The traditional culture of the peoples of Russia, in the form in which it was formed by the time of its ethnographic study (that is, approximately by the 2nd half of the 19th century), reflects their complex history in constant interaction with each other, in different geographical, natural and economic conditions. On the territory of Russia, several historical and cultural zones with a characteristic economic and cultural type of the peoples living there.

National Costume of the Peoples of

Russia

Tales of the Peoples of Russia

A

Altai Culture

B

Bashkir Culture

Buryat Culture

C

Circassian culture (5: 2 cat., 3 p.)

Chechen culture (7: 3 cat.,

4 p.)

Chuvash culture (10: 7 cat., 3 p.)

Cossack culture

D

Don Cossacks in Culture

I

Ingush Culture

K

Karaite culture

Culture of the Komi peoples

Kumyk culture

M

Mari Culture

Mordovian culture

H

Nenets culture

O

Ossetian culture (18: 11 cat., 7 p.)

R

Russian folk culture

(19: 15 cat., 4 p.)

T

Tatar culture (13: 11 cat., 2 p.)

Tuvan culture (13: 3 cat., 10 p.)

U

Udmurt folk culture (4:

4 cat.)

Origin and development of the Russian people. The historical roots of

Russians go back to the East Slavic population of Kievan Rus. With the

collapse of the Old Russian state, and especially after the Mongol

invasion of the 13th century. the formation of new ethnic ties began.

The core of the Russian people was the population, united in the

14th-16th centuries. Grand Duchy of Moscow. The center of its territory

- the Volga-Oka interfluve - from the 9th century. settled east. Slavs

in three streams: Novgorod Slovenes from the northwest, Smolensk

Krivichi from the west and Vyatichi from the southwest. This feature of

the settlement explains the border position of this territory between

the northern, southern and western Russian regions. Settling in the

interfluve, the Slavs assimilated the local Finno-Ugric (Meryu, Muroma,

Meshchera) and Baltic (golyad) population. Joining the beginning 16th

century North-Western Russia, the Volga lands and the Urals to the Grand

Duchy of Moscow and the further expansion of the state, which took place

in the struggle against the Tatar khanates, led to the final formation

of the ethnic territory of the Russian people and its historical,

cultural and dialect regions. Russian colonization was directed in the

14th-16th centuries. from the center to the European North (regions that

were the object of Novgorod and Rostov colonization in the 12th–13th

centuries), in the 16th–17th centuries. - in the Vyatka and Kama-Pechora

regions, in the black earth regions that were deserted after the Tatar

invasion (“Wild Field”), the forest-steppe and steppe regions of the

Middle and Lower Volga, Don and Azov regions, Siberia was mastered by

people from Pomorye. In the 18th century Russians penetrate the South

Urals and the North Caucasus. In the 18th and 19th centuries and

especially after the reforms of the 1860s. new streams of Russian

settlers rushed to Siberia, mainly. from the central and southern

regions of European Russia; to con. 19th century Russian population

appears in Central Asia. Migration from Central Russia to the outskirts

intensified especially during the existence of the USSR.

Ethnographic groups of the Russian people. The complex ethnic history of

the Russian people led to the formation of historical and cultural zones

on its territory with characteristic dialectal, cultural and

anthropological differences between their populations.

First of

all, on the territory of European Russia, the North Russian and South

Russian zones and the middle strip between them are distinguished.

The North Russian historical and cultural zone occupied the

territory from Volkhov in the west to Mezen in the east and from the

White Sea coast in the north to the upper reaches of the Volga in the

south (Karelia, Novgorod, Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Yaroslavl, Kostroma

provinces, the north of Tver and Nizhny Novgorod provinces). This group

of Russians is characterized by a "surrounding" dialect, small-yard

rural settlements, united in "nests", plow as the main. a type of arable

implement, a hut on a high basement connected to a household yard

(“house-yard”), a sarafan complex of a women's folk costume, a special

plot ornament in embroidery and painting, epics and lingering songs and

lamentations in oral art. Of the territorial groups of the Russian

North, the Pomors are the most famous - the Russian population of the

White Sea (from Onega to Kemi) and the Barents coasts, which has

developed a special cultural and economic type based on fishing and fur

hunting, shipbuilding, navigation and trade.

The South Russian

historical and cultural zone occupied the territory from the Desna in

the west to the upper Khopra in the east and from the Oka in the north

to the middle Don in the south (the south of the Ryazan, Penza, Kaluga

provinces, Tula, Tambov, Voronezh, Bryansk, Kursk and Oryol provinces).

It is characterized by a "kakay" dialect, multi-yard rural settlements,

a land-based log house, in the south - plastered with clay or an adobe

dwelling (hut), a women's costume with a pony skirt, polychrome

geometric ornament in clothes. This group of Russians has a more

variegated ethnocultural composition than the northern one, which is

associated with the peculiarities of the settlement of the Black Earth

region by people from various regions of Central Russia. Of the

territorial groups of southern Russians, the most famous are the Polekhs

in the Kaluga-Bryansk Polissya - the descendants of the most ancient

population of the forest belt, close in culture to the Belarusians and

Lithuanians; goryuny in Putivl u. Kursk province. - the descendants of

the ancient northerners from the resettlement waves of the 16th-17th

centuries, who had a cultural similarity with the Ukrainians and

Belarusians; stellate sturgeon in the Kursk province. - the descendants

of the military service population of the Kursk border.

The

population of the middle zone - in the interfluve of the Oka and Volga

(Moscow, Vladimir, Tver provinces, the north of Kaluga, Ryazan and Penza

provinces and part of the Nizhny Novgorod provinces) - a mixed type of

culture was formed: a dwelling on a basement of medium height, a sarafan

complex of a women's costume, dialects, in the north - with “okay”, in

the south - with “kaka” pronunciation. Territorial groups were also

distinguished here: the Meshchers of the left-bank Zaochi - the

descendants of the Russified Finno-Ugric tribe; Korels - a group of

people who moved to Medynsky district. Kaluga province. Tver Karelians,

etc.

The Russian outlying territories were distinguished by their

originality. Residents of Western Russian regions - along the river.

Velikaya, in the upper reaches of the Dnieper and the Western Dvina

(Pskov, Smolensk, west of the Tver provinces) - in terms of culture they

were close to the Belarusians, in the north “okaying” dialects were

common, in the south - “okaying” dialects; the Russians of the Urals

(Vyatka, Perm, part of the Orenburg province) combined features of the

northern and central Russian culture; the Russians of the Middle Volga

region were approaching in culture with the indigenous peoples of the

Volga region; Russians in the southeast - from Khopra to the Kuban and

Terek, in the territory of the Don Army Region, in the Kuban and Terek

regions and in the east of Novorossia - were connected by origin with

southern Russians and Ukrainians. A special ethno-class community, which

included, in addition to Russians, other ethnic components (Ukrainian,

Turkic, etc.), was represented by the Cossacks, of which the Don, Kuban,

Terek, Yaik are the most famous, in Siberia - Transbaikal, Amur, Ussuri,

etc.; a group of Ural Cossacks who settled in the 19th century. on the

Amu Darya and Syr Darya, formed a special group of the Russian

population of Central Asia.

The Russian old-timer population of

Siberia ("Siberians") - the descendants of the initial wave of Russian

colonization - retained the North Russian culture and differed from the

numerically predominant later settlers from the central and southern

provinces ("new settlers", "Russian"). Among it were various Old

Believer groups (“masons” of Bukhtarma, “Poles” of Kolyvan, “Semei” of

Transbaikalia) and groups of mestizo origin: gurans (descendants of

Russian men and Tungus women) and Kudara (descendants of Russians and

Buryats of Transbaikalia), Amgins, Anadyrs, Gizhigins, Kamchadals,

Kolyma residents of the North-East of Siberia - the descendants of the

mixing of Russians with Yakuts, Evenks, Yukaghirs, Koryaks, etc.;

isolated groups were Russian-Ustyintsy in the village. Russian Mouth on

the Indigirka and the Markovites in the village. Markovka at the mouth

of the Anadyr.

The main occupation of most Russian groups is agriculture. The fallow system (two-field and three-field) developed in the 12th-13th centuries, along with it in the forest areas until the 19th century. slash-and-burn agriculture was preserved; in the south in the steppe regions and in Siberia, the fallow-fallow system spread. The main grain crop was winter rye, in the south. in the forest-steppe regions - also millet and wheat, in the northern regions - barley and oats. The main arable tool in the Non-Chernozem region is a two-pronged plow, from the 14th century. - its improved versions: three-toothed, with a relay police, roe deer, wheeled vehicle in Siberia, etc. In the steppe and forest-steppe regions, a Ukrainian-type plow was common (with a blade, a cutter and a wheeled limber), in the Urals - a Tatar wheeled plow-saban. Primitive arable implements-ralas were also known. The main draft animal was the "suffering horse", in the south - the ox. They harvested bread with sickles, in the south - with scythes, threshed with flails; from the 14th century special buildings for drying (barns, rigs) and threshing (threshing floor) of bread are distributed. Grain was ground using hand or water mills, from the 17th century. windmills ("German") mills spread. Animal husbandry traditionally had an auxiliary value, in the 19th century. first, in the landowners, then in the peasant farms, areas of commercial dairy farming were formed, of which the specialized production of butter in the Vologda region is especially famous.

