Location: 10 mi (6 km) East of Torrey Map

Area: 241,904 acres (97,895 ha)

Info: (435) 425 3791

Open: Jun- Sept: 8am- 6pm daily

Oct- May: 8am- 4:30pm daily

Area: 241,904 acres

When to go: spring- fall

Activities:

camping, hiking, mountain biking

To see:

- Rim Overlook

trail

- hike to Sunset point

Capitol Reef National Park, located in south-central Utah, is a geological and cultural treasure spanning 241,904 acres across Wayne, Garfield, Sevier, and Emery counties. Established as a national monument in 1937 and upgraded to a national park in 1971, it is renowned for its vibrant desert landscapes, towering rock formations, and the Waterpocket Fold, a 100-mile-long monocline described as a “wrinkle in the Earth’s crust.” The park’s name derives from its white Navajo Sandstone domes, resembling capitol buildings, and the “reef-like” cliffs that once posed barriers to early travelers. Capitol Reef is a haven for hikers, geologists, photographers, and history buffs, offering over 150 miles of trails, ancient petroglyphs, pioneer orchards, and a glimpse into millions of years of Earth’s history. Managed by the National Park Service (NPS), it attracts over 1.2 million visitors annually (2023), balancing preservation with accessibility in a remote, rugged setting.

Capitol Reef’s defining feature, the Waterpocket Fold, formed 50–70 million years ago during the Laramide Orogeny, a period of mountain-building that shaped the Rocky Mountains. This S-shaped monocline, or “wrinkle in the Earth’s crust,” stretches from Thousand Lake Mountain to Lake Powell, exposing sedimentary rock layers spanning 270 million years, from the Permian to Cretaceous periods. These layers—Chinle’s red shales, Wingate’s crimson cliffs, Kayenta’s ledges, and Navajo Sandstone’s white domes—record ancient environments: tidal flats, deserts, and inland seas. The fold’s western cliffs, rising up to 7,000 feet, and its eastern waterpockets (natural basins holding rainwater) shaped human and ecological adaptations. Erosion, driven by the Fremont River and flash floods, carved canyons like Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge, creating the park’s dramatic topography.

Human history in Capitol Reef begins with Paleo-Indians, who arrived around 12,000 BCE, hunting megafauna like mammoths and bison in a cooler, wetter climate. Sparse evidence, such as Clovis points, suggests seasonal camps near springs. As the climate warmed by 7000 BCE, Archaic peoples adopted a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, exploiting plants like Indian ricegrass and animals like bighorn sheep. Their tools—metates, manos, and basketry—found in alcoves like Behunin Cabin’s overhang, indicate a mobile existence. These groups left no permanent structures but likely used the fold’s canyons as travel corridors, following game and water.

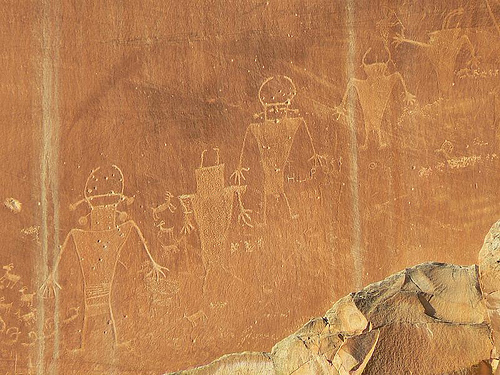

Around 300 CE, the Fremont culture, a semi-sedentary

people related to but distinct from the Ancestral Puebloans, settled

along the Fremont River, named for explorer John C. Frémont but central

to their livelihood. The Fremont combined agriculture—maize, beans,

squash—with hunting and gathering, irrigating small plots in Fruita and

Sulphur Creek. Their villages, often in sheltered alcoves, included pit

houses and granaries, some preserved in Capitol Gorge.

