Location: 3 mi (2 mi) West of Amesbury, Wiltshire Map

Construction: 2500 BC

Info: 01980 622833

Open: Apr & May:

9:30am- 6pm

Jun- Aug: 9am- 7pm

Sep & Oct: 9:30am- 6pm

Nov- Mar:

9:30am- 4pm

Closed: 20- 22 June, 24- 25 Dec

www.english-heritage.org.uk

Stonehenge is a Neolithic structure built over 4,000 years ago and

used at least until the Bronze Age near Amesbury, England.

It

consists of a ring-shaped mound of earth, inside which are various

formations of worked stones grouped around the centre. They are called

megaliths because of their gigantic size. The most striking of them are

the large circle of formerly 30 standing cuboids, which originally had a

closed ring of 30 capstones on their upper side, and the large

horseshoe, originally made of ten such columns, which were connected in

five pairs by a capstone. the so-called triliths. Within each of this

horseshoe and circle stood two figures similar in form: both of much

smaller, but formerly twice as many, stones.

These four

formations are complemented by the "Altar" near the center of the

complex, the so-called "Sacrificial Stone" within - and the Heelstone

well outside the northeast exit. In addition, three concentric circles

of holes were created in the ring wall and in the largest of them four

menhirs were arranged in a rectangle, the short sides of which lie

parallel to the longitudinal axis of the monument. Other buildings from

the megalithic era - especially burial mounds and two structures that

are called racecourses - can be found in the area. In addition, there

are the remains of the so-called Processional Way, which extends from

the said exit to the right to the banks of the Avon. The radius, which

leads downwards into the entrance of the monument, then points in its

extension to the south coast of England, about 50 km away;

interestingly, exactly where the rivers Avon and Stour join the English

Channel (see Christchurch Harbour). According to this, there could have

been processions that on certain days began in the morning in a

north-easterly direction, followed the apparent path of the sun down

towards the coast and ended in the evening, returning via the entrance

to the monument.

Recent research suggests that Stonehenge - and

with it the culture that built it - should not be viewed in isolation

from similar structures. At the point where the Processional Way meets

the Avon lies the smaller Bluehenge. There may also be a connection with

the nearby construction of Durrington Walls or a motive common to the

various peoples that led to the development of megalithic cultures.

There are various hypotheses, some of which complement one another

and some of which contradict one another, about the occasion and

ultimate purpose of this complex, which was designed to be extremely

complex. They range from the self-portrait of a primal-political

alliance of two formerly hostile tribal organizations (see double

execution of the formations and the size hierarchy of the menhirs) to a

religious burial or cult site to an astronomical observatory including a

calendar for the sowing and harvest times.

All of these

hypotheses, including the more purely speculative ones, agree on one

point: the architects of the monument succeeded in aligning the

horseshoes and the stones placed vertically in front of their openings

exactly with the sunrise at that time on the day of the summer solstice.

The path from the simplest to the most complex, final version of

this system can be divided into at least three sections:

The

beginning of the first phase, during which a circular mound with a

surrounding ditch was built, is dated to about 3100-2900 cal B.C. and

lasted until about 2900–2600 cal B.C. (or even up to 2100 BC).

The

second phase with the Aubrey Holes as the largest of the three circles

of holes mentioned above, plus other holes outside the ring wall, dating

from the first half of the third millennium BC, lasted until about

2500/2400 cal B.C. (or until 2000 BC).

Stone constructions were built

from around 2400 to 1500 BC. B.C., whereby the following explanations

radically changed the earlier ones several times.

According to

the first vague indications, the beginnings of the complex as an actual

megalithic monument go back much further than previously assumed; it

seems so already around 3000 BC. to have given a first version of stone

structures. However, the further statements in this article refer to the

dating that has so far been assumed to be certain.

The latest

research suggests that the place where the remains of the monument can

be viewed today had a special ritual significance for people 11,000

years ago.

The monument has been owned by the English state since

1918; It is managed and developed for tourism by English Heritage, and

its surroundings by the National Trust. UNESCO declared the Stonehenge,

Avebury and Associated Sites a World Heritage Site in 1986.

In

2019, Stonehenge was visited by 1.6 million people.

The name Stonehenge is already attested in Old English as Stanenges

or Stanheng. While the first part of the name is the Old English word

stān "stone", there is uncertainty about the second element. It could be

hencg "angel, hinge" or a substantive derivation from the verb hen(c)en

"to hang", which would then mean "gallows". In fact, medieval gallows

had two feet and thus resembled the triliths in the center of the

monument. The attempted interpretation as "stones hanging (in the air)"

lacks semantic consistency.

The second part of the name, Henge,

is now used as an archaeological term for that class of Neolithic

structures consisting of a ring-shaped raised enclosure with a ditch

running along the inside. Stonehenge itself is what is known as an

atypical henge in current terminology, as the moat lies outside the ring

wall.

The complex was continuously changed or built in several

phases. These activities extend over a period of about 2000 years.

However, the site was demonstrably in use before the first stone

construction. Three large putative postholes located outside the ring

wall near the present car park date from the Mesolithic period, around

8000 BC. The remains of cremations dating back to between 3030 and 2340

BC were found in soil samples around the place of worship. were dated.

As a result, the site was already in use as a burial ground before the

stones were set up. The most recent cultic activities (druids, emergence

of the Avalon saga?) date from around the 7th century AD, and the tomb

of a decapitated Anglo-Saxon is worth mentioning as an artefact.

It is difficult to date the various phases in the design of the monument

and to understand their meaning, since earlier excavation methods did

not meet today's standards and there are still hardly any theories that

would allow one to empathize with the thoughts and actions of the people

of that time .

So remains u. unsure what the function of the

holes found in the ground was. Some scholars contend that their original

purpose was to accommodate buttresses for the purpose of a no less

speculative roofing of the square. Others argue that such hypothetical

tribes were phallic symbols or totem poles that were later replaced by

towering rocks as technological advances and cultural-demographic

changes such as population growth and the consequent increase in labor

force increased.