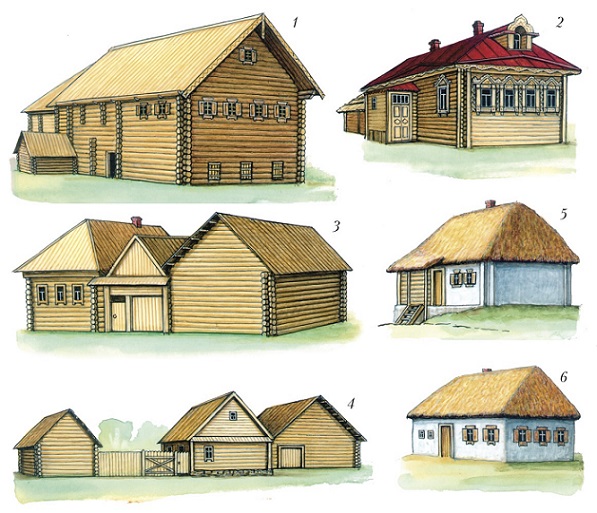

Russian peasant dwelling: 1 - North Russian house-yard; 2 - central regions: single-row connection; 3 - central regions: two-row communication; 4 - western regions; 5 - southern regions; 6 - Kuban.

Along with agriculture, forestry, salt-making and iron-working, fishing, hunting and shipbuilding developed.

Rural settlements were originally called villages, united into rural

communities. Already in the ancient Slavic era, community centers were

distinguished, often fortified. From the 10th c. communities (pogosts,

volosts) were grouped around administrative-taxable, later also

religious centers-pogosts. Over time, the term "pogost" was replaced by

the term "village", and small rural settlements were called villages

(since the 14th century); the name "pogost" is retained by the church

estate with a cemetery. With the spread of feudal landownership

(especially since the 16th century), settlements began to be enlarged;

It was common for small villages to move into large villages. At the

same time, new one-yard, originally seasonal, settlements continued to

emerge - zaimkas, repairs, etc., which eventually grew into villages.

The initial layout of a traditional Russian rural settlement is

scattered, then ordinary (courtyards are placed along a river, lake

shore or road) and finally street, street-block, street-radial.

Dwelling. Initially, the main a type of East Slavic dwelling was a

semi-dugout with log or frame walls, in the north - a ground log

house-hut, in the 10-13 centuries. became the dominant form of

construction. At the same time, two-chamber dwellings appeared, divided

into a hut and a canopy. By the 17th century spread three-chamber

houses, which had a hut, a cage and a canopy between them. By the

18th–19th centuries formed the main regional variants of the Russian

hut.

The northern version of the hut (“house-yard”) was a

building on a high (1.5–2 m) basement (usually serving as a pantry),

connected by a passage with a utility yard, on the lower floor of which

there was a barn, on the upper (on poveti), as a rule, household

equipment, hay were stored, sometimes unheated living quarters (cages,

burners) were arranged here. The hut and courtyard were connected by one

gable male roof (single-row connection). The hut faced the street, the

facade usually had three windows and carved decor. The estate included,

in addition to the hut, a barn, a bathhouse, etc.

The huts of the

Central Russian regions, the Upper and Middle Volga regions had a

smaller size and basement height than the North Russian ones. The

courtyard was attached to the hut in the form of a single-row or

double-row (to the side wall of the hut, often under a separate roof)

connection. The facade carving of the Central Russian huts was even

richer than that of the North Russian ones: the platbands were decorated

with a trihedral-notched ornament; in the 1840s in the Upper Volga

region (due to the high development of outhouse carpentry here), a

special style of carving was formed with high relief and the use of

plant and zoomorphic motifs (“ship carving”). In con. 19th century

propyl carving with a jigsaw is distributed.

The South Russian

dwelling (hut) did not have a basement, sometimes it was plastered with

clay or was completely adobe (due to a lack of timber), placed with a

long side to the street, covered with a hipped roof. The yard was open,

with outbuildings around the perimeter, and went out onto the street

with boarded gates. In the steppe zone, open courtyards with a free

arrangement of buildings were common. Baths, unlike the northern and

central Russian regions, were not built.

Later, wealthy peasants

everywhere had houses (five-walls, crosses), in which, in addition to

the main, heated room-hut, there was one or more. front rooms (rooms),

and, finally, multi-room or two-story houses.

Characteristic for

all Russians, as well as for other east. Slavs and many of their

neighbors, a Russian stove was a feature of the hut - a large adobe,

later - a brick structure for universal purposes (for heating, cooking,

sleeping, and where there were no separate baths, for washing, etc.).

The location of the furnace determined the internal layout of the main.

the premises of the dwelling, which, in fact, was called the hut. Its

traditional local variants have developed. In the north, the stove was

placed near the entrance and turned with its mouth to the facade wall,

the red corner (the front corner with icons) was in the corner opposite

from the stove, next to the end wall, overlooking the street with three

windows. The opposite side of the hut from the red corner, next to the

stove (baby kut), was considered the female half, had an economic

purpose, and was sometimes separated by a partition; near the stove they

arranged an entrance to the underground, fenced off with boards

(golbets); golbtsy were often decorated with paintings. Benches and

shelves were cut into the walls around the perimeter, and upstairs in

the back half of the hut there were beds on which they slept. In the

Western Russian regions, the stove was also placed at the entrance, but

its mouth turned to the entrance, one was cut through in the end wall,

and two windows in the side wall overlooking the courtyard. The main

difference between the South Russian layout and the North and West

Russian ones: the stove was placed in the corner opposite from the

entrance (in the east of the region - the mouth to the entrance, in the

west - to the side wall), and the red corner was arranged on the side of

the entrance; the hut faced the street with a side wall (opposite from

the stove) with two windows.

Of great importance was the

decorative design of the interior of the house - carving and painting on

wood (shelves, benches, golbets, spinning wheels), patterned and

embroidered fabrics (towels in the red corner, rugs, etc.).

Traditional Russian clothes were made from homespun linen, hemp and

woolen fabrics.

The main men's clothing is trousers and a

tunic-shaped (without seams on the shoulders) shirt, tied with a belt,

originally with a collar slit in the middle; OK. 15th–16th centuries a

type of kosovorotka with a slit on the left was formed, called the

Russian shirt, in contrast to the Ukrainian and Belarusian ones, which

retained a straight slit.

Their local variants have developed in women's clothing. The ancient

type of women's costume of Russians, as well as other peoples of Eastern

Europe, is a long shirt tied with a belt (later, the East Slavic

peoples, unlike their neighbors, developed a type of women's shirt with

sewn-in shoulder, richly ornamented inserts - polyks) and an unstitched

skirt. OK. 16th century a new type of women's clothing appears - a

sundress (sayan, sukman, fur coat). Initially, a sarafan was called the

outer men's swing clothing, then this name was transferred to women's

outer deaf clothes without sleeves - first in the costume of noble women

and townswomen, then - northern and Central Russian peasant women. Two

mains were known. type of sundress: northern, or Novgorod (sukman,

shushpan, shushun), - oblique and Central Russian, or Moscow (Sayan, fur

coat, round), - straight pleated on straps. They put on a short jacket

with or without sleeves (shower warmer) on top.

In the south, an

older type of women's clothing with an unsewn pony skirt has been

preserved. The simplest type of poneva is a “different regiment”,

covering the body from the sides and back. The floors diverging in front

were often worn tucked up behind the belt, so they were decorated not

from the face, but from the wrong side. Usually ponyova was sewn from

three woolen panels, usually of a checkered pattern (the size of the

cage and colors differed in each village or group of villages).

Sometimes a seam made of plain canvas or cotton fabric was inserted in

front - such a ponywa was sewn along all the seams and was called

"solid". Ponyovs were worn with a shirt and an upper deaf or swinging

jacket, tunic-shaped cut, with sleeves or without sleeves (top, bib,

nasov, shushun, shushpan, cloth, wire rod), sometimes with a long apron

(zapan, curtain). Ponyovs, tops, aprons were painted in red, black,

blue, yellow, embroidered with braid, galloon. The Western Russian

women's costume was close to the Belarusian and Ukrainian ones and

consisted of a shirt and a pony, close to the Ukrainian pakhta or

Belarusian andarak.

Men's hats - felted and felted, in winter -

fur. Strictly distinguished girls' and women's hats. It was obligatory

for a married woman to cover her hair completely. The basis of the

female headdress was a cap - soft (povoynik, bodice, head, etc.) or on a

solid basis (kika, kokoshnik, etc.) with an elegant headband or band,

sometimes of a peculiar shape (horned, saddle-shaped, spade-shaped,

etc.); in the south, the solid base of the kiki was covered with an

elegant cloth cover-magpie (often the entire headdress was called a

magpie), supplemented by a nape, forehead, side pendants, etc. Over the

cap, the head was often covered or tied with an elegant scarf (povoy,

ubrus, veil).

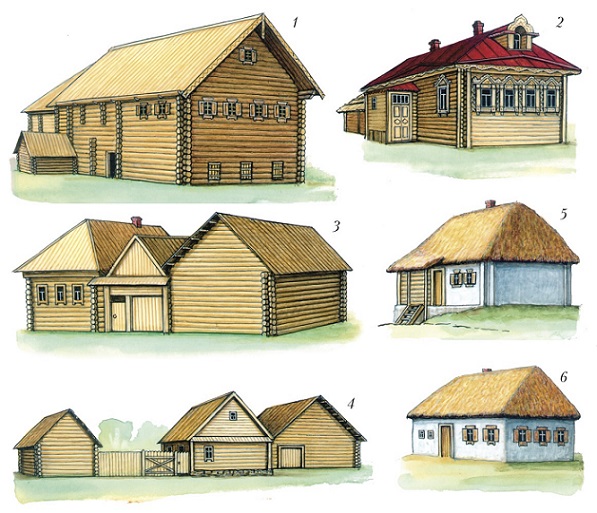

Women's hats: 1 - a woman in a kokoshnik (Vologda province); 2 - a woman in a kokoshnik and a headscarf (Olonets province); 3 - a woman in a horned kick (Ryazan province.).

