hall in 1903. The

figure is 28 centimeters high, but measures 1.64 meters with the foot.

It is 23 centimeters deep and 6 centimeters thick. It is the most famous

of the eight birds, having become the model for depiction on the flag

and coat of arms of Zimbabwe.

The second bird is one of the

earliest artifacts removed from the ruins, having been taken from the

east wall of the hill ruins by Willi Posselt as early as 1889 and

probably sold to Cecil Rhodes. Because the bird was too big, Posselt

separated it from the column. The bird is 32 centimeters high with bent

legs and 12 centimeters wide at the thickest point. He is adorned with a

diamond patterned band around his neck.

The third, comparatively

roughly designed bird was removed from the east enclosure of the

mountain ruins by Bent. The figure is 43 centimeters high and 22

centimeters deep. The beak is broken off, but it appears to have been

the beak pointing farthest into the sky of all eight figures. The bird

stands on an implied wooden ring (like bird 7).

The fourth bird

was also removed by Bent from the eastern enclosure of the mountain

ruins. It measures 1.75 meters with the support column, and the bird is

only 34 centimeters high. At its thickest point it is 10 centimeters

wide. The eyes are marked by small humps. The tail is clearly spotted.

The fifth bird is also from the eastern enclosure of the hill ruins

and was removed by Bent in 1891. It is 1.73 meters high with the column,

the figure alone is 33 centimeters high and 9 centimeters wide. The beak

is also broken off, the eyes are knobbs, the wings are indicated but

smooth. Diamond patterns are indicated on the back. The tail is also

clearly spotted.

The sixth bird was also removed by Bent from the

eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins. It is 1.53 meters high with the

support column. The bird figure itself is 33 centimeters high and 10

centimeters wide. It has diamond patterns on its back similar to Birds 2

and 5.

From the seventh bird only the lower 20 centimeters are preserved. It

could have been the smallest of the eight figures and, like Bird 3,

stands on an indicated wooden ring. He was standing in the eastern

enclosure of the mountain ruins and was removed by Bent. The tail is

decorated with a herringbone pattern.

The broken specimen of the

eighth bird was removed from the mountain ruins by Richard Hall in 1902.

He is said to have stood on the so-called balcony, from which the

western enclosure of the mountain ruins can be overlooked. Hall found

only the top part of the figurine, sold it to Cecil Rhodes, who already

owned the bottom part. In 1906, the missionary Axenfeld brought the

figure to the Ethnological Museum in Berlin.

The Royal Treasure

A collection of objects referred to as royal hoards was found in

Enclosure No. 12 in the so-called Renders Ruins north of the Great

Enclosure in 1902 without observing or documenting the site or

stratigraphy. Around 100 kilograms of iron picks with traditional

patterns, but also narrow iron picks or adzes (adzes), axes and chisels.

Furthermore, an iron gong with narrow iron striking devices, two large

spearheads and over 20 kilograms of twisted wire. The find also

contained copper and bronze wires, some of which had already been

processed into jewellery. Another important find were tens of thousands

of small glass beads, probably from India, and 13th-century Chinese

pottery covered with celadon.

Other finds

Only a few finds

from the early excavations can be seen in the on-site museum. This

includes four bronze spears with separate blades, which seem very

impractical and were probably intended as a gift. Gongs and their batons

have also been preserved, as well as iron tongs, drawing boards and

molds used by the metalworkers in the Great Enclosure. Other finds

include Arabic coins and glassware. Finds discovered by early European

settlers in the hills surrounding the ruins include wooden bowls

decorated with crocodile patterns, as well as Ming Dynasty Chinese

pottery and Assam jewelry. It is not known with which Chinese fleets the

pottery reached the East African coast and from there on the trade

routes to Greater Zimbabwe.

political significance

The ruins

are a very important archeological site of southern Africa. Initially,

the evaluations were carried out by the Rhodesian Ancient Ruins Ltd.

aggravated, a commercial group of treasure hunters who had been granted

official digging rights. Subsequent excavations, particularly by R.N.

Hall, destroyed many traces of the Shona culture as the researchers, of

European origin, wanted to prove that the construction of ancient

Zimbabwe was not of black African origin. During British rule in

Rhodesia, as Zimbabwe was called until the black majority took power,

the indigenous African origin of the ruins was always disputed. In

addition to the Phoenicians, other exclusively light-skinned people (or

at least white men) were also referred to as founders.

In 1970,

archaeologists Roger Summers, National Museum employee (1947-1970), and

Peter Garlake (1934-2011), Rhodesian monument conservator (1964-1970),

left what was then Rhodesia because they wanted to continue working

under the white minority government of Ian Smith could no longer

reconcile with their scientific working methods. In 1978, Garlake became

Lecturer in Anthropology at University College, London University.

