Location: Doune, Stirling Map

Constructed: late 14th century

Tel. 01786 841742

Open: Apr- Sep: 9:30am- 5:30pm daily

Oct- Mar 9:30am- 4:30pm Sat- Wed

(last admission 30 minutes before closing)

Closed: 21 Dec- 8 Jan

Doune Castle, perched above the River Teith in Stirlingshire, Scotland, is a formidable medieval stronghold that encapsulates centuries of Scottish history, architectural evolution, and cultural significance. Built in the late 14th century, it served as a noble residence, military fortress, and royal retreat, surviving wars, rebellions, and changing fortunes to become one of Scotland’s best-preserved castles. Its fame extends beyond history, thanks to its starring role in films like Monty Python and the Holy Grail and TV series such as Outlander and Game of Thrones. Managed by Historic Environment Scotland, Doune remains a captivating site, blending rugged stonework with evocative ruins and lush surroundings.

Origins and the Albany Stewarts (Late 14th Century)

Doune Castle was constructed around 1380–1400 by Robert Stewart, Duke of

Albany (c. 1340–1420), a towering figure in medieval Scotland. As the

third son of King Robert II, Albany wielded immense power as Governor of

Scotland, effectively ruling during the reigns of his father, brother

(Robert III), and nephew (James I). The castle replaced an earlier

fortification, possibly Roman or Dark Age, on the site, chosen for its

strategic position controlling routes between Stirling, the Highlands,

and the Lowlands.

Albany built Doune as both a power base and a

luxurious residence, reflecting his near-royal status. Its robust

defenses signaled military might, while its spacious halls catered to a

grand household. After Albany’s death in 1420, his son Murdoch inherited

the castle, but the family’s fortunes collapsed in 1425 when James I,

freed from English captivity, executed Murdoch and his sons for treason,

seizing Doune for the crown.

Royal and Noble Tenure (15th–16th

Century)

As a royal castle, Doune hosted Scotland’s monarchs, notably

James I and Mary of Guelders, widow of James II, who died there in 1463.

It served as a dower house for queens, including Margaret Tudor, wife of

James IV, who held it after his death at Flodden (1513). The castle’s

defenses were tested during this period, though no major sieges are

recorded, reflecting its deterrent strength.

By the late 16th

century, the crown granted Doune to the Stewart Earls of Moray,

descendants of James V’s illegitimate son. James Stewart, the “Bonnie

Earl” of Moray, resided there until his murder in 1592 by the Gordons, a

feud immortalized in the ballad The Bonnie Earl o’ Moray. His widow,

Lady Agnes, maintained the castle, which passed through the Moray line,

hosting occasional royal visits, such as James VI’s stays.

Jacobite Rebellions and Decline (17th–18th Century)

Doune’s military

role resurfaced during the Jacobite Rebellions. In 1689, during the

first uprising, government troops garrisoned it against Highland clans

supporting James VII. The castle saw action again in the 1715 Rebellion,

with repairs made to house prisoners. Its most dramatic moment came

during the 1745 Rebellion, when Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Jacobites

captured Doune, imprisoning Hanoverian soldiers in its cellars. After

their defeat at Culloden (1746), government forces retook it, detaining

Jacobite prisoners, some of whom escaped via a latrine chute.

By

the late 18th century, Doune’s strategic value waned. The Moray family,

focused on other estates like Darnaway, neglected it, and the roof

collapsed around 1800, leaving the castle a ruin. Romanticized as a

relic, it drew early tourists, including Sir Walter Scott, who admired

its “grim grandeur.”

Restoration and Modern Era (19th

Century–Present)

In 1883, the 14th Earl of Moray began restoration,

reroofing the castle to preserve its structure. His successors continued

maintenance, and in 1984, the Moray family leased Doune to the state,

now managed by Historic Environment Scotland. Partial repairs, like

stabilizing the gatehouse, ensure accessibility, though much remains

evocatively unrestored.

Doune’s modern fame stems from its screen

appearances. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) used it as multiple

locations—Castle Anthrax, Swamp Castle, and more—its courtyard

immortalized in the coconut-shell “horse galloping” scene. Outlander

(2014–present) cast it as Castle Leoch, home of Clan Mackenzie, while

Game of Thrones (2011) featured it as Winterfell in its pilot. These

roles boost tourism, with visitors flocking to reenact scenes or explore

its history. As of April 11, 2025, Doune remains a vibrant site, hosting

events like medieval reenactments and Outlander-themed tours.