It was typical for a girl's dress not to hide her hair, so the girl's

dress looked like a crown with an open top (bandages, corunas, etc.) or

a fabric bandage; girls braided their hair in one or two braids or

walked with their hair loose.

Elegant clothes were richly

decorated with embroidery, lace, galloon, pearls; women wore a lot of

jewelry.

Both men and women wore various types of outer garments:

kaftans, okhabni, fur coats, ferezis, fur coats, zhupans, zipuns; women

also wore padded jackets, etc.; in the cities, and then in the villages,

a type of women's clothing with a skirt and a jacket (“couple”) and

other forms of Western European clothing spread.

The traditional

shoes were woven bast shoes worn with onuch windings, or primitive

leather pistons, in winter - felted shoes (felt boots, wire rods,

kengi); felted shoes with high tops began to be produced from the

beginning. 19th century in the Nizhny Novgorod province. Leather boots

were rich or festive footwear.

The basis of traditional Russian food was cereals, from which they baked bread and cooked porridge. Ritual and festive dishes (loaf, Easter cake, pancakes, kutia, etc.), as well as drinks (beer, kvass) had a bread and cereal basis. Legumes (in the main peas) were traditionally attributed to bread food, cabbage and turnips were the main vegetables. The consumption of meat was limited, especially under the influence of religious prohibitions: the consumption of many types of game, equids, etc. was condemned. Fish food was especially widespread among the inhabitants of the banks of large rivers and sowing. seas. The peoples of the North and Siberia also adopted special ways of preparing fish: freezing (stroganina), pickling, and drying (yukola). From the culture of the Turkic peoples, new flour dishes penetrated into Russian cuisine - stews (salamat, burda), dough fried in oil (doughnuts, shavings, brushwood, etc.). One of the chap. Russian dishes in Siberia became dumplings.

The traditional religion of Russians is Orthodoxy (see Art.

Religions). Russian calendar rites are associated with church holidays.

The most developed are the rites of the winter solstice (Svyatki), timed

to coincide with Christmas (December 25 according to the Julian

calendar) and Epiphany (January 6), and the end of winter (Shrovetide,

Cheese Week), preceding Great Lent. Christmas time was accompanied by

caroling, making ritual cookies (goes), starting from St. Basil's Day

(January 1) - fortune-telling and disguise. They also dressed up on

Maslenitsa, rode in a sleigh, from the mountains, on a swing, baked

pancakes and pancakes, on the last day they organized a procession with

a stuffed Maslenitsa, which was burned or torn to pieces. And the

Christmas and Shrovetide rites, condemned by the Church, ended with the

rites of purification at Baptism and Forgiveness Sunday. Spring rites -

the feast of the Forty Martyrs (Magpies, March 9), the Annunciation

(March 25), the day of St. George (Egoriy Veshny, April 23), etc. - were

accompanied by singing spring songs, baking buns in the form of birds

(larks, rooks, black grouse), etc. Ritual food was prepared for Easter

(colored eggs, curd Easter, rich bread-cake) ; going from house to house

with ritual songs (vynoshnik), games, youth meetings were resumed, from

that day round dances began, from the eighth day of Easter (Fomin's

week, Krasnaya Gorka) - weddings. The rites of the summer solstice fell

on the Trinity preceding it (Semik) or the subsequent (Rusal) week, or

on Ivan's Day (Ivan Kupala, June 24). Trinity rites were accompanied by

rituals with birch trees or branches, mermaid rites were accompanied by

dressing up, the ritual of “expelling a mermaid” with the destruction of

a doll (Mermaid), Kupala rites were accompanied by dousing with water,

fortune-telling, and also rituals with a doll (Kupala, or Kostroma). The

summer holidays ended on Peter's Day (June 29). In the spring (before

Maslenitsa and after Easter), in the summer (before the Trinity) and at

the beginning of winter (before the day of St. Demetrius of

Thessalonica, October 26), special memorial days were arranged (Parental

Saturdays, Radonitsa).

Solemnly celebrated local holidays -

temple, congress, village brethren (sypki, beer holidays), street,

votive, etc .; they were accompanied by a procession of the cross,

blessing of water with the blessing of houses, livestock, fields, water

sources, etc., many days of festivities, feasts, fairs, sometimes

all-day bell ringing, etc.

Russian folk art goes back to the art of Ancient Russia, which

absorbed the artist. traditions of the ancient Slavs, Turks, Finno-Ugric

peoples, Scandinavians, Byzantium, Romanesque art of Western Europe, the

East. In pre-Petrine Russia, the artist. tradition, like all folk

culture, was the same for all social strata, and only from the

beginning. 18th century she became the property of arr. peasant art.

Among the widely developed types of Russian folk art are patterned

weaving and embroidery. They were an exclusively female occupation, the

art of a weaver and an embroiderer was considered one of the signs of a

good housewife. In the northern Russian regions, the textile ornament is

located in the main. in the form of a border, leaving the core. the

field of the product (towels, tablecloths, shirts, etc.) is smooth. The

red pattern prevails on a white or gray field, sometimes white on white.

Geometric ornament (primarily diamond-shaped mesh) with the inclusion of

plant (various types of wood), zoomorphic (roosters, peacocks,

two-headed birds, horses, lions, deer, etc.) and anthropomorphic

(frontal female figure, rider, etc.) motifs . In the central regions,

polychrome embroidery (red with green, blue, yellow, black) geometric

ornaments is common. In the southern regions of the main. type of

textile ornament - colorful details of women's clothing - ponevs, tops,

aprons, magpies. In the 15th century in Russia, facial sewing appeared -

the production of church covers, shrouds, shrouds, etc. with an icon

image. In ornamental embroidery, sewing on expensive fabrics with gold

and silver threads (drawn gold) or silk threads intertwined with the

finest gilded wire (spun gold) develops. From the 18th century father

begins. the production of metal thread and gold embroidery penetrates

into peasant life, especially in the North. In places, eg. in Torzhok,

it turned into a craft, on the basis of which in the 1930s. a gold

embroidery artel was created. In the 19th century under the influence of

the urban tradition of embroidery, handicraft is developing in the

villages of Mstera, Palekh, Kholuy, Vladimir Province. with

characteristic white embroidery on a thin white linen or cambric.

Embroidery craft existed in Novgorod (krestetskaya line: a relief

pattern of tightly intertwined threads over a large pulled out grid),

Nizhny Novgorod (guipure), Ryazan, Kaluga provinces, etc. An embroidery

factory in the city of Tarusa (Kaluga region) operates on the basis of

traditional craft. the production of patterned fabrics is maintained in

the city of Cherepovets (Vologda region).

A special type of Russian textile art is lace weaving, which has been

known among Russians since the 17th century. From the 18th century

monastery and patrimonial workshops play an important role in its

development. For Russian lace 17 - beg. 18th century geometric ornaments

are characteristic: rhombuses, triangles, zigzag stripes, then the lace

pattern becomes more complicated. Lace-making is preserved in the

Vologda, Lipetsk (especially in the Yelets region), Kirov (Sovetsk,

former settlement of Kukarka, Vyatka province), Ryazan (colored lace in

the city of Mikhailov; loin lace in the Kadom region) regions.

Carpet weaving was less developed. Lint-free carpets (carpets) were

woven on a horizontal mill, pile carpets (“mohr carpets”) were woven on

a vertical mill. The craft for the production of pile carpets

("Siberian") with geometrized floral ornaments arose in Tyumen (17th

century); lint-free carpets decorated with bright floral ornaments,

usually on a black field (close to a tray painting), - in the Kursk

province. (18th century); pile and lint-free carpets made of undyed wool

- in the Kurgan region. (19th century); in the beginning. 20th century

carpet weaving is developing in the village. Straw of the Penza

province.

The production of colored printed fabrics has been

known since the 18th century. in the Moscow province., and then in many

central and northern Russian regions. In the 19th century the art of

painting on fabric appears.

Artistic casting and forging of metal

have been developed in Russia since the early Middle Ages. Great Ustyug

(17th century), Nizhny Tagil (18-19th centuries), p. Lyskovo, Nizhny

Novgorod province. (19th century); in with. Pavlovo, Nizhny Novgorod

Province. in the 18th and 19th centuries the craft for the production of

copper figured locks was developed.

Russian jewelry art has

reached the highest development. In pre-Mongolian Russia, the most

complex jewelry techniques were developed: cloisonne enamel, niello,

granulation and filigree. Destroyed by the Mongol invasion, this art

resumed in the 14th-15th centuries. In the 18th-19th centuries. local

jewelry crafts arose: blackening on silver in Veliky Ustyug, revived in

the 1920s. thanks to the organization of the artel; enamel painting on

metal (finift) in Rostov, which was originally used to decorate church

utensils, icon frames, images, and then also toilet boxes, snuff boxes,

after being organized in the 1920s. artels "Rostov enamel" - women's

jewelry, caskets, etc. From the 16th century. the production of gilded

silver chased dishes, salaries, etc. is known in the villages of Krasnoe

and Sidorovskoye of the Kostroma provinces. Since the 19th century here

they began to make cheap jewelry made of copper with semi-precious

stones and glass, from the 1920s. - table services, goblets, etc. In the

16-17 centuries. there was a Bronnitsky craft - the manufacture of chain

mail and other armor (in the village of Sinkovo in the Moscow region,

now the Ramensky district), on the basis of which in the owls. time,

first the artel "Sinkovsky Jeweler" arose, and then the jewelry factory.