The

Fremont’s most enduring legacy is their rock art, found on canyon walls

along State Route 24 and in Hickman Bridge’s alcove. Petroglyphs, carved

into rock, and pictographs, painted with mineral pigments, depict

anthropomorphic figures, bighorn sheep, snakes, and geometric patterns,

possibly representing spiritual or astronomical themes. A notable panel

near Fruita, accessible via a boardwalk, shows tall, trapezoidal figures

with headdresses, suggesting ceremonial roles. Granaries, built high in

cliffs to store crops, reflect their ingenuity in a drought-prone

region.

By 1300 CE, the Fremont abandoned Capitol Reef, likely

due to prolonged droughts, climate shifts, or social pressures, possibly

migrating south or integrating with other groups. Their disappearance

coincided with broader Ancestral Puebloan migrations, leaving the region

sparsely populated by Southern Paiute and Ute bands, who used it

seasonally for hunting and gathering into the historic period.

European exploration began with the 1776 Dominguez-Escalante Expedition,

Spanish priests seeking a route from Santa Fe to Monterey. Their journal

mentions crossing near modern Green River, 100 miles northeast, but they

likely skirted Capitol Reef’s northern edge, noting the region’s

aridity. Fur trappers, including Jedediah Smith in the 1820s, traversed

Utah but left no specific record of the fold.

In 1853, Captain

John W. Gunnison, surveying a transcontinental railroad route, crossed

the Waterpocket Fold, describing its “broken and precipitous” terrain.

His expedition, killed by Paiutes in retaliation for settler violence,

highlighted the region’s dangers. John Wesley Powell’s 1869–1872

Colorado River surveys provided the first detailed geological accounts,

naming the Fremont River and describing the fold as a “profound

structural feature.” Powell’s assistant, Almon Harris Thompson, mapped

the area, calling it “Capitol Reef” for its white Navajo domes (like

capitol buildings) and reef-like cliffs.

The 1847 arrival of

Mormon pioneers in Utah, led by Brigham Young, set the stage for

settlement. The 1850s Rogue River Wars and Black Hawk War (1865–1872)

displaced Paiutes and Utes, with federal policies forcing them onto

reservations like the Uintah-Ouray. By 1870, the region was open to

Mormon colonization, though its remoteness delayed permanent settlement.

In the 1870s, Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City sent settlers to colonize

southern Utah, targeting fertile valleys. In 1880, the first

families—Nels Johnson, Elijah Behunin, and Franklin Young—established

Junction (renamed Fruita in 1902) along the Fremont River, 1 mile east

of the fold. The river’s reliable flow, unlike the intermittent Dirty

Devil or Muddy Creek, supported irrigation, transforming the valley into

an oasis. By 1884, 10 families, including the Oylers, Chesnuts, and

Meeks, lived in Fruita, growing alfalfa, sorghum, and orchards of

apples, pears, peaches, cherries, and apricots, preserved as a historic

landscape today.

Fruita’s settlers built log cabins, a blacksmith

shop, and irrigation ditches, some still visible near the Fruita

Campground. In 1896, they constructed a one-room schoolhouse, now

restored, serving 20–30 children. The community was tight-knit, with

shared labor and LDS Church activities at the schoolhouse, as no church

was built. Isolation—Torrey was 15 miles away via wagon trails—fostered

self-reliance, though settlers traded fruit and livestock with

Hanksville and Loa.

Interactions with Paiutes were limited but

notable. Some Paiutes traded baskets or worked as farmhands, but federal

removal policies and disease reduced their presence. Fruita’s small size

(50–70 residents at its peak) and defensive measures, like fortified

cabins, minimized conflicts during the Black Hawk War’s tail end.

By 1900, Fruita’s population stabilized at 10–12 families, with about 60

residents. The introduction of alfalfa and cattle diversified the

economy, but poor roads limited growth. In 1902, the name “Fruita” was

formalized, reflecting the orchards’ prominence, which yielded surplus

fruit sold in Salt Lake City. The 1908 arrival of Joseph Hickman, a

teacher, and Ephraim Portman Pectol, a Mormon bishop from Torrey, marked

a turning point. Pectol, fascinated by Fremont artifacts, began

collecting pottery and tools, storing them in his Torrey store and later

the Wayne County Courthouse.

