Location: Kreva village Map

Constructed: 14th century

Kreva Castle (Крэўскі замак / Krevskiy zamok / Krėvos pilis), located in the village of Kreva (Krevo) in Smarhon District, Grodno Region, Belarus, is one of the oldest and most significant stone fortifications in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL). It was constructed in the early 14th century (with possible beginnings in the late 13th century) under Grand Duke Gediminas and/or his son Algirdas as a major fortified residence. It is considered the first all-stone castle in Belarus (or among the earliest fully stone ones in the GDL region, contrasting with prevalent wooden fortifications). Its strategic importance stems from its role in events like the 1385 Union of Krewo (Kreva Union), which initiated the Polish-Lithuanian union, the imprisonment and murder of Grand Duke Kęstutis (Keistut) in 1382, and Vitautis's (Vytautas) escape. The castle stands in a swampy floodplain valley at the confluence of the Krevlianka (or Servach) and Shlyakhtyanka rivers/creeks, surrounded by high hills at about 220 m elevation. Part of the structure rests on an artificially expanded sand dune for stability in the marshy terrain, leveraging the swamp as a natural defensive barrier (given the era's limited siege weaponry).

The exact construction date is undocumented, but estimates place it

in the late 13th to early/mid-14th century (second half of the 13th

to end of 14th). Some analyses (e.g., 1960s study by Lithuanian

architect Stasys Abramavskas) point to the 13th century based on

Baltic technical features; others link it to Gediminas (d. 1341) or,

more likely, his son Algirdas after ~1338. The first reliable

mention of the "Krev Stone" (stone castle) appears in late

14th/early 15th-century lists of cities. It replaced an earlier

wooden fortress.

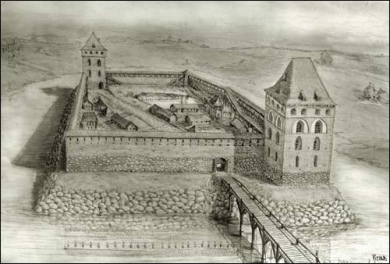

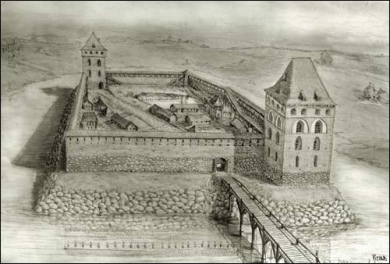

The layout formed an irregular trapezoid with

thick perimeter walls (2.5 m thick, up to 13 m high, foundations ~4

m deep) of local stone faced externally with brick. Two towers stood

at diagonal corners for optimal defense:

The larger

northwestern Princely (or Ducal) Tower protruded beyond the walls

(~20 m high originally, at least 3 stories): basement

dungeon/prison, second-floor princely quarters with wider windows

and painted ornaments, upper defensive level.

A smaller, purely

defensive tower (possibly added later).

The north-side

entrance led to a courtyard with residential/outbuildings, a pond

(western part), and a paved road between towers. Built partly on an

artificially expanded sand dune in swampy lowlands, the site

leveraged natural barriers (swamps, hills) against contemporary

siege weapons. It could shelter troops and civilians during raids.

Early History and Owners

Kreva (part of Nalšia, later a duchy

within the Grand Duchy) was an important residence for ruling

Gediminid dynasts. Gediminas granted it (with Vitebsk) to Algirdas

around his death in 1341; it remained a political center for

Algirdas and his sons (including Jogaila). It hosted

representational and residential functions more than pure military

ones initially.

Key Events

1382 (Lithuanian Civil War):

After conflict between Jogaila (Algirdas's son) and uncle Kęstutis,

Jogaila imprisoned Kęstutis (and initially cousin Vytautas) in the

Princely Tower's dungeon. Kęstutis died there within a week

(debated: natural causes or murder/strangulation by Jogaila's

order). Vytautas escaped, disguised as his wife's maidservant, and

fled to the Teutonic Knights. This deepened dynastic rifts.

14

August 1385 (Union/Act of Krewo): The pivotal prenuptial agreement

was confirmed/signed at Kreva Castle. Jogaila promised Polish

nobles/Queen Jadwiga's mother: personal and national conversion to

Roman Catholicism (and Christianization of pagan Lithuanians),

marriage to Jadwiga (Queen of Poland), payment of compensation to

end her prior betrothal to William of Austria, release of Christian

captives, recovery of lost Polish lands (e.g., Red Ruthenia), and

attachment (applicare) of Lithuanian/Ruthenian lands to the Polish

Crown. Sealed by Jogaila's brothers and Vytautas. This dynastic pact

enabled Jogaila's 1386 baptism (as Władysław II Jagiełło), marriage,

coronation as King of Poland, and laid the foundation for centuries

of Polish–Lithuanian union (evolving into the Commonwealth by 1569

via later unions like Lublin 1569). It also led to the first

Catholic parish/church in Kreva (~1387).

Later, Vytautas

occasionally stayed; it remained tied to the Algirdaičiai but lost

prominence. In 1432–1435 (civil wars between Švitrigaila and

Žygimantas Kęstutaitis), it was contested/sieged, with damage (e.g.,

to a tower in ~1433).

Decline, Destructions, and Later

History

Early 16th century: Sacked/burned by Crimean Tatars (and

possibly Russian forces); left unoccupied/abandoned for a long

period. By 1518, described as neglected in a small town.

18th–19th centuries: Still somewhat intact in the 18th, but walls

crumbled significantly by the 19th due to neglect.

World War I

(~1915–1918): Front line (Russian vs. German armies) near

Kreva/Smorgon; heavily shelled (hundreds of guns), used for

observation/shelters. Princely Tower and walls severely damaged;

ruins exacerbated.