Cognitive archaeologist Colin Renfrew suggested

that such constructions were intended to impress the viewer from a

distance, i. i.e. to make enemies think twice about attacking. The

gradual expansion of the facilities is thus interpreted as a symbolic

'arms race' among neighboring tribes - possibly as an expression of the

'phallic threat', as it could often have been preserved as a genetic

disposition to this day. This thesis is supplemented by the assumption

that the structures of Stonehenge, which ultimately changed again and

again in the direction of increasing complexity, reflect memories of the

course of military conflicts, including the displacement of an

indigenous population that had been stronger in number in the meantime.

Such a process could be reflected in the temporarily completely (?)

removed bluestones from the ring wall. The fact that this culture was

ultimately included in the dominion of the victors despite being

inferior – the latter sometimes expressed their being through the two

sarsen formations built from fundamentally much larger stones – would

then correspond to the result of a territorial dispute that was peaceful

, with the founding of a new (mixed) culture.

The fact that only

little material has been discovered so far from which 14C data could be

obtained makes it even more difficult to understand the development of

these cultures over time, and thus also the gradual changes to the shape

of the monument that were only discovered archaeologically. The sequence

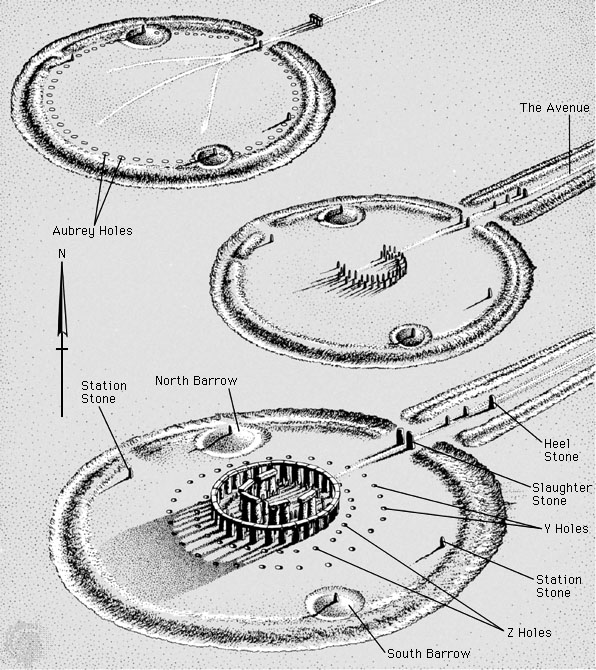

of these interventions, which is mostly accepted today, is explained in

the following text with reference to the map sketch shown. The megaliths

that have survived to the present are highlighted by coloring their

outlines (blue, brown and black); the capstones of the two sarsen

formations were left out for reasons of clarity and there is speculation

about the disappearance of the rest of the heavily damaged complex. The

monument was partly used during the feudal phase of England as a quarry

for the construction of churches, fortresses and palaces of the

powerful, but there are also clear traces of targeted destruction.

Carefully dismembered columns, shattered images, etc., modern archeology

mostly interprets in terms of the annihilation of a culture by the

succeeding victors; parallel it appears from about 1400 cal B.C. to have

come to a change in burial customs (from megalithic communal tombs to

tombs for individual rulers), which can also be interpreted in this way.

The heelstone and sacrificial stone, and with them the openings of

the two central horseshoes, were aligned with the position of midsummer

sunrise; also, among others, the four stones of the rectangular

structure on the ring wall seem to have something to do with different

periodicities of celestial mechanics. For these reasons, Stonehenge is

often assumed to have been an ancient observatory, although the precise

nature of its use and its importance, such as for sowing and reaping at

the best possible times (see below), are still debated.

Description of the stones (from inside to outside)

The Altar Stone: A

five meter block of green sandstone closest to the center of the

complex.

Next to that is the small horseshoe: it housed 19 stones

made of dolerite, a very hard basalt from the Preseli Mountains in South

West Wales. Because of their bluish shimmer, the megaliths made of this

material are also known as blue stones. Their height reaches up to 2.8 m

(towards the open legs of the horseshoe it decreases to 70 cm), and

their shape is cylindrical, not conical like the otherwise widespread

obelisks. A distinctive feature is that the two menhirs to the left and

right of the base stone of this horseshoe show a cross-section that

corresponds to the geometry of a tongue and groove connection from the

carpentry trade. However, a concrete, mechanically connecting task of

both forms can be ruled out, because the stones are a good 3 meters

apart. It is either a functionless relic from earlier construction

versions (from Stonehenge 3 I) or a function in the sense of a pure

symbol.

The big horseshoe embraces the small one. It consisted of ten

sandstone blocks (so-called sarsen), which were connected in pairs by a

third on their upper side. Over 5 m high, they weigh up to 50 tons and

must have been moved on sleds pulled by an estimated 250 men, on

inclines of up to 1000 men. Alternatively, the use of draft animals is

discussed.

The mighty sarsen horseshoe is followed by the circle of

originally 60 bluestones. They are, on average, a fair bit smaller than

those of the bluestone horseshoe and are tapered (not cylindrical) in

shape.

The formation of this bluestone circle is surrounded by

another circle, which in turn was constructed from sarsen: originally 30

in number, approx. 4.5 m high and connected to one another by 30 blocks

placed on top, so that a closed ring structure was created.

The

sacrificial stone, whose name is also misleading because it is easily

confused with the altar stone, is currently located in the middle of the

north-eastern opening of the ring wall, at the exit of the complex, so

to speak. The audio guide that takes visitors around the monument notes

that this stone was probably standing upright, and that its red spots

are not blood (which would have long since weathered and washed away)

but inclusions of iron oxide . The naming "victim stone" is therefore

more than questionable.

The Heelsstone or Friars Heel, in German as

"heel stone", is relatively far outside the ring wall.

The four

station stones.

Other special features:

The Aubrey Holes (56

pieces)

The Y and Z holes (29 and 30 pieces)

Laser scans of the

surfaces of all surviving 83 monumental stones at Stonehenge were made

on behalf of English Heritage. A total of 72 previously unknown

engravings were discovered. 71 of them show axes (up to 46 cm tall), one

a dagger. The site resembles the stone circles of northern Scotland

known as the Ring of Brodgar.

