Tel. 91- 454 88 00

Subway: Opera, Plaza de Espana

Bus: 3, 25, 33, 39, 148

Open: Apr- Sep: 9am- 6pm Mon- Sat, 9am- 3pm Sun & holidays;

Oct- Mar: 9:30am- 5 pm Mon- Sat, 9am- 2 pm Sun & holidays

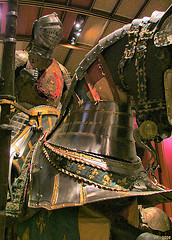

Palacio Real de Madrid or a Royal Palace of Madrid is one of the largest existing royal palaces in Europe. Its collection of art is truly an impressive. Priceless collection of masterpieces of Giovanni Battista Tiepoli, Luca Giordano, Caravaggio, Anton Mengs, Mariano Salvador Mael, Vicente Lopes and many others hang on walls. Additionally Palacio Real de Madrid has a large collection of Stradivarius violas, porcelain, clocks and medieval armor of knights. And all this is only part of the splendor concentrated here. In addition to splendor of Palace Real palace halls you can enjoy peace and quiet of the Royal Library, the Museum of Applied Arts and Royal Pharmacy. Behind the palace you can see beautiful gardens of Campo del Moro that were opened here in the 19th century.

Origins and Early History

The history of the Palacio Real de

Madrid, also known as the Royal Palace of Madrid, traces its roots

back to the 9th century during the Muslim rule of the Iberian

Peninsula. The site was originally a fortress constructed by Emir

Muhammad I of Córdoba between 860 and 880 AD as part of a defensive

system along the Manzanares River. This early structure, known as

the Alcázar, served primarily military purposes, protecting the

Muslim settlement of Mayrit (the precursor to modern Madrid). After

the Christian reconquest, particularly following the fall of Toledo

in the 11th century, the fortress transitioned into a royal

residence under the Castilian monarchs. King Henry III of Castile

(r. 1390–1406) added several towers in the 14th century, enhancing

its defensive capabilities, while his son John II (r. 1406–1454)

began using it more regularly as a palace.

During the late Middle

Ages, the Alcázar became a key stronghold for the Trastámara

dynasty. It played a significant role in the War of the Castilian

Succession (1475–1479), where troops loyal to Joanna la Beltraneja

were besieged there in 1476, resulting in substantial damage. The

only surviving medieval depiction of the structure is a 1534 drawing

by Flemish artist Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, which illustrates its

fortress-like appearance with towers and walls. Under the Habsburgs,

Emperor Charles V (r. 1516–1556) initiated major renovations in

1537, employing architects Alonso de Covarrubias and Luis de Vega to

modernize and expand the building, blending Renaissance elements

into the medieval core.

When Philip II (r. 1556–1598) designated

Madrid as the capital of Spain in 1561, the Alcázar gained even

greater prominence. He continued expansions, followed by his

successors Philip III (r. 1598–1621) and Philip IV (r. 1621–1665),

who added a long southern façade between 1610 and 1636. Despite

these improvements, the palace retained a relatively austere

Habsburg style, focusing on functionality over opulence. Philip IV's

reign marked a cultural high point, often called the Golden Age of

Spanish Art, during which he patronized artists like Diego Velázquez

and Francisco de Zurbarán. Although Philip IV's main artistic

project was the Buen Retiro Palace (built 1633–1640 under Count-Duke

Olivares), the Alcázar housed significant treasures and served as a

repository for royal collections.

Bourbon Era and the Great

Fire

The transition to the Bourbon dynasty in 1700 under Philip V

(r. 1700–1746), the first Bourbon king of Spain, brought French

influences inspired by Versailles. Philip V renovated the royal

apartments, enlisting architects Teodoro Ardemans and René Carlier,

while his queens—Maria Luisa of Savoy and later Elisabeth

Farnese—influenced the interior decorations. However, tragedy struck

on Christmas Eve 1734, when a devastating fire, believed to have

started in the rooms of court painter Jean Ranc, engulfed the

Alcázar. The blaze lasted four days, exacerbated by confusion over

alarm bells (mistaken for a call to midnight mass) and locked doors

to prevent looting. The fire destroyed the entire structure,

including priceless artworks, though some pieces like Titian's La

Dolorosa and Velázquez's Expulsion of the Moriscos were saved by

being thrown from windows.

