Location: Ricketts Ave and US 24, Bartonville, IL Map

Constructed: 1895-1910

The Peoria State Hospital, also known as Bartonville State Hospital or the Illinois Asylum for the Incurable Insane, was a psychiatric hospital in Bartonville, Illinois, near Peoria, operating from 1902 to 1973. Its history reflects both progressive mental health reforms and the challenges of institutional care, set against a backdrop of architectural evolution, paranormal lore, and community efforts to preserve its legacy.

The Peoria State Hospital was established following the Illinois

General Assembly’s 1895 legislation to create the Illinois Asylum for

the Incurable Insane, aimed at relieving overcrowded county almshouses

where 2,985 “incurable” patients were held, often in deplorable

conditions. Governor John Altgeld appointed a three-person commission,

led by Peorian John Finely and including J.J. McAndrews (later a U.S.

Congressman), to select a site. Bartonville, near Peoria, was chosen,

and construction began in 1895.

The initial main building,

completed in 1897, was designed by architects Reeves and Baillie in the

Kirkbride Plan, resembling a feudal castle. However, it was never used

due to structural issues from abandoned mine shafts beneath, which

compromised its foundation. A 1927 hospital history offers an

alternative explanation, stating the castle-like design was “out of

harmony with modern ideas for the care of the insane” and was razed.

Under Dr. Frederick Howard Wines, the facility was rebuilt using a

cottage system, completed in 1902 under superintendent Dr. George A.

Zeller. This system prioritized smaller, community-like buildings over

large, imposing structures.

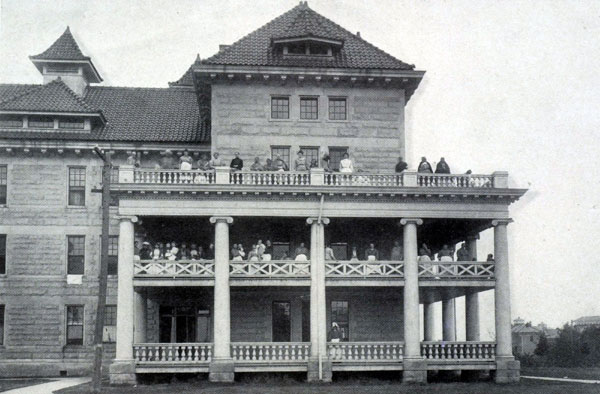

The Peoria State Hospital adopted a cottage plan, a progressive

departure from the monolithic Kirkbride asylums. By 1902, the campus

included 33 buildings, growing to 63 at its peak. These included:

Patient and caretaker housing: Small cottages fostered a

home-like environment.

Support facilities: A store, bakery,

kitchen, power station, and communal utility building made the

campus self-sufficient.

Specialized units: The Pollak

Tuberculosis Hospital, a nurses’ dorm, and a training school (opened

in 1906) were key components.

The campus was designed to be

parklike, with sprawling grounds and four cemeteries for

unidentified deceased patients, reflecting Dr. Zeller’s burial

system. The Bowen Building, a central administration and nurses’

dorm, was a prominent limestone structure until its demolition in

2017. The cottage system aligned with Zeller’s humane treatment

philosophy, emphasizing dignity and community over confinement.

The hospital opened on February 10, 1902, receiving 100 male

patients transferred from Jacksonville State Hospital. Initially

named the Illinois Asylum for the Incurable Insane, it was renamed

the Illinois General Hospital for the Insane (1907–1909) and then

Peoria State Hospital in 1909, reflecting its proximity to Peoria

and Zeller’s rejection of the “incurable” label.

Dr. George

A. Zeller, superintendent from 1902–1913 and 1921–1935, was a

pivotal figure. Influenced by the Peoria Women’s League, which

advocated for better mental health treatment, Zeller implemented

groundbreaking reforms:

Open-door policy: He removed bars

from windows and doors, eliminated restraints, and banned narcotics,

solitary confinement, and abusive practices like bloodletting or ice

baths.

Holistic therapies: Zeller introduced occupational

therapy, recreation, and work programs, believing mental illness

could be treated humanely.

Staff innovations: The hospital

adopted an eight-hour workday, placed women attendants on male

wards, and segregated patients with tuberculosis or epilepsy.

Public engagement: Zeller invited journalists and community members

to visit, fostering transparency and reducing stigma around mental

illness.

The hospital’s nursing program, established in 1906, was

ranked the nation’s best for 34 of its 36 years. By 1927, the

patient population reached 2,650, with 13,510 total admissions since

opening. At its peak in the 1950s, it housed 2,800 patients. The

hospital performed 94 lobotomies on severe cases but avoided abusive

experimental treatments, maintaining a high cure rate, though its

expense led to funding challenges.