In 1995, the excavation findings from the 20th century were evaluated

and divided into three phases based on 14C dating. A slight change made

in 2000 to an older dating is based on the meanwhile improved method

(Bayesian statistics) of evaluating the 14C data. By 2009, other minor

modifications were added.

Based on their own evaluations,

employees of the most recent data collection presented a new study at

the end of 2012, in which they proposed five phases instead of the

previous three – also using a Bayes classifier. A similar interpretation

had already been attempted in 1979 but received little attention.

stonehenge 1

The first building was about 115 m in diameter and

consisted of a circular rampart with a ditch surrounding it (7 and 8),

according to the classification an atypical henge complex. Opposite the

large north-east opening of this ring wall was a smaller one to the

south (14); Bones of deer and ox were placed at the bottom of the ditch.

These bones were much older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch

and were well preserved when buried. The start of the first phase is

estimated at approx. 3100-2900 cal v. dated. At the outer inboard edge

of the area thus bounded was a circle of 56 holes (13), named the Aubrey

Holes after their discoverer, John Aubrey.

A second rampart (9)

now surrounding the outer ditch could also come from this phase

(Stonehenge 1), which can be defined as pre-megalithic.

stonehenge 2

Visible remains that could safely indicate the

appearance of building structures during the second phase no longer

exist. The dating was therefore rather indirect, including finds from

"grooved ware" (English Grooved Ware), which belong to this period (late

Neolithic). Shapes of holes detectable in the ground could be found in

the early third millennium BC. to have been created and to have carried

posts. Other posts may thus have stood in holes discovered at the north

entrance; two parallel rows of posts would have run inwards from the

south entrance. However, at least 25 of the Aubrey Holes contained

cremation remains dating from about two centuries after the holes were

dug. The holes were therefore in use as burial sites - they may have

been converted for this purpose, or the hypothetical posts were removed

at each burial. The remains of thirty other cremations were discovered

in the ditch and at other points on the site, mostly in the eastern

half. Unburned pieces of human bones from this period were also found in

the ditch.

Stonehenge 3 I

In the center of the sanctuary,

around 2600-2400 B.C. Two concentric semicircles of 80 stones, the

so-called bluestones, were laid out. Although they were later moved, the

holes in which the stones were originally anchored (the so-called Q and

R holes) remain detectable. Again, there is little dating evidence for

this phase. As mentioned, the bluestones come from the area of the

Preseli Mountains, which are about 240 km from Stonehenge in what is now

Pembrokeshire in Wales. The stones are mostly dolerite interspersed with

some inclusions of rhyolite, tuff and volcanic ash. They weigh about

four tons. Known as the Altar Stone (1), the six-ton stone is the only

one made of green sandstone. It is twice the size of the largest of the

stones from the bluestone horseshoe (which does not yet exist at this

stage) and is also from Wales. It may have stood upright in the center

as a large monolith, perhaps it was intended to lie flat. Many of the

early megalithic complexes represent burial facilities: the giant tombs,

also known as devil's beds.

At that time, the entrance was

widened so that its two side parts now pointed exactly to the positions

of the sunrise at the summer and winter solstices at that time. As

mentioned, the blue stones were removed after a while and the remaining

holes (Q; R) were filled.

The Heelstone (5) may also have been

placed outside the north-east entrance during this period. However, the

dating is uncertain, in principle every section of the third phase is

possible. Furthermore, pressure accumulations in the immediate area of

the entrance are sometimes interpreted in such a way that up to three

menhirs could have stood side by side here, but such traces also result

from the repeated change in the position of a single menhir. In any

case, the fact is that there is only one in the entrance area today. It

is 4.9 m long, probably fell down a long time ago and is called a

sacrificial stone (4).

Also included in phase 3 is the erection

of the four station stones (6) and the construction of the avenue (10),

a path bordered on both sides by a ditch and a mound of earth, also

known as the Processional Way, which leads to the River Avon over a

distance of 3 km. Investigations of this route showed that it ran

through a meltwater channel from the last ice age, which was only

slightly reworked.

At some point in the third construction phase,

trenches were dug both around the two station stones of the north-south

diagonal and around the heelstone, which must have stood as a single

monolith at least since then. This phase of Stonehenge's construction is

that which the archer of Amesbury may have seen; towards the end of the

phase, Stonehenge appears to have replaced Avebury's henge as the

region's central cult site.

Stonehenge 3 II

At the end of the

third millennium BC, between about 2550 and 2100 BC according to

radiocarbon dates. BC, the main building activity took place. Now the

two sarsen constructions (grey in the plan) were erected, which

determine the overall impression of Stonehenge today. Many of these 74

megaliths, the smaller around 25, the larger around 50 tons, come from a

quarry near Marlborough 30 km to the north, as geochemical tests in 2020

showed.

30 of these blocks formed a circle with a diameter of

thirty meters. The fact that there were once 30, grouped into a complete

circle, could only be proven in 2013, when a long-lasting drought caused

differences in the vegetation to show the compaction in the subsoil,

even where the stones themselves are no longer there. The horseshoe from

the 5 triliths was then set up within this circle.

The surfaces

of all sarsen are hewn and have been smoothed. The capstones of the

sarsen formations (circle + horseshoe) have two holes worked into their

underside, which combine with the pegs at the top of the supporting

stones to form a version of the tongue and groove connection. A symbolic

purpose of this measure cannot perhaps be ruled out, but it certainly

served to wedge the elements together. A similar pattern is found on the

end faces to the left and right of each of the 30 capstones of the

circle, and they were also given the shape of carefully crafted segments

of a circle to connect them to form a perfect ring.

Furthermore,

some of the sarsen have carved or scratched images. Perhaps the oldest,

a flat rectangular figure at the top of the inside of the fourth

trilith, may represent a mother goddess. Perhaps closer than this

interpretation would be to think of an abstract representation of the 4

station stones opposite this symbol - but here too it is still unclear

what their meaning is. As for the other symbols, fewer questions remain.

Worth mentioning in particular on stone 53 is the depiction of a bronze

dagger and fourteen ax heads, further depictions of ax heads can be

found on stones 3, 4 and 5. It is difficult to date the depictions, but

there are similarities to Late Bronze Age weapons. On the other hand, it

is not easy to decide whether these depictions were attached to the

megaliths that were still in the process of being made, or later,

possibly on working platforms erected for this purpose.

