Location: Rievaulx, North Yorkshire Map

Tel. 01439 798228

Active: 1132- 1538 (closed by Henry VIII)

Open:

Apr-Sep: daily 10am-6pm

Oct: Thu-Mon 10am-5pm

Nov-Mar:

Thu-Mon 10am-4pm

Closed: 24- 26 Dec, 1 Jan

Cost: £5.30 adults, £2.70

children

Rievaulx Abbey is a medieval Roman Catholic monastery of the Cistercian order situated in Rievaulx, North Yorkshire in United Kingdom. Rievaulx Abbey was found in 1132 by 12 monks who were blessed by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux to leave their home in Clairvaux in France to move to the island. New abbey of the White Monks served as their base for missionary work in the North England as well as Scotland regions. Help from benefactors such as Henry II (1135-1154) and King David of Scotland (1124-1153) further increased wealth and influence of the Rievaulx Abbey. At some point it numbered over 150 monks and over 500 lay brethren. A big influence on the prestige and fame of the monastery came when its third abbot Aelred took charge of the community. Famous author and an inspiration preached he attracted many people to the abbey and after his death was canonized by the church.

The abbey ruins lie in a wooded valley near the River Rye near Helmsley in North Yorkshire. Today the area is part of the North York Moors National Park.

Foundation (1132)

The abbey was established in March 1132,

marking it as the first Cistercian monastery in northern England. It

was founded by a group of 12 monks from Clairvaux Abbey in France,

led by Abbot William, on land donated by Walter Espec, the lord of

nearby Helmsley and a royal justiciar who supported ecclesiastical

reforms. Espec, along with Thurstan, Archbishop of York, aimed to

promote the Cistercian ideals of simplicity and isolation, drawing

from the order's origins at Cîteaux in 1098. The site's remote,

wooded location—sheltered by hills—was ideal for a life of prayer

and self-sufficiency, with minimal external contact. Initial

structures were temporary wooden buildings, but stone construction

began in the late 1130s around a central cloister. The monks even

diverted the River Rye multiple times during the 12th century to

create flat building land, with traces of the old river course still

visible today.

Growth and Peak Period (12th–13th Centuries)

Under Abbot William, the abbey quickly expanded, dispatching monks

to establish daughter houses such as Warden and Melrose in 1136,

Dundrennan in 1142, and Revesby in 1143, effectively colonizing

northern England and Scotland. By the 1160s, the community had grown

to around 650 members, including 140 choir monks and 500 lay

brothers who handled manual labor.

The abbey's zenith came under

Saint Aelred, elected abbot in 1147. Aelred, previously a steward in

the household of David I of Scotland, was a prolific writer,

biblical scholar, and Latin stylist whose works on spirituality

influenced medieval thought. During his tenure until 1167, the

population doubled, and major architectural projects were

undertaken, including a monumental church started in the late

1140s—one of Europe's earliest great mid-12th-century Cistercian

churches—and a unique chapter house design. Aelred also oversaw the

reconstruction of the east range for choir monks, his personal

lodging, a large infirmary hall, and a novitiate around a second

cloister. By the end of his leadership, Rievaulx had five daughter

houses and had become one of Britain's most powerful and spiritually

renowned monastic centers.

Successor abbots like Silvanus

(post-1167) continued expansions, rebuilding the south range and

completing cloister arcades in the 1170s, while extending the church

in the 1220s to house Aelred's shrine. However, financial strains

emerged by the 1220s–1230s, leading to Abbot Roger II's resignation

in 1239 amid incomplete transept remodeling.

Architectural

Developments

Rievaulx's architecture evolved in phases,

reflecting Cistercian ideals while adapting to growth. The early

12th-century layout featured a cloister with ranges for monks and

lay brothers; surviving elements include the northern west range and

south range fragments. The church, begun under Aelred, included a

presbytery in the Early English style, while the 13th-century

refectory spanned a valley slope with an undercroft. By the late

Middle Ages, adaptations included partitioning the lay brothers'

dormitory into private closets, filling nave aisles with chapels,

and demolishing the lay refectory. At its dissolution, the site

encompassed 72 buildings.

Economic Activities and Daily Life

Economically, Rievaulx prospered through agriculture, sheep rearing,

wool trade to Europe, and mining lead and iron ore, amassing 6,000

acres of land. It operated a water-powered forge for iron tools and,

remarkably, a prototype blast furnace at Laskill, one of the

earliest in England. Daily life adhered to strict Cistercian rules:

choir monks focused on prayer and study, while lay brothers managed

labor until their decline in the 14th century, after which hired

workers were employed. By the 15th century, practices relaxed,

allowing meat consumption and private accommodations in the former

infirmary.