Artistic production. ceramics in Russia also dates back to the

pre-Mongolian period. In the 16th and 17th centuries in Moscow, elegant

black-polished dishes were made, imitating metal, simpler red-polished

and thin-walled white-clay with a stamped ornament. In the Yaroslavl

province. the production of black polished dishes persisted until the

20th century.

From the 10th–11th centuries in Russia, the

production of ceramic tiles with relief ornaments was known for

decorating ceremonial buildings, churches, etc. This art was revived in

the con. 15th c. In the 16th century stove tiles spread in Russia.

Initially, the tiles had a natural terracotta color, from the 16th

century. they were painted green and covered with glaze (“anted tiles”),

in the 2nd floor. 17th century tiles covered with polychrome enamel

spread. In the 18th century “Dutch” tiles imitating Western ones

appeared with blue or polychrome painting on a white background.

This style was transferred to the artist. crockery, figured ceramics,

etc., ch. arr. in the ancient (from the 17th century) ceramic center in

the village of Gzhel, Moscow Province. Gzhel craft was revived in the

middle. 20th century The second famous center of ceramic craft was in

the city of Skopin, Ryazan Province. Skopin tableware is characterized

by a relief ornament covered with colored glaze. In Gzhel, Skopin, in

the Vyatka settlement Dymkovo, in the Penza, Tula, Arkhangelsk

provinces, etc., clay figured painted toys, whistles, etc. were made.

Wood carving is one of the most traditional types of Russian art.

The few wooden products of the pre-Mongolian period that have come down

to us (mainly from Novgorod excavations) testify to the highest

development of wooden carving. The most famous is a column from

Novgorod, covered with a complex wicker and zoomorphic ornament. The

ancient tradition of wooden carving was preserved in peasant art in the

decoration of huts, utensils (dishes, spinning wheels, rollers, baby

cradles, sledges, etc.).

In addition to carving, wood painting

was widely used, and many local styles were formed here. For example, in

Pomorie, the Shenkur style of painting (flowers on a red background),

the Mezen style (drawing with black soot, made with a pen on a red-brown

background: images of running horses and deer), Severodvinsk, formed

under the influence of icon painting and book miniatures (drawing on a

light green, yellow and red background: girlish gatherings, horseback

riding, etc.; the center of the composition was often occupied by the

image of the Sirin bird, the background was filled with a grass

pattern). In the city of Gorodets, Nizhny Novgorod province.

multi-colored and inlaid with bog oak drawings (images of horses,

roosters, fantastic birds and animals, a floral pattern) were located on

a light background; in 1938, on the basis of this industry, an artel was

created, which in 1960 was transformed into the Gorodetskaya painting

factory. In con. 17 - beginning. 18th century a craft arose for the

production of turning wooden utensils painted with a lush herbal pattern

on a golden background in the village. Khokhloma of the Nizhny Novgorod

province. Wooden painted toys were produced in the village.

Bogorodskoye, Vladimir Province. (now the Moscow region) and Sergiev

Posad. Ancient centers of wooden carving existed in the villages near

Moscow. Akhtyrka and der. Kudrino; in the 19th century a workshop was

created in the nearby estate of Abramtsevo.

A special kind of

artist woodworking - carving on a birch burl. In the form of a fishery,

it existed in the 19th century. in with. Slobodskoye, Vyatka Province,

where boxes, cigarette cases, smoking pipes, and other items were made,

polished and varnished.

The traditional type of production for

Russians is the processing of birch bark. Birch bark tuesas were also

decorated with painting, embossing and embossing. In Veliky Ustyug and

nearby villages along the river. Shemogda, Vologda Province. a craft for

the production of birch bark products, covered with cut-out ornaments

(Shemogod birch bark), developed. The production of birch bark products

is preserved today in the Vologda and Arkhangelsk regions.

Artistic bone carving was especially developed in the Russian North. The

bone carving industry is famous in the village. Kholmogory Arkhangelsk

region (cut carving on walrus and mammoth ivory: caskets, vessels, snuff

boxes, combs, etc.). From the beginning 18th century bone-carving art is

developing in Tobolsk, where small sculptural groups are carved in the

local Siberian traditions: hunters, dog and reindeer teams, etc. In the

1930s. a center for bone and horn carving arose in the city of Khotkovo,

Moscow Region.

Stone-cutting art was highly developed in

pre-Mongol Rus. Numerous stone icons-images, in 12 - beg. 13th centuries

the art of facade carving flourished (white-stone cathedrals of

Vladimir-Suzdal Russia), revived in the white-stone architecture of

Moscow Russia of the 15th century. In contrast to the lush zoomorphic,

floral, woven and anthropomorphic pre-Mongolian ornamentation, Moscow's

white-stone cathedrals were decorated only with strict arched and

ornamental belts. Subsequently, with the development of brick

construction, ornamental architraves and other details were carved from

white stone. In the 18th and 19th centuries under the influence of

professional art, stone-cutting art (sculpture, writing instruments,

lamps, etc.) arises in the factories of the Urals (Kungur) and Altai

(Kolyvan village), in the Arkhangelsk region, Krasnodar Territory

(Otradnaya station); in the 20th century in with. Bornukovo, Nizhny

Novgorod province. the production of carved sculpture, vases, lamps, and

other items made of soft gypsum rocks appeared.

In the 18th

century the art of lacquer miniature, new to Russia, arose. In with.

Fedoskino near Moscow, this technique was used to make paintings,

ornamented boxes, boxes, etc. from papier-mâché. With the growing

popularity of the Fedoskino miniature among peasants and philistines,

scenes of festivities, tea parties, triplets, etc. began to prevail in

the painting. Fedoskino painting is also characterized by imitation of

Scottish fabric, tortoiseshell. Lacquer painting on papier-mâché also

developed in the ancient icon-painting centers of Palekh and Kholui in

Ivanovo and Mstera-Vladimir provinces. For Palekh painting, a black

background is characteristic, for Mstyora - light: blue, pink, fawn.

In the 18th century in Nizhny Tagil (in the Urals) there is another

new craft - lacquer painting on metal. At first, metal parts of

furniture, sleighs, etc. were decorated in this way, then the production

of painted tin trays was formed. Initially intended for a narrow circle

of factory owners, this art soon began to spread among the peasants

assigned to the factories, and then to distant markets. The famous

center for the manufacture of painted trays from the beginning. 19th

century became with. Zhostovo near Moscow. Located next to Fedoskino, at

first it was close to him in terms of artistry. traditions. Zhostovo

trays were also originally made from papier-mâché. The murals of the

Nizhny Tagil and Zhostovo trays at first reproduced easel painting

(still lifes, landscapes, genre scenes, in Nizhny Tagil - scenes on

antique subjects, in Zhostovo - tea parties, troikas, etc.), then lush

floral ornaments became predominant.

For Russian folklore, see

the Literature and Musical Culture sections.

The indigenous peoples of the European North and North-West of Russia belong to the Finno-Ugric (Saami, Karelians, Vepsians, Vods, Izhoras, Ingrian Finns, Seto Estonians, Komi and Komi-Permyaks) and Samoyedic (Nenets) groups. Among the majority of the indigenous peoples of the European North, the White Sea-Baltic version of the Baltic race predominates; in the east, features of the Ural race are traced (especially among the Nenets). The Saami are dominated by the Laponoid variant of the Ural race.

The peoples living in the tundra and forest-tundra (Saami, northern

groups of Karelians, northern Komi-Izhma, Nenets) were engaged in

reindeer herding, fishing and hunting (including driven hunting for

deer), the Saami were engaged in hunting. Among the Nenets and

Komi-Izhemtsy, reindeer breeding was widespread. Samoyed type, based on

distant (sometimes more than 1 thousand km) seasonal migrations (in

summer they migrated to the ocean coast to the north, where herds

suffered less from midges, in winter - to the south, to the

forest-tundra region). The herds consisted of several thousand heads,

grazing with the help of a shepherd's dog. Traditional Saami reindeer

husbandry was also based on seasonal migrations: in winter, reindeer

grazed in the interior forest regions of the Kola Peninsula, in spring

and summer they migrated to the coast; deer grazed in winter under the

supervision of a shepherd and a dog, and in summer they were transferred

to free grazing, while their owners were engaged in fishing and hunting.

Reindeer breeding was borrowed from the Saami and sowing. Karelians (in

the Kemsky district). Reindeer gave meat and skins, as well as (for some

groups of the Sami) milk, were used in a team: among the Nenets and

Komi-Izhma people they were harnessed to sloping dust sledges of the

Samoyed type, among the Sami - into a kind of single-track sleigh,

shaped like a boat (kerezha); the Sami knew the use of deer under the

pack. Modern The Saami completely switched to the Samoyed type of

reindeer husbandry. Main food - raw, boiled, frozen and dried (yukola)

meat and fish, raw, frozen and soaked berries. The traditional dwelling

of the peoples of the tundra is the tent, among the Sami - a hut

(kuvaksa) similar to the tent. In the past, the Saami had a

truncated-pyramidal frame structure, covered with turf, with a hearth

and a smoke hole in the center - a vezha (kuet). Later, log dwellings

with a flat, slightly sloping roof (pyrt, tupa) and Russian huts

appeared. The clothes of the reindeer herders of the tundra had a blind

cut and were sewn from reindeer skins with fur inside (Nenets malitsa)

or outside (Sami stove), decorated with fur mosaics; the Saami also

developed applique on cloth, leather, beadwork, knitting with a needle,

weaving belts on reeds.