Stonehenge 3 III

At a later point in the Bronze Age, the bluestones

appear to have been raised again for the first time. However, the exact

appearance of the site in this period is not yet clear.

Stonehenge 3 IV

At this stage, roughly between 2280 and 1930 B.C.,

the bluestones were rearranged again. One part of them was placed as a

circle between the sarsen circle and the sarsen horseshoe, and the other

part was placed in the form of an oval around the center of the

monument. Some archaeologists believe that an additional batch of

bluestone had to be brought in from Wales to make this new building

project possible. The altar stone may have been slightly relocated

parallel to the construction of the oval, possibly away from the center

to its present position (closer to the base of, among other things, the

sarsen horseshoe). The work on the bluestones of this phase (3 IV) was

carried out rather carelessly compared to the work on the sarsen in the

previous phases. The bluestones, which were initially removed and then

set up again, were poorly embedded in the ground, and some of them soon

fell over again.

Stonehenge 3 V

Soon after, the north-east

half of the bluestone oval constructed in Phase 3 IV was removed,

creating the arcuate formation we know today as the bluestone horseshoe.

This structure mirrored that of the Sarsen Horseshoe, except that it was

constructed from discrete and significantly smaller, but nearly double

the number of stones: 19 to the 10 supporting stones of the Sarsen

Horseshoe. This reorganization of the monument is dated from 2270 to

1930 BC. dated. This phase (Stonehenge 3 V) thus runs parallel to that

of Seahenge in Norfolk.

Stonehenge 3 VI

Around 1630/1520 BC

B.C., two further rings of pits were drilled just outside the Sarsen

circle, in addition to the circle of Aubrey pits found opposite on the

inland periphery of the ring wall. The new circles are called the Y and

Z holes (11 and 12). Their 30 and 29 holes, respectively, were never

occupied by stones, otherwise soil compaction could have been detected

in them due to the pressure exerted by the stones. The Stonehenge

monument appears to date from around 1600 to 1400 BC. to have been

abandoned, possibly in connection with the decline or displacement of

the culture of its creators by a subsequent one. The holes filled up

over the next few centuries, the top layers of this material date from

the Iron Age.

The orientation was such that on the morning of Midsummer's Day, when

the sun rises furthest to the north-east in its course of the year, it

rises directly over the Heelstone and sends its rays in the direction of

the structure. The meaning of the long shadow at the moment of sunrise

that the Heelstone cast on this occasion, among other things, on the

altar stone, the base of the bluestones and the sarsen horseshoe, could

have had, is not known.

However, it is taken for granted that

this architecture was, on the whole, consciously conceived and realized.

The point at which the sun rises on the date of summer solstice is

directly related to latitude. In order to implement the orientation of

the monument according to a plan that provides for this, it must have

been calculated or practically determined according to its relative

position (51° 11′). This approach should therefore have been fundamental

to the placement of the stones in at least some of the phases of

Stonehenge. The heelstone and with it the symmetry axis of the horseshoe

are therefore interpreted as components of a solar corridor that

includes the rise of our day star.

Among other things, Stonehenge

may have been used to predict the summer and winter solstices and the

vernal and autumnal equinoxes, seasonal turning points important to an

agricultural culture.

According to an earlier research finding,

the moon's course would play a far greater role than previously assumed.

In 1963, Gerald Hawkins described in the article Stonehenge Decoded in

the journal Nature that the 19 megaliths of the bluestone horseshoe can

be used to calculate the so-called Meton cycle - an approximately

19-year period after which the summer solstice and lunar eclipse occur

on the same day fall. Since the latter event always includes the full

moon and this leads to particularly violent tidal currents, a

correspondingly strong low tide can be expected in the Avon at noon.

The Neolithic circle of Stonehenge, which begins with the 1st phase

around 3100/2900 cal B.C. B.C., has construction features and

characteristics with the Aubrey holes on the outer edge which, according

to the computer scientist Friedel Herten and the geologist Georg

Waldmann, indicate a lunisolar calendar. Their 2018 study suggests that

the lunisolar calendars of Stonehenge and the Nebra Sky Disc were based

on an 18.6-year cycle and relied solely on observing the movement of the

northern lunar swells. With both systems, solar and lunar eclipses could

have been predicted to the day more than 5000 years ago.

Roger

Mercer has claimed that the bluestones are exceptionally finely worked.

He postulated that they were once brought to Stonehenge from an as yet

unidentified older monument in Pembrokeshire. It is true that most other

archaeologists agree that the bluestones were worked with no less care

than the sarsen stones. However, if Mercer's reasoning were correct, the

bluestones could have been transported from that location in order to

reinforce a newly established alliance with the two sarsen formations

through their composition. On the other hand, the interpretation that

the Bluestone structures symbolize an inferior, and therefore 'small'

enemy in this alliance would not speak against it either: The Bluestones

are, as I said, relatively tiny, downright dwarfs compared to the giants

of the Sarsen. Likewise, the change to the order proposed by Mercer in

the sense of the dating outlined above (according to which the

Bluestones were first in the Stonehenge area, then apparently

temporarily displaced 'by the Sarsen') would not fundamentally change

the political character of his thesis.

Complementing this

approach, some archaeologists have suggested an interpretation that

suggests that the very hard igneous material of the bluestones and the

relative softness of the blocks of sarsen made of sedimentary sandstone

could be symbolic of an alliance between two cultures or groups of

people originating from each other areas and therefore must have had

different backgrounds.

New analysis of contemporary burial sites

nearby, known as the Boscombe Bowmen, has shown that at least some of

the people who lived at the time of Stonehenge 3 may have come from what

is now Wales. Also, an analysis of the crystal polarization in the

bluestones revealed that they could only have come from the Preseli

Mountains.

Bluestone outcrops resembling the Stonehenge 3 IV

small horseshoe have also been found at the sites known as Bedd Arthur

in the Preseli Hills and on the island of Skomer off the south-west

Pembrokeshire coast.