Decline and Challenges (14th–16th Centuries)

Decline set in during the late 13th century with sheep scab

epidemics reducing revenue, followed by Scottish raids in the early

14th century. The Black Death in the mid-14th century decimated the

population, leaving only 14 choir monks, three lay brothers, and the

abbot by 1381. This led to land leasing and building reductions.

Internal conflicts arose, such as the ejection of Abbot Edward

Cowper in 1533 due to leadership disputes. By 1538, only 23 monks

remained, with an annual income of £351.

Dissolution (1538)

As part of Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–1540),

Rievaulx was suppressed on December 3, 1538. The site was sold to

Thomas Manners, 1st Earl of Rutland, who dismantled buildings,

stripping valuables like roof lead and bells for the Crown. The

process was documented by steward Ralf Bawde, rendering the

structures uninhabitable.

Post-Dissolution History

Post-dissolution, the site shifted to industry: by 1545, four iron

furnaces operated, using the refectory undercroft for charcoal

storage. A blast furnace was added in 1577, and a new forge in

1600–1612, but operations ceased in the 1640s due to timber

shortages. In 1687, the estate was sold to Sir Charles Duncombe, who

developed Duncombe Park. By the 1750s, a terraced walk with Grecian

temples overlooked the ruins, now managed by the National Trust.

From the 1770s, the site drew Romantic artists and writers. In the

mid-19th century, its architectural value was recognized, leading to

guardianship by the Office of Works in 1917. Repairs in the 1920s

used reinforced concrete, and World War I veterans cleared debris,

exposing buried features. In 1923, salvaged lead was donated to

restore York Minster's Five Sisters window.

Current Status

Today, Rievaulx is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and tourist

attraction under English Heritage, with public access to substantial

ruins. Archaeological surveys in 2015 and 2018, including aerial

photography, have enhanced understanding of the landscape, with

findings published in 2019. The site's cultural legacy endures,

notably in the title Baron Wilson of Rievaulx adopted by former

Prime Minister Harold Wilson in 1983.

Rievaulx Abbey, located in a secluded wooded valley along the River

Rye in North Yorkshire, England, was founded in 1132 as the first

Cistercian monastery in northern England. The site's natural

topography, sheltered by surrounding hills, influenced its

architecture significantly. To create sufficient flat land for

construction, the monks diverted the river's course multiple times

during the 12th century, demonstrating early engineering ingenuity.

At its peak, the abbey housed around 140 choir monks and 500 lay

brothers, making it one of the wealthiest Cistercian houses in

England, with extensive lands supporting agriculture, sheep farming,

and mining. The architecture reflects Cistercian ideals of austerity

and self-sufficiency, evolving from simple Romanesque forms to more

elaborate Early Gothic elements over time. Today, it stands as one

of the most impressive monastic ruins in Britain, preserved under

English Heritage since 1917.

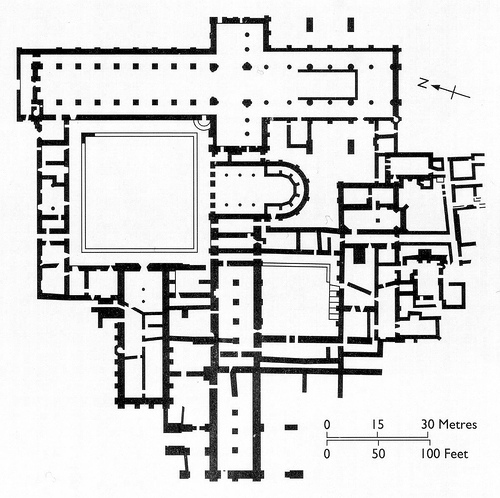

Overall Layout and Site Planning

The abbey's layout followed the standard Cistercian plan, centered

around a cloister that served as the heart of monastic life. The

cloister was a square courtyard with covered walkways (arcades) on

all sides, providing access to key buildings. To the north lay the

abbey church, the largest and most prominent structure. The east

range housed facilities for the choir monks, including the chapter

house, sacristy, and dormitory. The south range contained the

refectory (dining hall) and warming house, while the west range was

originally dedicated to lay brothers, with their own refectory and

dormitory. An additional infirmary cloister was built to the east,

including an infirmary hall and novitiate.

The precinct extended

beyond the core buildings, encompassing water-management features

like canals and mill races for powering forges and mills, as well as

agricultural enclosures. By the time of its dissolution in 1538, the

abbey complex included 72 buildings, though many were reduced or

repurposed due to declining populations after events like the Black

Death in the 14th century. Archaeological surveys in 2015 and 2018

have revealed the broader landscape, including outer precinct walls

and ancillary structures for ironworking.

The Abbey Church:

Core of the Architectural Splendor

The church, begun in the late

1140s under Abbot Aelred (1147–1167), is the abbey's architectural

highlight and one of the earliest major Cistercian churches in

Europe. It measures approximately 350 feet in length, with a

cruciform (cross-shaped) plan typical of medieval ecclesiastical

architecture. The nave, originally divided into sections for choir

monks and lay brothers, features a series of pointed arches

supported by clustered columns, transitioning from Romanesque

rounded arches in the earlier western sections to Early Gothic

pointed ones in the east.