The peoples living in the forest zone

(Karelians, Vepsians, Vods, Izhoras, Setos, Finns-Ingrian, Komi-Permyaks

and B. h. Komi) were engaged in the main. northern (slash-and-slash)

agriculture (sown rye, barley, oats), forest animal husbandry and

gardening, fur and upland hunting, river and sea (Izhora, Vod, Ingrian

Finns) fishing, lived in villages in log cabins of the North Russian and

Central Russian type; stone was often used in the foundation and

outbuildings (Ingrian Finns, Izhora, Vod, Seto). Residential and

outbuildings were connected according to the type of L- and T-shaped

connection. The archaic design was preserved by hunting huts on poles

(among the Komi), shepherd's conical huts, sheds for youth games

(kizyapirtya) among the Karelians. Traditional clothing is close to

northern Russian: a shirt and trousers for men, a shirt and a sundress

for women; the Vepsians and Ingrian Finns also had a skirt complex.

Archaic elements of women's clothing were preserved: an unsewn skirt

(khurstuket) with sewn-on cowrie shells and a leather belt decorated

with metal plaques (indicating connections with the Volga Finno-Ugric

peoples), an embroidered towel headdress among Izhorians, Vodi and Setu,

shirts with chest embroidery wool among the Ingrian Finns; Until now,

there is a unique set of silver breast jewelry for women seto. The main

outerwear of men and women is a cloth caftan. A kind of male and female

headdress among Karelians is a fur three-piece. Patterned knitting was

developed (including the archaic method of knitting socks and mittens

with one needle among the Vepsians, Komi and Karelians) and weaving,

embroidery, weaving belts, carving and painting on wood (dishes, chests,

spinning wheels), birch bark processing. In each region there were local

artists. traditions. The food of the forest peoples of the North is

close in composition to the food of the sowing. Russian groups.

The folklore of the peoples of the European North is represented by

fairy tales, historical legends, myths, everyday stories,

improvisational songs, ritual songs, epos (the code of

Karelian-Finno-Izhorian runes "Kalevala", recorded and revised by E.

Lönrot, 1849).

The most ancient folklore genres of the Baltic

Finns include Karelian yoik improvisations and wailing and lamentations,

which are still common among Karelians, Izhors and Vepsians. The core of

the genre system of the majority of the Baltic-Finnish peoples is made

up of monophonic runic songs with the so-called. Kalevala verse (epic,

wedding, lyrical); the most archaic are the Vod runes. In the past,

Karelian runes were performed by two rune-singers in turn, perhaps

accompanied by a kantele, later they were sung alone; vodskie were

performed by the lead singer and the choir. A living runic tradition has

been preserved in North Karelia (villages of the Kalevalsky district),

outstanding rune singers are members of the Perttunen family (19th–20th

centuries). The late layer of folklore includes lyrical, round dance,

dance songs with rhymed verse, ditties. A special genre of song and

dance folklore of the Ingrian Finns is röntushki; was formed during the

merger of the features of Russian quadrilles, ditties, Finnish wedding

songs and round dances. Vepsians are characterized by a variety of

muses. tools. Setu is typically characterized by heterophonic polyphony,

close to the Russian and, presumably, Mordovian tradition.

The

main genres of Sámi folklore are lyrical and comic-satirical

songs-improvisations (yoigi), personal songs, legend songs, lullabies.

Special songs are sung by reindeer herders, hunters, and fishermen.

The most stable part of the folklore of the Komi and Komi-Permyak

peoples includes lamentations and songs (mostly polyphonic) - family

ritual (wedding, recruiting), calendar (Zyryansk and Permian Christmas

circular and game, Trinity; Zyryansk Shrovetide, reaping, Permian

swing), as well as untimed lyric, dance. The archaic layer is

represented by rare examples of spells (Zyryansky "Expulsion of

thistle-tatar man from the field", "Expulsion of Klop Klopovich from the

hut"), cattle-breeding conspiracies (addressed mainly to cows),

household improvisations. Epic genres are locally widespread: Izhma and

Pechora lyric-epic improvisations of nurankyy, Izhmo-Kolvin heroic

legends (“Kuim Wai-Vok”), Vym and Upper Vychegoda epic songs and ballads

(“Kiryan-Varian”, “Pyodor Kiron”). Among the local traditions of the

Komi, the Izhmo-Kolvinskaya tradition, which was influenced by Nenets

folklore, has the greatest originality; among other Komi groups, Russian

influence is noticeable. The similarity between the Zyryansk and Permyak

folklore is most evident in instrumental music. Until recently, stringed

bowed and plucked sigudok, women's multi-barreled flutes (Zyryan kuima

chipsan, Permian polynes) and others were common; from the beginning

20th century there is a harmonica.

The folklore of the Nenets of

the European North is close to the folklore of the Nenets of Western

Siberia.

Orthodoxy spread among the Karelians, Vodi, Izhora and Vepsians from

the 13th century. From 1379 Stefan of Perm, the first bishop of the Perm

diocese, was engaged in educational activities among the Komi (Perm);

the writing system he created existed until the 17th–18th centuries.

There were many followers of the Old Believers among the Karelians and

Komi. The Christianization of the Saami was started by the monks

Theodoret of Kola and Tryphon of Pechenga in the 16th century. In order

to convert the Nenets to Christianity in 1824, a "Spiritual Mission for

the conversion of the Samoyeds to the Christian faith" was created in

Arkhangelsk. The first translation of the Gospel into Karelian was made

in 1852, and into Sami in 1878. The Ingrian Finns belong to the

Evangelical Lutheran Church of Ingria and use the Latin script (see

Protestantism in Religion).

All the peoples of the North and

North-West retained the veneration of the owners of the forest, water,

sacred trees, and the Saami - stones.

A new script for the Komi

and Komi-Permyaks, using Russian and Latin graphics, was created in 1920

by V. A. Molodtsov; in 1932, they, like the Nenets, introduced the Latin

script, then Russian. In the 1930s an attempt was made to introduce

writing among the Karelians, Vepsians and Kola Saami; The written

language of these peoples was recreated in the 1980s. (among the Saami -

based on Russian, among the Karelians and Vepsians - on the basis of

Latin graphics).

The indigenous peoples of the Volga and Ural regions are the peoples

of the Finno-Ugric (Mordovians, Mari, Udmurts, Besermens) and Turkic

(Chuvash, Tatars, Kryashens, Nagaybaks, Bashkirs) groups; later,

Russians and Kalmyks speaking one of the Mongolian languages appeared

here.

Among the indigenous peoples of the Volga and Ural regions,

representatives of the Central European race predominate; South

Caucasian admixtures (Balkan-Caucasian and Indo-Mediterranean races) are

traced in the south. Among the Bashkirs, signs of the South Siberian

race are strong, Kalmyks in the main. belong to the Central Asian

variant of the North Asian race.

The ancestors of the Finno-Ugric

tribes are presumably associated with the carriers of the Neolithic

cultures of the 3rd - early. 2nd millennium BC e. At this time, they

have the beginnings of agriculture, in the last quarter. 2nd millennium

BC arable agriculture takes shape, disappearing in the 1st millennium

BC. e. and re-emerging after 500 AD. An important role was played by the

contacts of the population of the Volga region with more southern and

eastern (Iranian, Turkic and Ugric) peoples. From the 1st millennium AD

Turkic-speaking groups penetrate into the Volga region from the south.

Of the early Turkic migrations, the migrations of the Bulgars and Suvars

(late 7th - early 8th centuries), Pechenegs and Oguzes (9th-10th

centuries), and Kipchaks (12th century) are of the greatest importance.

The beginning of the late Turkic migrations is associated with the

processes of weakening and disintegration of the Golden Horde, among

them the resettlement of the Kipchaks in the con. 14 - beginning. 15th

centuries, which influenced the formation of the Tatars and Bashkirs.

Russians are widely settled in the Volga region after the fall of the

Kazan Khanate (1552). The ancestors of the Kalmyks, the Oirats (western

Mongols), appeared in the Lower Volga region in the middle of the 17th

century.

In the Volga region, 3 economic and cultural zones are formed: 1) the

forest north (most of the Finno-Ugric peoples), where forest activities

retained an important role in agriculture and animal husbandry -

hunting, fishing, beekeeping, apiary beekeeping, logging, charcoal

burning, tar smoking, tar race and turpentine; 3) The steppe and

forest-steppe southeast (Bashkirs and Kalmyks), where nomadic or

semi-nomadic cattle breeding dominated (sheep, horses, cattle, goats,

and among Kalmyks also camels), combined in places with agriculture

(near winter camps). Later, under the influence of the Russians, arable

farming finally became the dominant occupation, and features similar to

East Slavic culture spread. The Kalmyks switched to settled life only in

the 1930s.