Interwar (Polish control): Partial

conservation/restoration funded (e.g., 1929). Further decay in

Soviet era/WWII/postwar.

Recent Conservation, Archaeology,

and Status

Ongoing restoration since ~2017 aims to conserve four

walls, galleries, towers, and protect from weather (e.g., 2021: NE

wall and Princely Tower-adjacent section restored, gate installed;

reopened for visitors). Weekends feature excursions, workshops.

Archaeological expeditions (e.g., Institute of National History of

Belarus) continue to uncover details, such as 1433 siege damage or

refine chronologies.

Legends include an underground tunnel to

Vilnius and a maiden bricked alive in the walls. Nearby Yuryeva

Mountain has pagan temple remnants and protective boulders.

The ruins of the castle have survived to this day.

In 2005,

the local charitable foundation "Krevo Castle" was established, the

main goal of which is to contribute to the preservation of the Krevo

Castle. The Foundation annually organizes summer and cultural events

in Krevo and other settlements.

The castle is on the verge of

destruction. Some locals and tourists allow themselves to take out

ancient stones and bricks from the castle grounds. In 2018, work

began on the conservation of the Prince's Tower, in 2019/2020,

conservation with the restoration of the western wall, in 2020/2021

- the northern wall, along with the gate, were completed. In 2022,

it is planned to restore the southeastern wall of the castle. In

July, archaeological excavations were carried out at the foot of the

southwestern wall of the fortress. Fragments of Gothic semi-circular

tiles with spikes dating back to the 14th century, fragments of

tiles and pottery were found. The design of the restoration of the

Prince's Tower has already begun, in which it is planned to create a

museum.

The overall layout forms an irregular trapezoid (or irregular

quadrilateral) in plan, with walls enclosing a courtyard of notable

size capable of sheltering troops and civilians during raids.

Approximate wall lengths are: north ~85 m, east ~108.5 m, south

~71.5 m, west ~97.2 m. Two primary towers were positioned at

diagonal corners (northwest and likely southeast). A paved road

connected the towers inside. Recent archaeological work (2022–2023

excavations, prompted by conservation) uncovered evidence of a

possible third tower (foundations with wooden piles supporting stone

base), potentially altering prior understandings of the layout to

include more complex corner defenses.

The curtain walls were

2.5–3 m thick (commonly cited as 2.5 m), originally reaching 10–13 m

in height (often ~13 m), with foundations sunk ~4 m deep.

Construction used fieldstone (boulders/natural stone) for the lower

sections (up to ~3 m high), transitioning to brick for upper

portions or as facing ("faced with bricks outside"; upper sections

from ~7 m included a ~2 m belt of large bricks along the outer

perimeter; some descriptions note stone up to 3 m then brick

higher). This hybrid technique reflects Baltic regional medieval

practices. Walls included battle galleries (one burned in early

attacks, evidenced by stone cannonballs found in excavations). The

design emphasized defensive functionality over ornamentation,

similar to Lida Castle.

The two main towers (originally; possibly

three) provided key defensive and residential functions:

Princely (Great/Prince's/Ducal) Tower: Located at the northwest

corner, protruding outward beyond the main walls for enfilading fire

to defend the north and west sides simultaneously. Base nearly

square, ~18.65 × 17 m. Height estimated ~20 m (some accounts up to

25 m). At least 3–4 floors plus basement:

Basement/cellars:

dungeon/prison.

Lower/mid floors: princely living quarters with

wider, higher windows; walls painted with ornaments.

Upper

floor(s): purely defensive (battle positions).

Internal access

via passages/stairs within the thick walls.

This tower's

prominence made it a target; it suffered heavy damage.

Small

Tower: Smaller, ~11 × 10.65 m, at the opposite (southeast?) diagonal

corner. Primarily defensive (no residential features noted);

possibly a later addition. Some WWII-era modifications (e.g.,

pillbox) noted in restoration contexts.

Entrances included a

main gate on the southeast side; another reference notes a northern

entrance/gate (possibly a secondary or postern gate), with a road

leading from the Princely Tower to the north gate. A "Small Gate"

(restored recently in traditional arched style) has been highlighted

in conservation. The courtyard contained mostly wooden

residential/outbuildings (houses, forge), a pond (western part for

water supply), and possibly other utilitarian structures. A moat

(filled with water) is mentioned in some accounts surrounding the

exterior.

The castle endured sieges (e.g., failed Tatar/Russian

attempts in the 16th century, leading to rebuilds after 1503–1506

and 1519) but was largely abandoned by the early 19th century. It

was severely damaged in WWI (1914–1917): used by German forces, then

heavily shelled by Russian artillery (~800 guns, including naval

pieces) during the 1917 offensive, destroying much of the Princely

Tower, southern/eastern walls, and battle galleries. Earlier attacks

left traces like cannonballs. Interwar Polish preservation (1929

conservation), Soviet-era neglect, and further decay followed.

Today, it survives as evocative ruins: perimeter walls stand to

varying heights (fragments prominent), with partial remains of the

towers (Princely Tower most recognizable but ruined). No full

reconstruction; ongoing state-funded conservation (since ~2017/2018,

via presidential grants/budgets) focuses on stabilization against

weathering, precipitation, and prior damage. Phases include:

Princely Tower stabilization (2018), western wall (2019–2020),

northern wall + gate (2020–2021), north-eastern wall (2021), and

planned southeastern work. A "Small Gate" and related WWI/WWII

features (dugout, pillbox in Small Tower) are being restored

authentically. Plans include a museum in the Princely Tower. The

site is open to visitors with excursions.