Aubrey Burl claims that the bluestones were transported from Wales

not solely by humans, but at least part of the way by Pleistocene

glaciers. However, no geological evidence of such transport between the

Preseli Mountains and Salisbury Plain has been found. Furthermore, no

other specimens of this unusual dolerite stone have been found near

Stonehenge.

There is much speculation about the method of

construction of the facility. If the bluestones didn't change places by

glacial shipment, as Aubrey Burl suspects, but were transported by human

hands, there are many methods of moving giant stones with ropes and

wood.

As part of an experiment in 2001, an attempt was made to

transport a larger stone along the assumed land and sea route from Wales

to Stonehenge. Numerous volunteers pulled him overland on a wooden sled

and then loaded him onto a replica of a historic boat. However, this

soon sank together with the stone in rough seas in the Bristol Channel.

A second experiment in August 2012, however, was successful and brought

a bluestone by sea via the Bristol Channel and the Avon using Stone Age

methods. Archaeological experiments in 2016 showed that land transport

with sleds on a route made of halved tree trunks was also possible with

remarkably little effort.

It has been suggested that A-shaped

wooden frames, similar to a roof construction, were used to erect the

stones and move them into a vertical position with ropes. For example,

the capstones could have been gradually raised with wooden platforms and

then slid into place at height. Alternatively, they could have been

pushed or pulled into position up a ramp. The carpenter's tenon joints

on the stones suggest that the builders already had woodworking skills.

Corresponding knowledge should have been a great help in the conception

and construction of this monument.

It has been suggested by

Alexander Thom that the builders of Stonehenge used the megalithic yard

as the basis for the various lengths.

The depictions of weapons

engraved on the sarsen stones are unique in megalithic art in the

British Isles. Elsewhere, abstract images were preferred. The horseshoe

arrangement of the stones is similarly unusual for this culture, as

elsewhere the stones were always arranged in circles. However, the ax

motif found is comparable to the symbols in Brittany at this time. It is

thus likely that at least two construction phases of Stonehenge were

constructed under significant continental influence. This would explain,

among other things, the atypical structure of the monument.

There

are estimates of the manpower required to construct each phase of

Stonehenge. The sums exceed several million man-hours. Stonehenge 1 is

believed to have required around 11,000 hours of work, Stonehenge 2

around 360,000, and the various parts of Stonehenge 3 may have required

up to 1.75 million hours of work. The processing of the stones is

estimated at about 20 million working hours, especially considering the

moderately efficient tools at that time. The general will to erect and

maintain this building must therefore have been extremely strong and

required a strong social organization. In addition to the extremely

complex organization of the construction project (planning, transport,

processing and precise installation of the stones), this also requires

years of overproduction of food to feed the actual "workers" while they

work for the project.

First written mentions

The entire period from the archaeologically

proven abandonment of Stonehenge at the end of the Bronze Age to the

conquest of England by the Normans is historically obscure. Henry of

Huntingdon was first mentioned by name in his History of England around

1130. Geoffrey of Monmouth addresses the stone circle in more detail in

his History of the Kings of Britain, written around 1135. He attributes

the construction of the monument to the magician Merlin.

The

historian Polydor Virgil (1470-1555) takes up Monmouth's description and

also explains Stonehenge as a monument that the magician Merlin erected

with the help of his magical powers at the time of the conquest of

England by the Anglo-Saxons.

Theory since the early modern period

Around 1580, antiquarian William Lambarde ruled out a supernatural

origin of the complex for the first time by observing that carpentry

techniques were transferred to Stonehenge's stone construction when the

stone circle was built. He is also the first to recognize that the

stones were not brought from Ireland by magic, as Merlin previously

described, but that they come from the Marlborough region.

The

first book about Stonehenge appears in 1652. Its author, the master

builder Inigo Jones, who extensively examined the complex on behalf of

the English king James I, explains the stone circle as a Roman temple in

honor of the god Coelus. In the years that followed, various other

authors tried to interpret the stone circle: In 1663, the doctor Walter

Charleton assumed that Stonehenge was a coronation site for the Danish

kings of England. The historian Aylett Sammes credits the ancient

Phoenicians with the construction of the complex in 1676.

At the

end of the 17th century, the archaeologist John Aubrey (1626–1697)

recognized the connection between Stonehenge and comparable monuments in

Scotland and Wales and was the first to assign the construction of all

these complexes to local builders. The fact that Aubrey attributes

Stonehenge and all similar monuments in the British Isles to the Celts

proves to be fatal for future research and the interpretation of the

complex up to our time. His error becomes understandable from the

scientific perspective at the end of the 17th century: There is no way

of dating prehistoric archaeological monuments; the age of the world is

still dated to a few thousand years after the biblical story of

creation, and the literature of ancient writers known to Aubrey contains

no evidence of a pre-Celtic population of the British Isles. However,

Aubrey can glean detailed descriptions of the druids as a Celtic class

of priests from ancient Latin and Greek authors, and so he cautiously

assumes that the stone circles are the temple complexes of these druids.

In fact, there are more than 1,000 years between the abandonment of the

complex at the end of the Bronze Age and the first appearance of

so-called Celtic cultural features in Europe.

Researchers of the

18th century enthusiastically took up Aubrey's thesis: in his Critical

History of Celtic Religion and Learning, written in 1719, the historian

John Toland assigned Stonehenge to the Druids. In the years 1721 to

1724, the doctor William Stukeley carried out the most detailed and

precise measurements of the system up to that point and was the first to

suspect that the system was axially aligned with the point of the summer

solstice. In 1740 he summarized his results in a book and, using

questionable and unscientific methods, also interpreted Stonehenge as a

Druidic temple.

In his book The Geology of Scripture, Henry

Browne, curator of Stonehenge since 1824, interprets the stone circle as

an antediluvian temple from the time of Noah. He refers to the theories

of the paleontologist William Buckland (1784-1856), who represents the

theory of catastrophes or cataclysms instead of the theory of evolution.

First astronomical theories

At the beginning of the 20th century,

the astronomer Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836–1920) was the first to open

up a possible astronomical use of the facility. Like Stuckeley a century

before him, he suspects that the complex is aligned with the point of

the summer solstice, but speculates further on the use of the stone

circle as an astronomical calendar for determining sacred Celtic

festivals. Lockyer's theory was ignored by the archaeologists of his

time, since his calculation bases were imprecise and he selected them

arbitrarily in order to get the results he wanted. Stonehenge is

therefore still considered "only" as a prehistoric cult or sanctuary by

archaeological experts.