The three-field farming system was combined in some

places with more archaic systems: with slash-and-burn in the forest zone

and shifting in the steppes and forest-steppes. The main arable

implements were a plow, a Vyatka-type roe deer, a plow, a wheeled

plow-saban. Of grain crops, rye, barley, oats prevailed, less often

millet, spelt, and of industrial crops - flax and hemp.

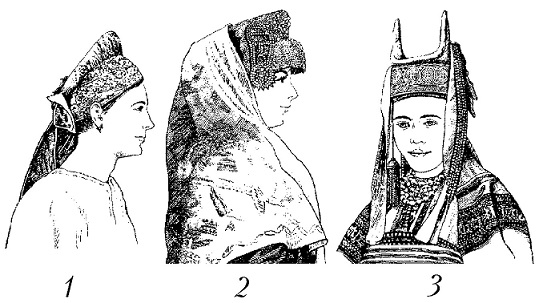

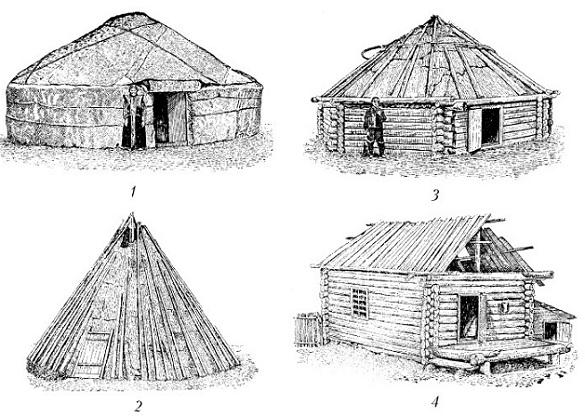

The interior of the Bashkir yurt.

Rural settlements usually consisted of several dozen households in

the forest zone, and several hundred in the forest-steppe and steppe. In

the forest and forest-steppe regions of the main. the type of dwelling

was a hut on the basement, in the north - often on a stone foundation,

with a Russian stove and a layout of the northern Central Russian, in

some places - Western Russian type. In treeless areas, adobe, adobe,

wattle (smeared with clay), sod, and stone houses were common. Among the

nomadic Bashkirs and Kalmyks, a felt yurt was a traditional portable

dwelling; Bashkirs, who were engaged in semi-nomadic cattle breeding,

lived in log houses on the site of winter quarters. All peoples, except

the Kalmyks, had light log buildings with an open hearth, serving as a

temporary or summer dwelling, a summer kitchen, a place of worship, etc.

).

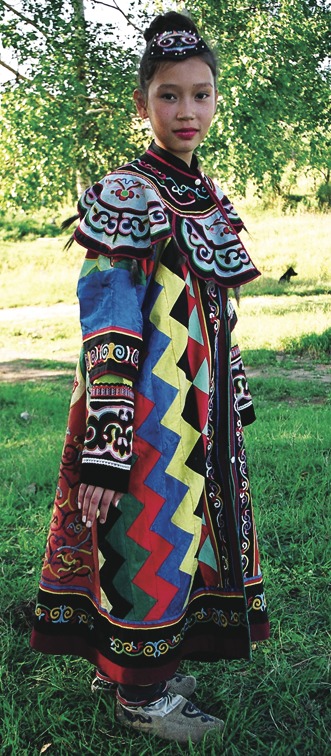

The main elements of clothing were a tunic shirt and trousers.

Over the shirt they wore loose clothes made of fabric or cloth with a

straight-back cut (Tat. and Bashk. Bishmet, Tat. Chikmen, Zhilen, Bashk.

Sekmen, Yelen, Udm. Shortderem, Mar. Shovyr) or flared from the waist

(Tat. Kezeki, Chuvash. shupar, sahman, udm. sukman, dukes, mar. myzher,

shovyr), in winter - fur coats. Under outerwear or at home, they wore

short, loose-fitting clothes without sleeves or with short sleeves like

a camisole. Women sometimes wore an apron, a dress, a large amount of

jewelry made of copper, bronze, silver, gold and other metals, precious

and semi-precious stones over their shirts: necklaces, clasps-sulgams

(Mordva), plaques, bibs with coins, plaques, cowrie shells, beads, etc.,

back decorations, shoulder straps, etc.

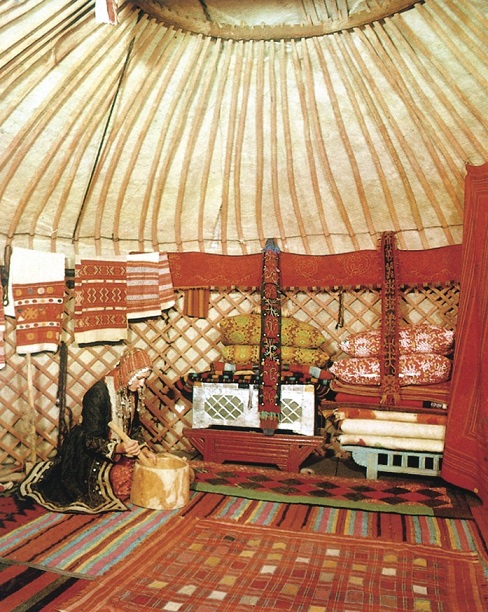

Nizhny Novgorod Tatars. 19th century

Men's hats - felt hats, Tatars and Bashkirs - skullcaps, in winter -

fur (lamb, etc.) hats. Among women's hats, 4 types can be distinguished:

a) a high cone-shaped hat on a solid base (udm. aishon, mar. shurka,

muzzle. pango); b) a small cone-shaped hat (Udm. Podurga, East-Mar.

Chachkap, Chuvash. Khushpu, Tat. Kashpau, Bashk. Kashmau; girlish - Udm.

Takya, East-Mar. Takiya, Moksha-Mord. Takya, Chuvash. tukhya, tat and

bashk takyya); c) towel dress (Udm. turban, Mar. Sharpan, Chuvash.

Surpan, Tat. and Bashk. Tastar); d) headband with side ties. Headdresses

were decorated with embroidery, braid, sequins, corals. Other forms of

headwear were also common: spade-shaped (magpie) among the Mari and

Mordovians, a kalfak hat among the Tatars and Bashkirs, and others.

shoes - bast shoes, felt boots, boots, among Kalmyks in winter - with

felt stockings; the Tatars wore boots made of thin leather (ichigi), the

Bashkirs wore high boots with a leather bottom and a felt shaft (kata).

Bread, pies, cakes, pancakes, cereals, stews were made from flour

and cereals, beer, kvass, and mash were made from drinks. Meat was

important to pastoralists; Horse meat was used by the Tatars, Bashkirs,

Kalmyks, Mari, as sacrificial food - also by the Udmurts and Chuvashs.

Pork was not eaten by Muslims, as well as those Mari and Udmurts who

adhered to traditional beliefs. Dairy drinks are characteristic: from

cottage cheese or sour milk diluted with water, koumiss (especially

among the Bashkirs), milk kvass and milk vodka (among the Kalmyks).

Kalmyks prepared a drink from tea with the addition of milk, butter,

salt, spices (Kalmyk tea, or jomba).

Bashkirs

In the late 19th century in the Volga and Ural regions, the rural population prevailed, the urban strata occupied a prominent place only in the composition of the Tatars. A small family prevailed, a large (undivided) family was preserved for a long time among the Mordovians, and partly among the Udmurts. There were associations of related families (especially among the Udmurts, Maris, Bashkirs, part of the Tatars), as well as tribal groups associated with joint participation in rituals (among the Udmurts, Maris, Mordovians). Some of the Tatars and Bashkirs had territorial districts (Tat. Zhien, Bashk. Yiyyn), uniting several. villages, whose inhabitants once a year gathered for holidays. Some of the Bashkirs retained tribal groups that received from the state patrimonial rights to the lands they occupied. Among the Kalmyks, both paternal and maternal family associations played an important role; in adm. In respect they were divided into uluses, aimags and khotons.

There are links in art with the art of the peoples of Siberia,

Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the European North. Among the Udmurts,

Mordovians, Chuvashs, a geometric ornament is more common, among the

Tatars - a floral ornament. All the peoples of the Volga and Ural

regions developed embroidery, patterned weaving, and woodcarving.

Patterned knitting was most developed among the Udmurts and Bashkirs,

embossing on birch bark - among the Udmurts and Maris, weaving from a

vine - among the Udmurts, Maris, Chuvashs, beadwork - among the

Mordovians, mosaic on the skin - among the Tatars, embossing on the skin

- among the Bashkirs, Kalmyks (Kalmyks know leather vessels

characteristic of nomadic life), carpet making - among the Bashkirs,

patterned felt making - among the Tatars and Bashkirs, jewelry art

(weapons, hunting equipment, harness parts, jewelry, smoking pipes,

etc.; from jewelry techniques engraving, chasing, filigree, granulation,

inlay, blackening, cutting and polishing of precious stones are known) -

among the Tatars, Bashkirs, Kalmyks, stone carving - among the Tatars.

Traditional art forms are now preserved in the form of handicrafts.

traditional beliefs. Some of the Udmurts, Maris, and Chuvashs have

long preserved, and in some places still exist, pagan cults: prayers and

sacrifices in sacred groves, led by special priests (Udm. Vosyas, Utis,

Mar. Kart, Vost.-Mar. Molla, Chuvash. yumzya), etc. A special place

among the peoples of the Volga region is occupied by holidays dedicated

to the end of field work (Tatar and Bashk. Sabantuy, Bashk. Habantuy,

Chuvash. Akatuy, Mar. Agavairem, Udm. Gyron Bydton, Mord. ozks).