In the 1910s, improved roads via the

1910 Automobile Highway (now UT-24) brought early tourists, drawn by

Charles Dutton’s 1880s geological writings describing “Capitol Dome” and

the fold’s “rainbow cliffs.” Pectol and Hickman, seeing tourism

potential, promoted the area as “Wayne Wonderland,” organizing trips for

locals and Utah officials. In 1921, Pectol, as president of the Wayne

County Commercial Club, escalated advocacy, publishing articles and

lobbying legislators. Hickman’s 1925 death in a car accident was a

setback, but Pectol, elected to the Utah Legislature in 1928, secured

state support.

The 1930s Great Depression spurred federal action.

In 1933, Pectol and his wife, Dorothy, hosted NPS officials, showcasing

Fremont sites and geological wonders. Their collection, donated to the

park in 1937, formed the basis of the Visitor Center’s museum. On August

2, 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed Wayne Wonderland

National Monument, covering 37,060 acres, recognizing its “extraordinary

geologic formations, fossil remains, and prehistoric Indian relics.”

The NPS assumed management in 1937, hiring Pectol as the first custodian

(1937–1941) at $1/year, with his wife as ranger-historian. The Civilian

Conservation Corps (CCC) built early infrastructure, including trails,

the Fruita Campground, and stone retaining walls, employing local men

during the Depression. In the 1940s–1950s, the NPS acquired Fruita’s

private lands, compensating families like the Oylers and Chesnuts. By

1969, the last resident, Merin Smith, sold his homestead for $15,000,

ending Fruita’s settlement era.

World War II delayed development,

but post-war tourism surged with Utah’s 1945 “Mighty Five” campaign

promoting its parks. In 1950, Charles Kelly, a historian and ranger,

documented Fruita’s history, advocating for orchard preservation. The

1958 Mission 66 program, an NPS initiative to upgrade facilities,

brought paved roads, the 1966 Visitor Center, and ranger housing.

Visitation grew from 11,000 in 1937 to 146,000 by 1969.

Geopolitical events influenced expansion. The 1950s Cold War uranium

boom in southern Utah, driven by Atomic Energy Commission incentives,

led to prospecting in Capitol Reef, with minor claims in Oyler Mine

(selenium, not uranium). Environmental concerns and scenic value

prompted conservationists, including the Sierra Club, to push for park

status. On January 20, 1969, President Lyndon B. Johnson expanded the

monument to 254,242 acres, adding Cathedral Valley, Halls Creek, and

Boulder Mountain.

On December 18, 1971, President Richard Nixon

signed Public Law 92-207, establishing Capitol Reef National Park,

adjusting boundaries to 241,904 acres to balance conservation and local

grazing interests. The legislation, backed by Utah Senator Frank Moss,

recognized the park’s geological, cultural, and recreational

significance, ensuring permanent protection.

Since 1971, Capitol Reef has grown into a major destination, with 1.29

million visitors in 2023, up from 500,000 in the 1990s. The NPS has

balanced access with preservation through:

Infrastructure: Paving

UT-24 and the Scenic Drive, expanding the Visitor Center (1990s), and

adding interpretive trails like the Fremont Petroglyph Boardwalk.

Orchard Maintenance: The park’s 2,700 fruit trees, a Historic Orchard

District since 1998, are pruned and replanted, yielding 100,000 pounds

of fruit annually for visitor picking ($2/pound, July–October). The

Gifford House (1908), restored as a museum and bakery, sells pies.

Cultural Protection: Fremont sites are monitored for vandalism, with

restricted access to sensitive granaries. The Pectol Collection,

including 1,000+ artifacts, is curated at the Visitor Center.

Wilderness Designation: In 1988, 14,000 acres were designated

wilderness, limiting motorized access to preserve solitude.

Environmental challenges include invasive species (tamarisk, Russian

olive), removed through NPS projects since the 2000s, and flash floods,

intensified by climate change, which damaged trails in 2022. Grazing,

permitted on 10% of the park under 1971 compromises, remains

contentious, with groups like the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance

advocating for its end due to soil erosion and native plant loss.