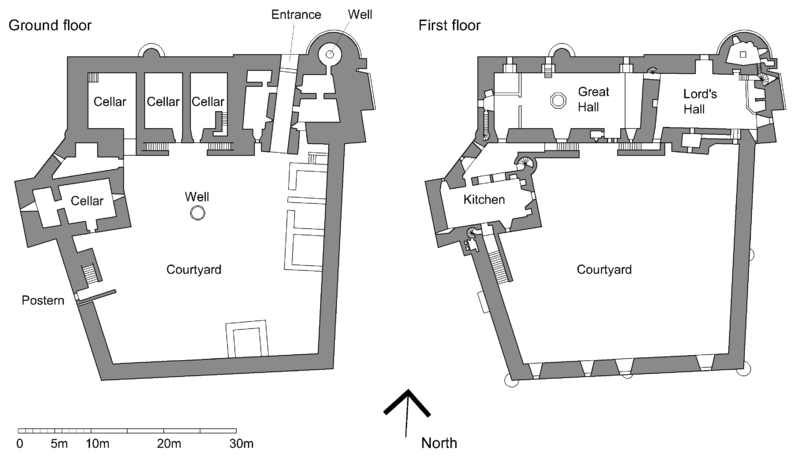

Doune Castle is a courtyard castle, its L-shaped layout combining

defense with domesticity. Built of local sandstone, its walls rise

sheer from a grassy mound, flanked by the River Teith and Ardoch

Burn, enhancing natural defenses. The castle’s intact state—rare for

its age—offers a vivid snapshot of 14th-century architecture.

Gatehouse Tower

The gatehouse tower, dominating the north

front, is Doune’s most striking feature:

Rising 25 meters (80

feet), it houses the lord’s residence across four floors.

A

vaulted entrance passage, once secured by a portcullis and double

doors, leads to the courtyard. Above, a first-floor Lord’s Hall (14

x 7 meters) boasts a double fireplace, window seats, and a carved

oak screen, reflecting Albany’s wealth. A private chamber and

latrine adjoin, with a trapdoor to a bottle-shaped dungeon below.

Upper floors include a guest chamber and a small treasury room,

accessible via spiral stairs. The battlements, restored in the 19th

century, offer panoramic views of Ben Lomond and Stirling.

Shot-holes and arrow slits underscore its defensive role, though

large windows suggest confidence in its deterrent power.

Great Hall and Kitchen Tower

The Great Hall, forming the castle’s

eastern range, is a masterpiece of medieval design:

Measuring 20

x 8 meters, it sits above vaulted cellars, reached by a broad stair

from the courtyard. Its timber roof, restored in 1883, spans a space

lit by tall windows, with a minstrels’ gallery and a central hearth

(now floored over).

A serving hatch connects to the kitchen

tower, a cylindrical block with a massive fireplace (3 meters wide)

for roasting oxen, a baking oven, and a slop drain. A servery and

pantry link to the hall, supporting feasts for hundreds.

The

kitchen’s upper floors housed staff or lesser guests, with a spiral

stair to the battlements.

Courtyard and Ancillary Structures

The courtyard, roughly 30 x 25 meters, is enclosed by high curtain

walls, largely intact:

A well, 14 meters deep, supplied water,

vital during sieges.

Timber ranges, now gone, once lined the

walls, housing stables, a brewhouse, and servants’ quarters. Their

stone footings remain.

A postern gate near the kitchen tower

allowed discreet access to the river, possibly for supplies or

escape.

The castle’s design prioritizes self-sufficiency,

with storage for grain, wine, and ale in cellars, and ovens for

daily bread. Its layout—centralized yet fortified—reflects Albany’s

need to project power while hosting allies.

Condition and

Restoration

Unlike many Scottish castles, Doune escaped heavy

bombardment, preserving its core structure. The 1883 reroofing saved

the interiors, though weathering has softened details like window

tracery. The dungeon, cellars, and upper chambers remain

atmospheric, with graffiti from 18th-century prisoners adding

character. Ongoing maintenance, funded by Historic Scotland and

visitor revenue, ensures stability, though some areas, like the

battlements, are periodically closed for safety.