Astronomer Gerald Hawkins attempted to

change this picture when he published his book Stonehenge Decoded in

1965. With the help of detailed measurements of the monument and

complicated calculations, Hawkins wants to prove that Stonehenge served

as a kind of Stone Age computer with which its builders would have been

able to predict lunar eclipses quite reliably, for example. Like John

Aubrey's "Celtic Thesis" at the time, Hawkins' theory is now being

enthusiastically received by the general public. Experts, on the other

hand, tear his research apart: The archaeologist Richard J. C. Atkinson,

for example, proves that Hawkins also included parts of the system in

his evidence that demonstrably existed or were built at different times

and therefore cannot be part of the same system.

Modern exploration of Stonehenge begins with the explorer William

Cunnington (1754–1810). Cunnington's excavations and observations

confirm Stonehenge's pre-Roman dating. His research is published in the

years 1812-1819 in the local historical work Ancient History of

Wiltshire by historian Richard Colt Hoare. From 1880, William

Flinders-Petrie oversaw the first modern restoration. The numbering of

the stones, which is still in use today, also goes back to him. Stone 22

fell during a heavy storm night on December 31, 1900.

Around

1900, John Lubbock, based on bronze objects found in neighboring burial

mounds, shows that Stonehenge was already being used in the Bronze Age.

William Gowland (1842–1922) restored parts of the site and undertook the

most painstaking excavation to date, which was completed in 1901. From

his finds he concludes that at least parts of the monument were created

at the time of the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.

Archaeologist William Hawley excavated about half of the site in

1919-1926. However, his methods and reports are so inadequate that no

new insights are gained. During this time, however, the geologist H.

Thomas succeeded in proving that the bluestones were brought from South

Wales by the builders of the plant.

In 1950 the Society of

Antiquaries commissioned archaeologists Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott

and John Stone to carry out further excavations. You will find many

fireplaces and develop the classification of the individual construction

phases, as it is still the most common today.

Archaeologists

Richard Atkinson and Stuart Piggott continued to excavate in the second

half of the 20th century. With the development and perfection of

radiocarbon dating from the middle of the 20th century, it is now

possible for the first time to reliably date the complex to the first

half of the 2nd millennium BC. Atkinson and Piggott are also restoring

other parts of the complex by re-erecting some of the fallen and crooked

stones and cementing them in the ground. These reconstructions are still

limited to stones that have been proven to have only fallen in modern

times or that have or have become crooked.

Much of the recent

damage to the monument is due on the one hand to the earlier need for

stones by the surrounding population and on the other hand to the

souvenir needs of earlier visitors. Meanwhile, a blacksmith from nearby

Amesbury offered tourists a hammer to borrow, so they could chip pieces

off the stones as souvenirs.

Since September 2006, archaeologists

have been excavating the remains of a Neolithic village dating to

2600-2500 BC (Grooved Ware) at Durrington Walls, 2 miles from

Stonehenge, as part of the Stonehenge Riverside Project. "We think we've

found the village of Stonehenge's builders," said Mike Parker Pearson,

the excavation project manager at the University of Leeds in January

2007.

From March 31 to April 11, 2008, the first excavation in

the stone circle since 1964 will take place. Led by Timothy Darvill and

Geoff Wainwright, a trench dug by Hawley and Newall's excavations in the

1920s is being reopened to search for organic material. With the help of

mass spectrometry and radiocarbon dating, it is thus possible to

determine the point in time at which the bluestones were erected with an

accuracy of a few decades.

In 2010, remarkable new discoveries

are being made at the site. The application of modern technology

indicates that there is much more to Stonehenge than just the

world-famous circle of stone giants. The entire area, which covers many

square kilometers, seems to be criss-crossed by places of worship and

mysterious complexes. British researchers like Vincent Gaffney from the

University of Birmingham believe that we only know ten percent of what

Stonehenge really was and what it looked like in detail. A scientific

survey of the site that has just begun has already uncovered new circles

- 'Timberhenge' -, ditches and mounds, as well as carefully constructed

ramparts and depressions.

Investigations in 2013 on the avenue

leading from the River Avon in a southwesterly direction into the

complex show that a meltwater channel has been running here since the

end of the Ice Age. Michael Parker Pearson of the University of

Sheffield and Heather Sebire of English Heritage assume that

Stonehenge's builders realized that the gully runs exactly in the

direction of the winter solstice. So they explain the location of the

prehistoric complex with this found terrain feature.

In September

2014, Vincent Gaffney from the University of Birmingham announced at the

British Science Festival in Birmingham that, based on the data collected

in recent years as part of the international Stonehenge Hidden

Landscapes Project (areal investigations using ground radar and

magnetometers have been ongoing since 2010). on an area of 12 km² a

first three-dimensional map with the traces of the as yet unexcavated

finds in the ground has been drawn up. This includes 17 previously

unknown wooden and stone structures as well as dozens of newly

discovered burial mounds. It is now believed that Stonehenge was the

center of scattered ritual monuments that gradually expanded over time.

In November 2015, the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological

Prospection and Virtual Archeology (Vienna) reported the discovery of a

12-14 °C warm spring 3 km away near Amesbury, which, because it does not

freeze over, is beneficial for animals and thus for could have been a

hunter. Bones with stone arrowheads embedded in them have been found,

and nodules of flint in an area of a spring pond.

The Stonehenge complex was fenced off in 1901 and since then has only

been accessible for an entrance fee. During the First World War, a field

airfield (Stonehenge Aerodrome) was laid out to the west near the

facility. After the war it was used as a depot for building materials

and later as a pig farm.

More recently, Stonehenge has been

influenced by the close proximity of two busy roads: the A303 between

Amesbury and Winterbourne Stoke, which was upgraded to a motorway in

1958, and the A344, which passes directly by the monument. There have

been various proposals to relocate or tunnel the roads.

The flow

of visitors increased massively after the Second World War. Car parks

and toilets have been created opposite the stone circles on the other

side of the A344. After repeated vandalism, the facility was guarded

around the clock. A hut was built for the wardens next to the parking

lots.