Peoria State Hospital is renowned for its paranormal

stories, particularly the legend of A. Bookbinder, or “Old Book.” A

patient assigned to the burial crew, Old Book reportedly wept under a

“Graveyard Elm” at each interment. After his death, Dr. Zeller claimed

400 staff and patients witnessed Old Book’s ghost mourning at his own

funeral. Zeller documented this and other eerie experiences in his 1920s

book, Befriending the Bereft.

Other reported hauntings include:

Disembodied voices and a woman in white appearing in windows.

A

girl’s ghost in the Bowen Building basement, known for playing with

dolls.

Shadow figures and heavy boots heard in the Men’s Ward.

The

hospital’s paranormal reputation drew attention from Ghost Hunters

(2013, “Prescription for Fear”) and Ghost Asylum (2016), as well as

authors like Sylvia Shults, who wrote Fractured Spirits and Fractured

Souls about its hauntings. The four cemeteries, with over 4,000 burials

(many marked only by numbers), and notable graves like Rhoda Derry

(mistreated before arriving) and Emily Belsher (descendant of Sir

Frances Drake), add to the site’s mystique.

By 1972, the patient population had dropped to 600 due

to deinstitutionalization, budget cuts, and staffing shortages. The

Illinois government’s push to close long-term facilities, combined with

the hospital’s high operating costs, led to its closure in 1973. After

closing, the buildings were auctioned off. Developer Winsley Durand,

Jr., planned to convert them into office spaces, but his bankruptcy left

most structures vacant. Many of the 63 buildings were demolished,

leaving only 13 by 2025, including the Pollak Tuberculosis Hospital. The

Bowen Building was demolished in 2017, despite preservation efforts,

with its limestone blocks sold to recoup costs.

The Village of

Bartonville designated the site a Tax Increment Financing (TIF) district

to encourage redevelopment. Some remaining buildings now house

commercial and industrial businesses.

The Peoria State Hospital Museum, established in 2013

at 4208 W. Pfeiffer Road, Bartonville, is dedicated to preserving the

hospital’s history. Operated by the Mental Health Historic Preservation

Society of Central Illinois, it occupies three of the remaining

buildings and features artifacts like Dr. Zeller’s display case and the

last Peoria State Hospital Utica crib (a controversial restraint

device). The museum offers:

Historical tours: Guided tours of the

grounds, including the four cemeteries, with costumed actors and

slideshows.

Paranormal tours: Nighttime investigations of “hotspots”

using modern and historical equipment.

Events: Annual bazaars, car

shows, and Halloween attractions like the Old State Mine Haunted Trail,

a fictionalized fundraiser.

The museum, led by figures like Arlene

Parr (former hospital librarian), has worked for over 30 years to

maintain accurate historical records. Books like Bittersweet Memories by

Gary L. Lisman and Parr provide personal accounts from patients and

staff, emphasizing the hospital’s human impact. The Alpha Park Public

Library’s podcast, Stories From the Bowen Building, features interviews

with former staff, further documenting the hospital’s legacy.

Peoria State Hospital was a pioneer in humane mental

health treatment, challenging the era’s brutal practices. Dr. Zeller’s

reforms, inspired by the Peoria Women’s League, set a national standard,

with the hospital’s nursing program and cure rates earning acclaim. Its

cottage system and open-door policy were radical, reflecting a belief

that no patient was incurable.

The hospital’s closure highlights

broader issues in mental health policy, particularly the shift to

deinstitutionalization without adequate community support, leaving many

patients vulnerable. Its paranormal lore, while sensationalized,

underscores the emotional weight of its history—thousands lived,

suffered, and died there, often forgotten except in numbered graves.

The preservation efforts, though challenged by demolitions, ensure

the hospital’s story endures. The museum and community initiatives keep

the focus on both the patients’ experiences and Zeller’s vision,

balancing historical education with the site’s eerie allure.

While sources like Wikipedia and the Peoria State Hospital Museum website provide detailed accounts, they may emphasize Zeller’s reforms and paranormal stories over systemic issues, such as the 94 lobotomies or the neglect caused by budget cuts in the 1960s. The narrative of Zeller as a reformer is compelling but risks idealizing the institution, which, despite its advances, was part of a broader system that often failed the mentally ill, especially post-closure. The focus on hauntings, while engaging, can overshadow the real human stories, as seen in Bittersweet Memories. Future research could explore patient records or oral histories to deepen understanding of life at the hospital beyond Zeller’s perspective.