Doune’s setting enhances its allure:

Natural Defenses: The castle

sits on a low ridge, with the Teith to the west and Ardoch Burn to the

south, creating a moat-like barrier. Marshy ground once deterred siege

engines.

Landscaping: The immediate grounds are simple—grassy slopes

and a gravel path—but the surrounding estate, still Moray-owned,

includes woodlands and fields. A short walk along the Teith leads to

Doune village, with its 19th-century pistol factory and bridge.

Views: From the battlements, visitors see Stirling Castle (8 miles

east), the Ochil Hills, and Highland peaks, tying Doune to Scotland’s

broader landscape.

No formal gardens survive, unlike Dirleton

Castle, but the castle’s stark beauty needs little adornment. A small

ticket office and shop sit outside, minimizing intrusion.

Doune Castle embodies medieval Scotland’s power dynamics and cultural

shifts:

Political Hub: As Albany’s seat, it hosted negotiations and

feasts, shaping Stewart dominance. Its royal use under queens like

Margaret Tudor underscores its prestige.

Jacobite Legacy: The 1745

imprisonment of Hanoverians and Jacobites ties Doune to Scotland’s

divided loyalties, with escape tales adding folklore.

Literary

Echoes: Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley (1814), set partly in a

fictionalized Doune, cemented its Romantic image, inspiring 19th-century

tourism.

Screen Icon: Monty Python made Doune a cult destination,

with fans quoting “Your mother was a hamster!” in its courtyard.

Outlander and Game of Thrones deepened its global reach, portraying it

as a clan stronghold or northern fortress, blending history with

fantasy.

Community Anchor: Doune village (pop. 2,200) thrives on

castle tourism, with local pubs like the Woodside Hotel serving

Outlander-themed drams. Annual events, like medieval fairs, draw

families.

The castle’s versatility—fortress, palace, prison,

ruin, and film set—mirrors Scotland’s own adaptability, making it a

cultural touchstone.

Located 8 miles northwest of Stirling off the A84, Doune is

accessible by car (free parking) or bus (routes 59, X10A from Stirling,

20-minute ride). Doune railway station, 1 mile away, connects to

Edinburgh (50 minutes). Opening hours are:

April 1–September 30:

Daily, 9:30 AM–5:00 PM (last entry 4:30 PM).

October 1–March 31:

Daily, 10:00 AM–4:00 PM (last entry 3:30 PM).

Admission (2025

rates) is £10 for adults, £6 for children (5–15), free for Historic

Scotland members, and half-price for English Heritage/Cadw members

(booking advised). An audio guide, narrated by Monty Python’s Terry

Jones and Outlander’s Sam Heughan, adds humor and context, covering

history and filming anecdotes.

The castle is largely accessible,

with a level courtyard and ground-floor rooms, though spiral stairs to

the Lord’s Hall and battlements (74 steps) challenge mobility-impaired

visitors. Children delight in exploring cellars and reenacting Monty

Python scenes, but parents should mind steep drops. Dogs are allowed in

the grounds (leashed, not indoors). A picnic area by the Teith suits

families, and the shop sells Holy Grail-inspired coconut shells.

Visitors can wander the Great Hall, peer into the dungeon, or climb to

the battlements for Highland views. Nearby attractions include Stirling

Castle, the Wallace Monument, and Blair Drummond Safari Park, making

Doune a hub for Central Scotland exploration.

Doune faces preservation hurdles typical of medieval sites:

Weathering: Rain and frost erode sandstone, particularly window sills

and parapets, requiring regular repointing.

Tourism Pressure: Film

fame draws 70,000+ visitors yearly, straining paths and facilities.

Historic Scotland caps group sizes to protect interiors.

Funding:

Maintenance relies on ticket sales and memberships, with budget

constraints limiting full restoration of minor structures like the

brewhouse.

Recent efforts include drainage improvements (2023) to

prevent cellar flooding and safety checks on the gatehouse. Climate

change, increasing rainfall, prompts long-term planning, like

reinforcing riverbanks. Doune’s lease to Historic Scotland ensures Moray

family involvement, balancing heritage with public access.