The park’s 2004 Dark Sky Park status, certified by the International

Dark-Sky Association, protects its pristine night skies, with ranger-led

stargazing drawing crowds. Visitation spikes strain resources, prompting

trail quotas and campground expansions. The 1996 General Management Plan

and 2020 Visitor Use Study guide sustainable tourism, capping

backcountry permits and promoting low-impact activities.

Cultural

efforts have grown inclusive. Since the 2010s, the NPS has partnered

with Southern Paiute and Ute tribes to incorporate their perspectives in

exhibits, acknowledging their displacement. The Capitol Reef Natural

History Association, founded in 1965, funds research, publishing guides

like Dee Woolley’s Geology of Capitol Reef (2005).

Fruita Historic District: Includes the 1896 schoolhouse, Gifford House

(1908), blacksmith shop, and orchards, preserved as a living pioneer

landscape.

Fremont Petroglyph Panels: Along UT-24 and Hickman Bridge

Trail, showcasing 1,000-year-old rock art.

Capitol Gorge: A historic

wagon route with pioneer inscriptions and Fremont granaries.

Pectol

Collection: Fremont artifacts at the Visitor Center, donated in 1937.

CCC Structures: Stone walls and trails near Fruita Campground, built in

the 1930s.

Capitol Reef’s history encapsulates:

Geological Time: The Waterpocket

Fold, exposing 270 million years, is a global geological benchmark,

studied since Powell’s surveys.

Fremont Legacy: Their rock art and

granaries, among Utah’s best-preserved, offer insights into a vanished

culture.

Mormon Resilience: Fruita’s orchards and irrigation reflect

pioneer ingenuity, a rare agricultural success in the desert.

Conservation Triumph: Pectol’s grassroots advocacy and NPS stewardship

transformed a remote valley into a national treasure, balancing human

history with wilderness.

The park’s role in the 20th-century

preservation movement, alongside Zion and Bryce Canyon, underscores

Utah’s scenic legacy. Its Native history, though disrupted, is

increasingly honored, enriching the narrative.

The park’s centerpiece is the Waterpocket Fold, a

nearly 100-mile-long monocline stretching from Thousand Lake Mountain in

the north to Lake Powell in the south. Formed 50–70 million years ago

during the Laramide Orogeny, this geological structure is a step-like

fold where older rock layers were thrust upward over younger ones along

a fault, creating a dramatic escarpment. The fold’s western side rises

sharply, forming cliffs up to 7,000 feet high, while the eastern side

slopes gently, resembling a ramp. Its S-shaped curve, one of the longest

exposed monoclines in the world, exposes a cross-section of sedimentary

rocks spanning 270 million years, from the Permian to Cretaceous

periods.

The fold’s name derives from “waterpockets,” natural

basins or potholes in the slickrock that collect rainwater, critical for

wildlife, plants, and early human travelers like the Fremont and Mormon

pioneers. These depressions, often 10–20 feet deep, are most abundant in

the fold’s southern reaches, such as Halls Creek Narrows, and sustain

life in an arid region.

Capitol Reef’s geology is a vivid archive of ancient

environments, with 10,000 feet of sedimentary strata revealing deserts,

tidal flats, and inland seas. Key formations, from oldest to youngest,

include:

Moenkopi Formation (250 million years ago,

Permian-Triassic): Reddish-brown shales and siltstones from tidal flats,

visible in Capitol Gorge and along the Scenic Drive. Ripple marks and

mudcracks preserve ancient shorelines.

Chinle Formation (225 million

years ago, Triassic): Colorful shales and mudstones, often purple,

green, or red due to volcanic ash and iron oxides, seen in Cathedral

Valley. Bentonite clay swells when wet, creating unstable slopes.

Wingate Sandstone (200 million years ago, Jurassic): Towering red

cliffs, up to 300 feet thick, from ancient sand dunes, forming the

park’s “reef” barriers. Prominent in Grand Wash and along UT-24.