Since 1968 a tunnel under the A344 linked car parks and the

monument; a semi-underground building with a café and museum shop was

built in it and expanded several times. For decades, the situation was

perceived as a national disgrace. Additional fences were erected in

1978; Since then, visitors could no longer move freely between the

stones, but had to stay on a path between the wall and the stone

circles. Because of the incessant tourist rush, only the

circumnavigation of the facility remained in the stream of visitors. In

2005, 800,000 visitors came. It was hardly possible to linger for

reflection in the memorable place.

Redesign since 2013

Since

December 2013, Stonehenge's surroundings and visitor access have been

rearranged. The A344 road was abandoned in the section of the facility,

and the parking lots and the old visitor care facilities were demolished

and renatured by mid-2014.

Instead, a visitor center with

exhibitions and other offers was built about two kilometers from the

stone circles. The buildings cannot be seen from the monument, providing

a much more private experience than before. Visitors can walk to the

stone circles from the museum via a processional way or take a shuttle

bus. The time on the road can and should be used to get in the mood with

the help of an audio guide in many languages. The use of the shuttle bus

and the audio guide are included in the entrance fee. English Heritage

members (including temporary members) receive free access. Advance

reservations are recommended to visit the facilities.

An

exhibition about the builders of Stonehenge, their culture and their

history will be shown for the first time in the visitor center. It

consists of a central video and five thematic information stations. The

video shows the construction of the plant and the resulting changing

landscape. The stations provide information on three levels. The

exhibition is designed along with the audio commentary and information

boards on the site; all three media work together and complement each

other. Outside the visitor center are reconstructed huts and pits of

Stonehenge's builders.

The route from the visitor center to the

monument follows the former road; about halfway you can see the plant

for the first time from a small hilltop. The shuttles stop there briefly

and visitors have the choice of walking the rest of the almost one

kilometer walk in order to approach the stone circles independently, or

covering the rest by bus.

The new buildings were erected without

foundations so as not to disturb any archaeological finds found in the

ground below.

After the Renaissance, with the rediscovery and spread of classical

literature, there was increasing interest in the druids mentioned in the

ancient texts. Since the scientific exploration of prehistory was still

in its infancy, Stonehenge was assigned to the Druids as a pre-Roman

temple. This erroneous association is still influential. In 1781, the

Englishman Henry Hurle founded a secret society called the Ancient Order

of Druids. Although interest in druids waned in the mid-19th century,

the religious orders that arose persisted. Her trips to Stonehenge

always attracted onlookers. A striking example is the ceremony of the

Ancient Order of Druids in August 1905, when 700 members of that order

gathered at Stonehenge and solemnly received 256 candidates into their

order. Today, modern-day druids form part of the neo-religious

landscape, specifically neo-paganism. They meet regularly at Stonehenge

and hold their ceremonies there.

On the summer solstice of 1972,

Stonehenge hosted one of the free festivals popular in Britain at the

time for the first time. This Stonehenge Free Festival has grown in

popularity over the years; In 1984, an estimated 70,000 visitors met at

the stone circle and celebrated the solstice with live music and various

Druidic and neo-pagan cults. In 1985, in the run-up to the festival,

there were violent conflicts between visitors and the police (battle of

the beanfield), whereupon the regulatory authorities prohibited the

festival in Stonehenge and closed the site to all visitors, especially

on the two solstices and the equinoxes.

In 1998, small groups of

neo-pagans (including Druids) were allowed back into the stone circle,

and at the turn of the millennium the Secular Order of Druids, invoking

freedom of religion, obtained the Stonehenge ban on assembly lifted. In

2014, 36,000 people, both tourists and devout druids, celebrated the

beginning of the longest day of the year at Stonehenge on the night

before. The police arrested 25 people – mostly for drug-related

offences.

In the 1920s, amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins (1855–1935) put

forward a theory according to which the prehistoric megalithic

structures – including Stonehenge – were connected to one another by

so-called ley lines, dead straight lines. However, Watkins thought of

real path connections. The author John Michell (b. 1933) took up this

thesis; In his 1969 book The View over Atlantis, he no longer

interpreted the lines as paths, but associated the ley lines with

geomagnetic force fields and "power centers".

In the years that

followed, this view found numerous followers among the followers of

esotericism up to the present day. So Michell's thesis should be proof

that the prehistoric builders of Stonehenge and comparable megalithic

monuments still lived in complete harmony with the cosmos and could

sense such "lines of force" and "centres" on which they then built

temples like Stonehenge, for example.

In 2010, documentary

filmmaker Ronald P. Vaughan claimed to have discovered a remarkable unit

of measurement during his research. At 27,830 meters, the distance to

the center of the neighboring stone circle of Avebury corresponds

exactly to the 1440th part of the equator's circumference (1:1440 ≙ 1

minute : 1 day).

The heel stone was also once known as Friar's Heel. A legend that can

be dated back to the 17th century at the earliest tells the origin of

the name:

“The devil bought the stones from a woman in Ireland and

brought them to Salisbury Plain. One of the stones fell into the Avon,

he deposited the rest on the plain. The devil cried out loudly, 'No one

will ever find out how these stones got here.' A monk replied, 'Only you

believe that!' whereupon the devil threw one of the stones at him,

hitting his heel with it. The stone got stuck in the ground and that’s

how it got its name.”

Some believe that the name Friar's Heel

derives from Freya's He-ol or Freya Sul, named after the Germanic deity

Freya and the (supposedly) Welsh words for 'way' and 'Sunday'

respectively.

Stonehenge is often associated with Arthurian

legends. Geoffrey of Monmouth claims that Merlin brought Stonehenges

from Ireland, where it was originally built on Mount Killaraus by giants

who brought the stones from Africa. After his rebuilding at Amesbury,

Geoffrey goes on to describe first Ambrosius Aurelianus, then Uther

Pendragon and later Constantine III. buried inside the ring. In many

places in his Historia Regum Britanniae, Geoffrey mixes British legend

with his own imagination. He associates Ambrosius Aurelianus with the

prehistoric monument simply because its name resembles that of nearby

Amesbury.