The ruins of Greater Zimbabwe have been featured on Zimbabwe's

national coat of arms since 1981.

Robert Mugabe cultivated a

personality cult based on African traditions and traced his origins back

to the kings of Greater Zimbabwe. That's why he was dubbed Our King.

Poems and hymns of praise, which had to be learned in schools,

celebrated his services to the country and his heroic deeds during the

war of liberation. He was also bestowed with numerous honorary titles

formerly borne by Shona kings.

One of the local ethnic groups,

more specifically the Lemba, has been linked to Semitic groups through

genetic comparisons.

infrastructure and tourism

Tourism development

The entire area

is managed by the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe, with

Godfrey Mahachi as the site manager. The individual buildings are

accessible by paths and explained in several places by boards. A guest

house run by the national park administration and a campsite are

available to visitors. Despite the difficult political and economic

situation, the site continues to be visited by foreign guests.

However, after the country reform program in 2000, tourism in Zimbabwe

has been steadily declining. After increasing during the 1990s, with 1.4

million tourists in 1999, the number of visitors fell by 75 percent in

December 2000, less than 20 percent of the hotel rooms were occupied in

the same year. The total number of visitors for Zimbabwe in 2008 was

223,000 tourists. With the ruins of Greater Zimbabwe being the second

most visited main attraction in Zimbabwe after the Victoria Falls, this

has a particular impact on the local tourism industry. Local tourists

have been deterred from visiting by hyperinflation and a lack of basic

services, while foreign visitors have been discouraged by the unstable

political situation. With tourist visits falling by over 70 percent in

2001, more than 12,000 people lost their jobs. According to information

from the Federal Foreign Office, Zimbabwe has "almost completely lost

the former charm of a pleasant tourist and travel country with good

infrastructure."

By the year 2000, arriving visitors spent 2.5

hours touring the facility. The most visited spot was the Great

Enclosure, followed by the Gift Shop and then the Hill complex. Within

the Great Enclosure, the conical tower was the most frequently visited.

As a result of political developments in Zimbabwe, visitor numbers fell

from 120,000 in 1999 to 15,442 in 2008. For 2010, 30,000 visitors were

expected. List of paying visitors:

1980: 42,632

1981: 56,027

1989: 84,960

1990: 87,820

1991: 88,296

1992: 70,720

1993:

102,877

1994: 111,649

1995: 120,993

1996: 91,652

1997:

88,122

1998: 153,343

1999: 120,000

2006: 20,000

2007: 27,587

2008: 15,442

2010: about 30,000

2011: 49,323

2013: 55,170

2014: 58,180

2017: 61,000

2018: 72,284

2019: 45,359

2020:

11,952

Greater Zimbabwe receives operational funding from the US

government for the security forces and part of the museum. Further

funding is provided by the Culture Fund of the Swedish International

Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for the development of the site.

The National Public Investment Fund, which is based on a 50-50 rule, is

helping to build the infrastructure. Unesco occasionally provided funds

in the 1990s, for example for firefighting.

Museum Shona village

To the east of the ruins, a museum model of a 19th-century Shona village

was erected in 1986 as an additional attraction for tourists. However,

the representation of the components, the staff and the activities of

village life were described as not very authentic. In particular, the

use of modern tools in the demonstration of traditional crafts and the

modern clothing were criticized. Some researchers describe visitor

confusion and negatively assess the impact on the World Heritage site.

visitors to the ruins

The ruins have been the destination of

travelers ever since they were made famous by Mauch and Bent. Cecil

Rhodes visited the ruins as early as 1890. Queen Elizabeth II visited

the site twice, first on a three-month trip to South Africa in April

1947 with her father King George VI, her mother Elizabeth and her sister

Princess Margaret, and again in October 1991. On July 12, 1993, Princess

Diana visited Greater Zimbabwe and on May 20, 1997, Nelson Mandela.

transport connection

There are many local bus services between

the ruins and the bus terminal in Masvingo. From the ruin site there are

also direct bus connections (coaches) to Bulawayo or Harare. The nearest

international airports are Harare Airport to the north and Johannesburg

Airport to the south.

Miscellaneous

The ruins featured on the

Z$50 bill from the introduction of Zimbabwe's currency notes after

independence in 1980 until the currency was suspended in 2008, but which

has hardly been used since 2000 due to hyperinflation. One of the

Zimbabwe birds was the motif on the 1 cent coin.

Furthermore, a Z$1

stamp was issued on the occasion of the inclusion of the ruins in the

World Heritage List in 1986, on which the Great Enclosure is depicted.

Another stamp, this time featuring the conical tower and the bird of

Zimbabwe, was issued in 2005.