Oral tradition retains a connection with calendar and family rituals:

timed genres form the core of the vocal tradition of the Udmurts (songs

of prayers, wires of melt water, wires of flax, Akashka plow festival,

Portmascon festival of mummers), Chuvash, Mari, Mordovians (pazmorot

songs performed during time of prayers ozks), Kryashens. Guest and

drinking songs are widespread among the Chuvash, Mari, Udmurts and

Kryashens. Chuvash labor songs are diverse (songs of felters, songs when

weaving matting). The Udmurts have preserved songs-improvisations for

the occasion (hunting, beekeeping, bee spells, personal songs). Untimed

genres form the basis of the genre system of Bashkir and Tatar folklore:

lingering songs (ozone-kuy among the Bashkirs, ozyn-kuy among the

Tatars), “short songs” (kyska-kuy), ditties (takmak). Among the Bashkirs

and Muslim Tatars, the epic genre of bait, the religious and didactic

munajat, the chanting reading of the Koran, and everyday prayer singing

are widespread. Epic forms are also represented by recitative Bashkir

kubairs and Mordovian narrative songs of kuvaka morot. For Kalmyk

folklore, as well as for Turkic and Mongolian cultures in general, the

opposition of “long songs” (utu dun: many lyrical, wedding, songs of the

calendar holidays Zul and Tsagaan Sar, pastoral songs-spells) and “short

songs” (ahr dun : comic, dance). The central genre of the oral culture

of the Kalmyks is the heroic epic "Dzhangar", performed by professional

singers-narrators of dzhangarchi, among whom the most famous is Eelyan

Ovla.

The traditional form of singing of Tatars, Bashkirs is

monodia; among the Mari, Chuvash, Udmurts and Kryashens, heterophony

prevails, the folk music of the Mordovians is distinguished by the most

developed polyphony. A specific type of traditional singing, known among

the Bashkirs, is the solo two-voice uzlyau (similar to the throat

singing of the Altaians and Tuvans). In the songs of the Kazan Tatars,

Mari, Chuvash, the pentatonic scale dominates.

Instruments: longitudinal kurai flute among the Bashkirs and Tatars; a gusli-type instrument - krez among the Udmurts, ksle among the Chuvash, kyusle among the Tatars; bowed srme kupas among the Chuvash, iya kovyzh among the Mari, garze (gaiga) among the Mordovians; plucked dombra among the Kalmyks and dumbyra among the Bashkirs; bagpipes - shuvyr among the Mari, shapar and srnay among the Chuvash, archaic bagpipes-bubble fam among Moksha, puvama among Erzi; paired wind reed nude among the Mordovians; natural pipes - Udmurt hunting chipchirgan, Mari ritual puch, Mordovian shepherd's torama; kubyz jew's harp among the Bashkirs and Tatars; various percussion, rattles. From con. 19th century there is a harmonica brought by the Russians.

Among the Udmurts, Mordovians, Maris and Chuvashs, the majority of believers are Orthodox, among the Tatars and Bashkirs - Sunni Muslims, Kalmyks - Buddhists (see Islam and Buddhism in the article Religions). Islam began to spread among the peoples of the Volga region (in the Volga-Kama Bulgaria) in the 10th century. The Christianization of the peoples of the Volga region began in the 15th century. and intensified after the fall of the Kazan Khanate in 1552. The first Mari alphabet, developed by Archbishop Gury of Kazan in the middle. 16th century, was forgotten. Writing based on Russian graphics in the languages of the Finno-Ugric peoples and Chuvash originated in the 18th century. From Ser. 19th century in Kazan there was a missionary society "The Brotherhood of St. Guria”, formed by N.I. Ilminsky, a broad translation activity was undertaken, a network of schools with teaching in native languages was created. The Tatars and Bashkirs had a written language based on Arabic script, which was translated into Latin in 1927–28, and into Russian script in 1939–40. The Kalmyks had a written language created in 1648 by the preacher of Buddhism, Zaya Pandita, based on the Mongolian alphabet; in 1924, the Russian alphabet was introduced (in 1930–38, the Latin alphabet).

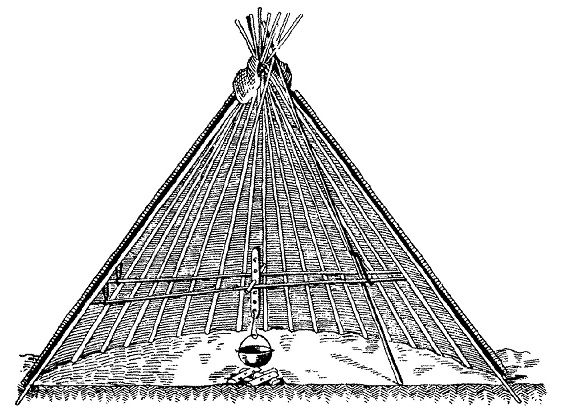

Chum (Komi - Chom) Portable dwelling of the peoples of the North and Siberia. It had a conical frame of long poles with tires: in winter - from deer skins or rovduga (nyuki)

The indigenous peoples of Western Siberia speak the languages of the

Uralic (the Finno-Ugric group includes the Ob Ugrians - Khanty and

Mansi, the Samoyedic - Nenets, Enets, Nganasans and Selkups) and Yenisei

(Kets and Yugi) families; Siberian Tatars and Chulyms belong to the

Turkic group of the Altai family.

The peoples of the Ural family

were formed by the beginning. 2nd millennium AD e. as a result of the

resettlement from the south in several waves (starting from the

beginning of the 2nd millennium BC) of pastoral peoples - the ancestors

of the Ugrians and Samoyeds - and their mixing with local tribes of

hunters, fishermen and gatherers. Also, speakers of the Yenisei and

(from the 6th–7th centuries to the early 20th century) Turkic languages

settled from the steppe south.

Anthropologically, the Khanty,

Mansi, Nenets, Selkups, Kets in the main. belong to the Ural race, the

degree of Mongoloidity increases towards the northeast. Among the Enets

and Nganasans, the Baikal (Katangese) variant of the North Asian race

predominates. The Tatars combine features of the South Siberian and Ural

nations.

Mansi woman in a Sakha fur coat.

The peoples living in the tundra and forest-tundra (tundra Nenets and

Enets, Nganasans, northern groups of the Selkups, Khanty and Mansi)

practiced reindeer husbandry of the Samoyed type. Reindeer breeding was

especially developed among the Nenets; supplemented by hunting,

including wild deer, gathering (berries, etc.) and fishing. The

settlement of tundra reindeer herders is a camp of a group of kindred

families, the traditional dwelling is a chum. The traditional clothes of

reindeer herders were ideally adapted to the conditions of life in the

tundra with distant migrations on sleds. Clothes and shoes were made

from deerskins (often trimmed with dog fur) and worn in two layers: fur

on the inside and outside. Men's clothing - blind cut, below the knee

length, with a hood: fur inside (malitsa - Nenets. Maltsya, Khanty.

Malta, Mansiysk. Molsyan) and out (parka - Selkup. Pargy, Mansiysk.

Porkha, Nganasan. Lu; Goose - Khantysk Kus, Mansi Punk jug, Sovik -

Nenets sook, Selkup Sokky, Nganasan Fia); on the road, a parka or a

sovik could be worn over a malitsa. Among the Nenets, sowing. Khanty and

Mansi clothes are sewn from two whole pieces of skin (the so-called Ural

type), among Nganasans and Enets - from small pieces (the so-called

Taimyr type). Women's clothing (Nenet pans, Khanty sakh, sak, Mansi

sakhs) is a double long fur coat (the so-called West Siberian type),

among Nganasans and Enets it is shorter, worn with overalls. In the

summer they wore cloth clothes. Winter shoes - fur boots sewn with fur

outside (pimy, kisy - Nenets beer, Selkup pema, Khanty vai, vei, nir,

Mansi nyara), worn on fur stockings with fur inside. Among the Nganasans

and Enets, the shoes did not have an instep.

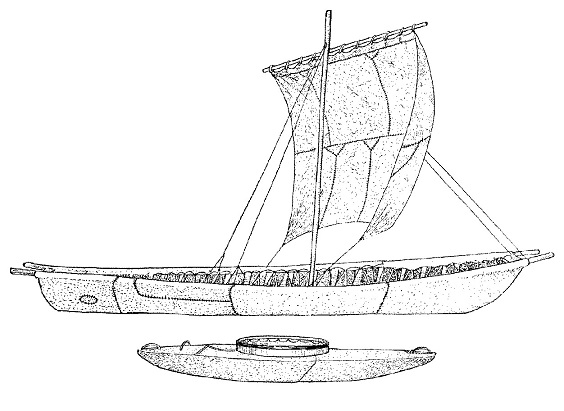

The peoples living

in the taiga zone (the Forest Nenets and Enets, mostly Selkups, Khanty,

and Mansi, the Kets, and part of the Siberian Tatars) were engaged in

hunting, fishing, and gathering on foot; there was reindeer breeding of

the taiga type. The fishing area extended for a distance of approx. 100

km around winter settlements. Winter dwellings - ground, dugouts and

semi-dugouts, log or frame, usually heated by hearths-chuvals. The

Forest Nenets and Enets lived in tents. During fishing and hunting

(spring, summer and autumn), they lived in temporary light buildings

with a frame of poles covered with birch bark or larch bark. In winter,

they traveled on reindeer and dog sleds, hunters in fishing - on skis,

in summer - on water in dugout and plank boats, on long trips - in boats

with a cabin. The upper clothing of the peoples of the taiga was, as a

rule, of swing cut. Winter clothes were sewn in the main. from the skins

of wild animals and birds (squirrel, arctic fox, marten, hare, duck) and

deer, summer robes and caftans - from cloth and purchased fabrics. Men

and women also wore shirts and trousers, women - dresses of a deaf cut

(Khantysk. Ernas, Mansiysk. soup). Main food of reindeer herders and

hunters - raw, frozen, boiled and dried meat (venison, game) and fish,

berries, nuts; mushrooms were not eaten (toadstools were used as a

hallucinogenic agent); Khanty and Mansi used horse meat as sacrificial

food.