Kayenta Formation (195 million years ago, Jurassic): Thin, ledgy

sandstones and shales from river floodplains, capping Wingate cliffs and

visible in Hickman Bridge.

Navajo Sandstone (190 million years ago,

Jurassic): White to cream-colored domes and spires, up to 2,000 feet

thick, from a vast desert erg. Its rounded shapes, like Capitol Dome,

inspired the park’s name and dominate Fruita’s skyline.

Carmel

Formation (170 million years ago, Jurassic): Red and gray limestones and

shales from shallow seas, forming thin layers above Navajo.

Entrada,

Curtis, and Summerville Formations (160–150 million years ago,

Jurassic): Red sandstones and shales in the park’s northern sections,

like Cathedral Valley’s Temple of the Sun.

Morrison Formation (145

million years ago, Jurassic-Cretaceous): Gray-green mudstones and

sandstones with dinosaur fossils, found in remote areas like Halls

Creek.

Dakota Sandstone and Mancos Shale (100–80 million years ago,

Cretaceous): Coal-bearing sandstones and marine shales in the park’s

highest elevations, like Boulder Mountain.

Igneous intrusions, like

basalt dikes and sills from 20–3 million years ago, cut through older

layers, visible as dark streaks in Miners Mountain. Fossils—marine

invertebrates in Moenkopi, dinosaur tracks in Kayenta, and petrified

wood in Chinle—add paleontological richness.

Erosion, driven by the Fremont River, Sulphur Creek,

and flash floods, has sculpted Capitol Reef’s iconic features:

Canyons: Narrow slot canyons like Grand Wash (1,000 feet deep, 15 feet

wide), Capitol Gorge, and Burro Wash, carved by episodic floods, offer

hiking routes and reveal layered geology.

Domes and Spires: Navajo

Sandstone’s rounded domes, like Capitol Dome and Chimney Rock, result

from differential erosion, while Wingate’s angular spires, like the

Castle, resist weathering.

Monoliths: Cathedral Valley’s freestanding

monoliths, Temple of the Sun and Temple of the Moon, rise 400–500 feet

from eroded Chinle mudstones.

Natural Arches: Hickman Bridge

(133-foot span) and Cassidy Arch (named for outlaw Butch Cassidy, who

hid nearby) form in Navajo and Kayenta layers where water erodes weak

points.

The fold’s asymmetry creates distinct landscapes: the west’s

steep cliffs challenge hikers, while the east’s gentle slopes host

waterpockets and rolling slickrock, ideal for backcountry exploration.

Capitol Reef’s topography ranges from low desert

valleys to alpine plateaus, with elevations from 3,800 feet at Halls

Creek in the south to 8,960 feet on Boulder Mountain in the northwest.

Key topographic zones include:

Fruita Historic District (5,500

feet): A flat, fertile valley along the Fremont River, home to orchards,

the Visitor Center, and UT-24. Surrounded by Navajo domes and Wingate

cliffs, it’s the park’s hub.

Cathedral Valley (6,000–7,000 feet): A

remote northern basin with eroded Chinle badlands and towering

monoliths, accessed via a 60-mile 4WD loop.

Waterpocket District

(4,000–5,500 feet): The fold’s southern third, with waterpockets, slot

canyons, and Halls Creek Narrows, a 9-mile chasm.

Miners Mountain

(7,835 feet): A central ridge offering panoramic views of the fold and

Henry Mountains.

Boulder Mountain (7,000–8,960 feet): A forested

plateau with aspen groves and alpine meadows, part of the Aquarius

Plateau, accessible via backcountry trails.

The park’s rugged

terrain, with 150 miles of trails, ranges from easy (1-mile Sunset

Point) to strenuous (16-mile Lower Muley Twist Canyon), catering to

varied skill levels. Vertical relief, like the 2,000-foot climb to Rim

Overlook, showcases the fold’s scale.