Reconstruction and Architectural

Development

Philip V seized the opportunity to rebuild on a grand

scale, commissioning a new palace on the same site starting in 1735.

The design drew from Gian Lorenzo Bernini's unbuilt plans for the

Louvre, emphasizing Baroque grandeur with neoclassical elements.

Italian architect Filippo Juvarra (1678–1736) led the initial

project, proposing an enormous structure, but he died shortly after,

and his disciple Giovanni Battista Sacchetti (also known as Juan

Bautista Sacchetti) took over in 1736. Sacchetti simplified

Juvarra's vision to a more manageable square plan with a large

courtyard and projecting wings for panoramic views. Key

collaborators included Spanish architects Ventura Rodríguez,

Francesco Sabatini, and Martín Sarmiento.

Construction lasted

from 1738 to 1755, using durable materials like Colmenar stone and

granite to prevent future fires. Charles III (r. 1759–1788), Philip

V's son, was the first to occupy the palace in 1764, further

expanding it with Sabatini's additions, such as the southeast tower

(la de San Gil) and planned northern extensions (interrupted by

funding issues). The palace's façade features a rusticated base,

Ionic columns, and a balustrade adorned with statues of Spanish

kings and emperors, many relocated under Charles III for a more

classical aesthetic. Interiors boast lavish decorations, including

frescoes by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Corrado Giaquinto, and Anton

Raphael Mengs, and collections like the Royal Armoury (with armor

from Charles V and Philip II), porcelain rooms, and the only

complete Stradivarius string quintet in the world.

19th and

20th Century Transformations

In the 19th century, Ferdinand VII

(r. 1808–1833, with interruptions) undertook extensive renovations,

shifting from Italian to French neoclassical styles after his exile

in France during the Peninsular War. Alfonso XII (r. 1874–1885)

introduced Victorian elements, remodeling rooms with parquet floors

and new furniture under architect José Segundo de Lema (1879–1885).

The palace endured damage during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939),

requiring post-war restorations that reproduced lost elements.

Surrounding areas evolved too: The Plaza de la Armería was laid out

in 1892, facing the Almudena Cathedral (built 1879–1993). The Plaza

de Oriente, with its equestrian statue of Philip IV by Pietro Tacca,

was designed in 1844 by Narciso Pascual y Colomer. Gardens like the

Campo del Moro (expanded romantically under Isabella II) and

Sabatini Gardens (completed in the 1930s and opened in 1978) added

landscaped elegance.

During the Second Spanish Republic

(1931–1939), it was renamed Palacio Nacional and opened to the

public. Many artworks were transferred to the Prado Museum in the

19th century, but the palace retains significant collections,

including the Royal Library (with medieval codices) and Pharmacy

(dating to Philip II).

Modern Role and Significance

Today,

the Palacio Real is the largest functioning palace in Europe, with

135,000 square meters and 3,418 rooms, though the Spanish royal

family resides at the Zarzuela Palace. Owned by the state and

managed by Patrimonio Nacional, it serves mainly for state

ceremonies, such as the 2004 wedding banquet of Felipe VI and

Letizia Ortiz. Designated a Cultural Heritage Monument in 1931, it

symbolizes Spain's monarchical history, from Muslim fortress to

Bourbon splendor, reflecting shifts in power, art, and architecture

across centuries. Open to visitors (with fees, sometimes free), it

attracts millions, showcasing its enduring legacy as a testament to

Spain's imperial past and cultural wealth.