The presbytery, rebuilt in the 1220s,

exemplifies Early English Gothic style with its soaring three-storey

elevation, lancet windows, and ribbed vaulting (though now

roofless). This extension added seven bays, housing chapels and a

shrine to St. Aelred, and stands as one of the finest examples of

Early Gothic in northern England. The transepts were partially

remodeled during this phase, with upper levels and eastern chapels

rebuilt, but financial constraints halted a full renovation. The

church's interior would have been plain, adhering to Cistercian

prohibitions on ornate decoration, though subtle moldings and

capitals add elegance.

In the later Middle Ages, as lay brothers

dwindled, the nave's aisles were infilled with chapels, and the

central space was used for processions. Post-dissolution dismantling

removed roofs, lead, and bells, leaving the dramatic skeletal ruins

visible today.

The east end, with its towering window frames,

offers a sense of the original height—over 40 feet in

places—emphasizing verticality to draw the eye heavenward, a

hallmark of Gothic design.

Cloisters and Associated Ranges

The main cloister, rebuilt on a

grand scale during Aelred's tenure, featured a central open

courtyard surrounded by arcades with simple columns and arches. The

east range was expanded to accommodate the growing monastic

community, including a revolutionary chapter house design. This

polygonal chapter house, unique among Cistercian sites, included an

ambulatory aisle allowing lay brothers to attend sermons without

entering the monks' inner space. It was used for daily readings from

the Rule of St. Benedict and community meetings.

The south

range's refectory, constructed in the 1170s, was elevated over a

massive undercroft to level the sloping valley site. This two-storey

structure, with its high vaulted ceiling and rows of windows, could

seat hundreds and included a pulpit for readings during meals. The

undercroft later served as storage for charcoal in the post-monastic

ironworks era. The west range, for lay brothers, included a large

refectory (later demolished) and dormitory, which was halved and

partitioned in the 14th century as their numbers declined.

An

eastern infirmary cloister provided separate facilities for the ill,

with a hall, kitchen, and abbot's lodging—reflecting adaptations for

comfort in later periods.

Architectural Styles and Evolution

Rievaulx's architecture evolved from the austere Romanesque of its

founding phase (late 1130s) to the lighter, more expressive Early

Gothic by the mid-12th century. Initial buildings under Abbot

William used simple, unadorned stonework with rounded arches and

thick walls, embodying Cistercian simplicity. Under Aelred,

influences from Burgundian Cistercian models introduced pointed

arches and taller elevations, blending functionality with emerging

Gothic trends for increased light and height.

By the 1220s, the

presbytery's rebuild marked a peak in sophistication, with clustered

piers, molded arches, and a shrine integration that anticipated

later Gothic developments. Later modifications in the 14th–15th

centuries reflected declining austerity: private cells for monks,

meat allowances, and hired labor replacing lay brothers, leading to

structural reductions like truncating the west range. This shift

mirrored broader changes in Cistercian life toward comfort.

Materials and Construction Techniques

The abbey was primarily

built from local sandstone, quarried nearby, which provided

durability but also contributed to the warm, honey-toned appearance

of the ruins. Stone was laid in ashlar blocks for key facades, with

rubble cores for walls. Construction involved advanced techniques

for the era, such as river diversion for site preparation and the

use of water power for mills. The site's slope necessitated

undercrofts and terracing, as seen in the refectory. Lead roofing

and iron fittings (from on-site forges) were common, though stripped

after the 1538 suppression. A prototype blast furnace at nearby

Laskill, operational by the 15th century, highlights the abbey's

industrial integration with architecture.

Notable Features

and Historical Modifications

Key features include the chapter

house's innovative aisle, the presbytery's shrine (now lost), and

the extensive water systems. Post-1538, the site was repurposed for

ironworking, with forges and furnaces added, altering some

structures like the refectory undercroft. In the 1750s, Thomas

Duncombe III created Rievaulx Terrace overlooking the ruins, with

neoclassical temples, blending romantic landscape design with the

medieval remnants. Preservation in the 20th century involved

reinforced concrete beams by Sir Frank Baines to stabilize walls,

and debris clearance revealed buried features without major

excavations.

Current State as Ruins

As ruins, Rievaulx

offers a poignant glimpse into medieval monastic architecture. The

church's nave arcades and presbytery walls dominate, with grass

floors evoking the open sky that replaced vaulted roofs. English

Heritage maintains the site, with a museum displaying artifacts like

carved stones and ironwork. The abbey's significance lies in its

scale, stylistic evolution, and role in Cistercian history, making

it a UNESCO World Heritage candidate as part of Yorkshire's monastic

ensemble.