In modern times, pseudoscientists such as Erich von

Däniken have suggested that Stonehenge was built by extraterrestrial

visitors to Earth.

The first literary works related to Stonehenge were written at the

end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century: During this time

Edmund Spenser wrote his epic poem The Faerie Queene and Thomas Rowley

wrote his drama The Birth of Merlin. Both works deal with the connection

between the wizard Merlin and Stonehenge and are largely inspired by

Geoffrey von Monmouth's book History of the Kings of Britain. The poet

John Dryden wrote a poem in the second half of the 17th century in which

he pays homage to Stonehenge as the coronation site of Danish kings. In

the 18th and 19th centuries, however, Stonehenge hardly played a role in

non-scientific literature.

The novel Tess von den d'Urbervilles

by Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), published in 1891, is worth mentioning

again. Stonehenge plays a central, symbolic role in this love story. The

novel was filmed in 1979 by Roman Polański with Nastassja Kinski in a

leading role and later won three Oscars; it was not filmed on location.

The non-scientific literature about Stonehenge in the 20th century

is considerably richer and is mainly dominated by historical novels.

From the now almost unmanageable number of publications, mention should

be made of, for example, the 1985 novel Pillar of the Sky by Cecelia

Holland, the 1995 novel Die Druiden von Stonehenge by Wolfgang Hohlbein

or the 2001 German novel Stonehenge by Bernard Cornwell. But also family

sagas, horror, fantasy and even crime novels take up Stonehenge as a

more or less dominant part of their plot. John Cowper Powys combines

legends of the Holy Grail and the Arthurian myth in one episode with

Stonehenge in his monumental work on life in the 1920s Glastonbury

Romance.

Only three images of Stonehenge are known from the entire Middle

Ages. The first pictorial representations of the complex come from

manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries. Relatively realistic

pictorial representations have existed since the 16th century.

The first of the three illustrations shows the system in a panoramic

view - perspectively, however, distorted into a rectangle; the second

illustrates the construction of the complex by the magician Merlin and

shows how he lifts one of the capstones onto two supporting stones. The

third figure was rediscovered in 2007 and comes from the historical work

Compilatio de Gestis, which was probably written down around 1441. The

text accompanying this illustration also refers to the construction of

the complex by the magician Merlin.

The Dutch artist Lucas de

Heere (1534–1584) carried out the first realistic depiction as a

watercolor to illustrate his 1573–1575 handwritten report Corte

Beschryving van England, Scotland endeireire. The picture shows the

stone circle from an elevated position from a northwesterly direction.

The human figure in the center of the picture leans against supporting

stone number 60. An engraving from 1575, signed only with the initials

'R.F.', and a watercolor from 1588 by William Smith in the manuscript

Particular Description of England show the plant from a view similar to

that of de Heere's watercolour. All three pictures are probably based on

the same, unknown template. The engraving, signed only “R.F.”, was the

model for an illustration of Stonehenge in the antiquities book

Britannia by William Canden (1551–1623) in 1600. The illustration was in

turn a model for other images of Stonehenge.

The writings of

antiquarian John Aubrey (1626–1697) in the late 17th century, the

research on Stonehenge published in 1740 by physician William Stukeley,

and the poems of Ossian by James Macpherson (1736–1796) influenced

artists throughout the 18th century , to interpret Stonehenge in their

pictures as a Celtic or Druidic place of worship.

In 1797 the

tallest of the still standing triliths inside the complex fell down. The

problem for the artists was how to reproduce the structure and depth of

the setting of the stones in their pictures. As a reaction to this,

pictures from the 18th and 19th centuries now show the stone circle

preferably from a particularly low perspective and depict the stones

against the backdrop of a low-lying horizon. One of the most famous

images adopting this perspective is a watercolor by John Constable

(1776–1837), who visited Stonehenge in 1820. Constable first made only a

sketch and then 15 years later created a watercolor of the stone circle.

Other well-known images of Stonehenge come from the English landscape

painter William Turner (1775–1851). Around 1811 he drew a first view of

the stone circle, which he later used as a template for a painting.

Another picture was taken in 1828 and shows Stonehenge during a

thunderstorm.

In the 1970s, the painter and sculptor Henry Moore

(1898–1986) created the 16-lithograph Stonehenge Album[45], one of the

most important recent works of art on Stonehenge.

In his work Broken Circle for sextet, the German composer Valentin

Ruckebier makes several references to Stonehenge and the numerous

theories and legends surrounding the stone circle's ancient purpose.

Hungarian progressive metal band Stonehenge is named after the monument.

From 1972 to 1984, the Stonehenge Free Festival music festival was held

annually between the stones of Stonehenge, which was very popular with

bands and audiences.

Chris Evans and David Hanselmann released the

concept album Stonehenge in 1980, in which they linked various myths,

including the Arthurian legend.

In the 2013 music video Stonehenge,

the Norwegian comedy duo Ylvis asked about the purpose of the building.

Replicas and Derived Names

America's Stonehenge is an unusual

stone circle formation near Salem, New Hampshire in the northeastern

United States.

Maryhill Stonehenge, a true-to-scale copy of

Stonehenge in the reconstructed original state, was built by Sam Hill as

a war memorial near Maryhill in Washington State. It is also aligned

with the rising point of the midsummer sunrise. This was done using a

virtual horizon instead of the sun's position on the actual landscape

horizon as seen today.

Stonehenge inspired geologist Jim Reinders to

write his work Carhenge (1987) or "Auto-henge" at Alliance, Nebraska. He

and his family built the replica out of gray-painted cars and dedicated

it to his late father.

In New Zealand, Stonehenge Aotearoa, a

functional replica dedicated in February 2005, is used as a teaching

tool for astronomical contexts and Maori culture.

Metalhenge was

inaugurated in 2021 on the disused part of the block landfill site in

Bremen. The name is explicitly based on Stonehenge, the "stone" in the

designation was replaced by "metal" due to the rusted harbor sheet

piling as a building material.

The Muchołapka, a 10-meter-high,

30-meter-diameter, dodecagonal concrete ring erected during World War II

in Ludwikowice Kłodzkie, Poland, is also known as "Hitler's Stonehenge".