Exterior Architecture

The palace is laid out in a massive

square plan, organized around a central courtyard (Courtyard of

Honor) that serves as a grand parade ground. This layout creates a

sense of enclosure and introspection, with galleries lining the

inner perimeter. The principal façade, facing the Plaza de la

Armería (Armory Square) and opposite the Almudena Cathedral,

features projecting wings that extend forward, resolving sightline

issues and adding depth to the composition. Built on a granite base

with upper levels in white Colmenar limestone, the exterior

transitions from a rustic, robust lower story to more refined,

lighter upper floors, evoking a sense of ascension and nobility.

The façades are punctuated by a rhythmic arrangement of windows,

larger on the lower levels and diminishing in size toward the top,

framed by Ionic columns and pilasters that span multiple stories.

This colossal order unifies the elevation, while decorative elements

like balustrades, relief sculptures, and a prominent clock designed

by Sabatini adorn the roofline. The overall effect is one of

balanced grandeur, blending the exuberant curves and details of

Baroque with the orderly proportions of Neoclassicism. The palace's

position on a natural escarpment overlooking the Manzanares River

enhances its imposing presence, with the eastern façade opening onto

the Campo del Moro gardens.

Interior Architecture and Key

Spaces

Internally, the palace is a labyrinth of opulent rooms,

galleries, and service areas, totaling over 3,000 spaces across

multiple floors. The design accommodates royal living quarters,

administrative offices, and ceremonial halls, with a vertical

hierarchy: lower floors for utilitarian purposes, upper ones for

private and state functions. Vaulted ceilings dominate, ensuring

structural integrity and fire safety, while decorations evolve from

Baroque flamboyance under Philip V to more restrained Neoclassical

touches under Charles III and Ferdinand VII.

The Main Staircase,

designed by Francesco Sabatini, is a highlight: a grand

double-flight ascent with over 70 marble steps, flanked by lion

sculptures and frescoed ceilings depicting allegories of monarchy

and abundance. It leads to the piano nobile, the principal floor

housing state apartments.

Among the most celebrated rooms is the

Throne Hall (Salón del Trono), a Baroque masterpiece with a vaulted

ceiling frescoed by Giambattista Tiepolo, illustrating the

"Apotheosis of the Spanish Monarchy." The space features red velvet

walls, golden thrones, crystal chandeliers, and mirrors that amplify

its splendor, serving as the venue for royal audiences and

ceremonies.

The Gasparini Room, named after its designer Matteo

Gasparini, exemplifies Rococo influence with intricate stucco work,

silk wall hangings, and floral motifs in porcelain, embroidery, and

furniture. It functioned as a dressing room for Charles III,

blending functionality with artistic excess.

Other notable areas

include the Hall of Halberdiers (converted into a guards' room by

Charles III), adorned with tapestries and military motifs; the Royal

Chapel, a domed space housing a collection of Antonio Stradivari

string instruments and religious artworks; and the Royal Pharmacy,

with 18th-century cabinets, ceramic jars from La Granja factory, and

historical prescriptions. The palace also boasts extensive galleries

filled with masterpieces by artists like Caravaggio, Velázquez, and

Goya, as well as one of Europe's oldest preserved kitchens.

The

Hall of Mirrors, added by Charles IV, echoes Versailles with its

reflective surfaces and ornate details, while later additions under

Ferdinand VII include clocks, chandeliers, and furnishings that

enhance the eclectic interior.

Architectural Significance and

Legacy

The Palacio Real embodies the Bourbon dynasty's ambition

to modernize Spanish architecture, shifting from the austere

Habsburg style to a more international, enlightened aesthetic. Its

fireproof design, monumental scale, and integration of art with

architecture make it a pinnacle of 18th-century European palace

building. Expansions by Sabatini, including the southeast wing,

further refined its Neoclassical elements, ensuring harmony with

surrounding structures like the cathedral. Today, it remains a

symbol of Spanish heritage, blending historical layers into a

cohesive architectural narrative.