Fur clothes were decorated with mosaic ornaments, ribbons, tassels

made of colored cloth, beads, fabric clothes - with appliqués. Women

wore earrings, beads, rings, khanty and mansi - pectoral ornaments woven

from multi-colored beads. Nganasan and Enets clothes (especially women's

overalls) were decorated with metal copper and tin plaques, plates,

tubes, bells, and bells. Ornament (the so-called Ob type) - silhouette,

geometric motifs: rectangles, rhombuses, inscribed triangles, meanders,

crosses; complex horn-shaped figures form borders and rosettes;

Khanty-Mansiysk names of traditional ornamental motifs are

characteristic - “hare ears”, “birch branches”, “sable footprint”,

“man”, etc. applications. Wood carving (spoons, scoops, hooks for

cradles, oar handles, backs of sleds) and mammoth tusk (smoking pipes,

spindle whorls, needle beds, belt buckles and reindeer harness buckles,

knife handles, sometimes with endings in the form of sculpted heads of

animals and birds). Sculptural images of patron spirits and ancestors

were carved from wood.

The inhabitants of villages located in the

floodplains of large rivers (Ob and Yenisei) and south. forest-steppe

regions of Western Siberia (part of the Khanty and Mansi, southern, or

Narym, Selkups, Siberian Tatars), DOS. fishing was a traditional

occupation, in addition, they were engaged in hunting and gathering,

agriculture was widespread (vegetables, from cereals - barley, wheat,

rye, oats, millet) and animal husbandry (especially among the Tatars).

In the culture of these peoples, the influence of Russians is strong,

among the Tatars - the peoples of Southern Siberia. In food, fish, meat

are common (the Tatars also have horse meat), milk, vegetables, and

bread. Dairy products are especially traditional among Tatars: cream

(kaymak), sour-milk drinks (katyk, ayran), butter, cottage cheese,

cheese. Along with dugouts, semi-dugouts, log dwellings, the Tatars also

have houses made of turf bricks, wattle plastered with clay, heated by a

chuval and a stove with a cauldron embedded in it; in the interior of

the dwelling - bunks covered with mats, skins, among the Tatars -

carpets, felt, chests. Wooden houses were sometimes decorated with

carved architraves, skates with a figurine of a bird or a horse. The

clothes of the Khanty, Mansi and Selkups experienced Russian influence.

Main type of Tatar clothing - caftans (beshmet) and robes (chapan) of a

tunic-like cut (the so-called West Siberian type) made of homespun or

imported Central Asian silk fabric, camisoles without sleeves or with

short sleeves, pants, shirts, for women - shirt dresses, morocco boots

(ichigi), in winter - fur coats (ton, tun); men wore skullcaps, felt and

fur hats, women wore headbands on a solid base, sheathed in fabric with

a braid and beads (tat. saraoch, sarauts), scarves, and numerous

jewelry.

Traditional cults - worship of master spirits, patron

spirits, ancestors, totemic cults (worship of animal ancestors,

including bear and elk), shamanism; calendar holidays: the winter Bear

holiday among the Khanty, Mansi and Kets, the spring women's Crow's day

among the Khanty and Mansi, the spring holiday of the Pure Plague among

the Nganasans (the holiday of the end of the polar night), etc.

In the folklore of the peoples of Western Siberia, mutual influences

and connections are traced both with each other (between the Kets and

Selkups; Khanty and Mansi; Nenets, Enets and Nganasans) and with the

peoples of other regions (Saami, Evenki, Dolgans, Yukagirs); south the

origin of the ancestors of the Samoyeds, Ugrians and Kets explains the

presence in their folklore of traces of Iranian and Turkic mythology.

Under Russian influence in mythology, biblical stories (the motif of the

Flood, making a man out of clay and blowing a soul into him, creating a

woman from a man's rib, etc.) and Christian characters (Christ, Nicholas

the Wonderworker) became widespread.

Cosmogonic, anthropogonic

and ethnogonic myths, other mythological stories (including cycles about

cultural trickster heroes who combine serious creative deeds and heroic

deeds with picaresque tricks), tribal and historical legends, epic

songs, hunting and shaman legends, parables, bylichki about meetings

with spirits, fairy tales about animals, everyday and fairy tales;

various forms of ritual folklore, as well as small genres - riddles,

prohibitions, signs, etc. Epic, ritual and lyrical genres are

distinguished.

The epic is presented in ch. arr. mythological,

heroic (for example, syudbabts among the Nenets, dastans among the

Siberian Tatars) or life-descriptive (for example, yarabts among the

Nenets, baits among the Siberian Tatars) legends. Typical plots are

about heroic matchmaking and getting a wife, revenge for killed

relatives, battles with cannibal giants, the struggle for deer herds,

about the wanderings and misadventures of a destitute hero, etc. The

most large-scale texts (performed for several hours, and sometimes

evenings) are known from the Nenets, from whom, apparently, they were

borrowed in a transformed form by the Enets and Nganasans. Among the

Khanty and Mansi, legends about the divine origin of the bear, about the

ancestors-heroes and their exploits, etc., could be accompanied by

playing the harp or zither and included in shamanic rituals and the bear

festival; in some groups of Khanty, storytellers were endowed with

magical abilities to heal the sick. Usually the epic is performed in

recitative, song or mixed song-recitative form; often the story is told

from the perspective of a hero or heroine; A specific feature of

Samoyedic folklore is the image of the narrator (the personification of

a “song” or “word”), who follows the course of events and comments on

them.

Ritual folklore includes wedding and funeral laments,

spells before hunting, etc. A special area of ritual folklore is

shamanic singing. The summoning of helper spirits by the shaman, appeals

to the spirits, their replies, descriptions of the shaman's travels to

other worlds, etc., were accompanied by beats of a tambourine and the

ringing of bone or metal pendants-rattles on the shaman's suit,

tambourine or staff. The melodies of shamanic songs were considered to

be the voices of the spirits on whose behalf the shaman performs (as

well as ventriloquism, onomatopoeia, emphatic intonation).

Among

the Siberian Tatars, the old ritual genres were supplanted by the

singing of prayers and surahs of the Koran.

Lyrical genres -

personal songs and song improvisations about the world around, love

relationships, successful hunting or life events, relatives, etc. (the

so-called songs of fate); lullabies among the Khanty, praise songs

(ulilap) among the Mansi, song greetings and good wishes, “drunken

songs”.

Solo singing predominates in all cultures. An assistant

can participate in the performance (shamanic singing, epic Nenets). The

lyrical songs of the Turkic peoples are sometimes performed by a unison

or heterophonic ensemble or accompanied by an instrument. Typical tunes

are widespread, on which new texts are improvised; there are songs in

which the text is assigned to the tune. Nganasans are known for song

dialogues - competitions in composing songs-allegories, unique in melody

and sophisticated in the mechanism of encryption. Characteristic are

narrow-volume (from a second to a sixth) and wide (about an octave or

more) scales. Step zones in width can exceed a whole tone. The relative

simplicity of the scales is compensated by a variety of intonation

contours of steps - with gliding in the initial and final phases, with

mordent-like movement, etc. Such contours and the pitch uncertainty

associated with them (with an easily detectable pentatonic basis of the

scale) are most clearly manifested in the music of the Siberian Tatars.

Rhythmic organization is characterized by a tendency to ostinato and

repetition of quantitative rhythm formulas, which can vary greatly, and

then the rhythm is perceived as outwardly non-periodic (for example, in

the epic and lyrical songs of the Selkups). As in other regions of

Siberia, specific articulatory-timbre expressiveness is of great

importance. The “sacred songs” of the Mansi Bear Festival are sung with

a special laryngeal (throat) timbre.

Main music. instruments:

bowed lutes, zithers (Mansiysk. sankvyltap), among the Selkups and Ob

Ugrians - harps (Khantysk. top-yukh - lit. "crane-tree", Mansiysk.

tarygsyp-yiv - "tree of the crane's neck"), shaman tambourines, jew's

harps, hunting decoys, sound toys (whistles, pipes, squeakers and flutes

made from a stalk of hollow grass or a bird's feather, buzzers), etc.

Borrowed harmonica and (except for the Siberian Tatars) balalaika are

ubiquitous. Most cultures have recorded solo tunes.

Dances were

performed mainly on calendar holidays. The circular dances of the

Nganasans and Enets during the spring festival of the Pure Plague were

accompanied by exclamatory tunes on inhalation and exhalation (the

so-called throat wheezing). At the Bear Festival, the Khanty and Mansi

performed dances to the accompaniment of a zither or harp, representing

certain tribal or territorial groups, as well as “spirit dances” - the

patron ancestors of these groups, theatrical skits and pantomimes of a

comic and at the same time magical content; some of these theatrical

performances included dress-up and elements of puppet theater.