Water is scarce but vital in Capitol Reef’s arid

landscape, shaping its geography and ecology:

Fremont River: The

park’s primary waterway, originating in the Fishlake National Forest,

flows 95 miles through Fruita, carving a green corridor. Its reliable

flow supported Fremont agriculture and Mormon orchards, with irrigation

ditches still functional.

Sulphur Creek: A seasonal stream west of

the Visitor Center, forming a narrow canyon with waterfalls, popular for

hiking (5.8-mile round trip).

Halls Creek: A mostly dry wash in the

Waterpocket District, flowing only during monsoons, feeding waterpockets

critical for bighorn sheep.

Pleasant Creek: A perennial stream south

of Fruita, sustaining riparian zones and hiking trails.

Waterpockets:

Thousands of natural potholes, ranging from inches to 20 feet deep, dot

the fold’s slickrock, holding water for weeks after rains. They are

ecological lifelines and historically aided Paiute travelers.

Flash

floods, common in July–September monsoons, reshape canyons and pose

risks, as seen in 2022 trail closures. The park’s 7–11 inches of annual

precipitation, mostly summer storms, contrasts with its arid soils,

which retain little moisture, creating a stark desert environment.

Capitol Reef’s arid, high-desert climate is

characterized by extreme temperature swings and low precipitation:

Temperature: Summer highs average 90°F (July), with peaks over 100°F

in low elevations like Halls Creek. Winter lows average 20°F (January),

dipping to 0°F at night. Boulder Mountain is 10–15°F cooler year-round.

Precipitation: Annual rainfall averages 7 inches in Fruita and 11 inches

on Boulder Mountain, with 60% in July–September monsoons. Snowfall,

10–20 inches annually, dusts low elevations and accumulates (up to 40

inches) on higher peaks.

Winds: Spring winds, 20–40 mph, erode loose

soils, while calm nights enhance stargazing, earning the park’s 2004

Dark Sky Park status.

Seasonal Patterns: Spring (April–May) and fall

(September–October) offer mild temperatures (50–75°F) and vibrant

wildflowers or aspen colors. Summer brings heat and flash flood risks,

while winter provides solitude but icy trails.

Climate change

intensifies monsoons and drought cycles, threatening orchards and

trails. The NPS monitors flood risks, closing slot canyons during heavy

rains.

Capitol Reef’s elevation range (3,800–8,960 feet)

creates five ecological zones, each with distinct flora and fauna:

Lower Desert (3,800–5,000 feet, Halls Creek): Creosote bush,

blackbrush, and cacti (prickly pear, claret cup) dominate sandy soils.

Lizards (collared, side-blotched), snakes (gopher, rattlesnake), and

rodents (kangaroo rat) thrive. Annual wildflowers like desert marigold

bloom after rains.

Upper Desert (5,000–6,500 feet, Fruita, Grand

Wash): Pinyon pine, Utah juniper, and sagebrush form open woodlands.

Mule deer, coyotes, and birds (pinyon jay, canyon wren) are common.

Cottonwoods and willows line the Fremont River, supporting beavers and

warblers.

Shrub-Steppe (6,500–7,500 feet, Cathedral Valley): Big

sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and grasses cover rolling hills. Pronghorn,

jackrabbits, and raptors (red-tailed hawk) roam. Ephemeral pools host

fairy shrimp.

Woodland (7,500–8,500 feet, Miners Mountain): Ponderosa

pine, Gambel oak, and manzanita create dense forests. Black bears,

mountain lions, and wild turkeys are rare but present. Spring

wildflowers include paintbrush and lupine.

Alpine (8,500–8,960 feet,

Boulder Mountain): Aspen groves, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine meadows

host columbine and penstemon. Elk, marmots, and Clark’s nutcrackers

inhabit this zone, with snow lingering into June.

The park supports

22 mammal species, 160 birds, 16 reptiles, 6 amphibians, and 1,000+

plant species, including 40 endemics like the Capitol Reef primrose.

Reintroduced bighorn sheep (100–150) graze slickrock, while invasive

tamarisk and Russian olive threaten riparian areas, prompting NPS

removal efforts since the 2000s.

Capitol Reef’s human geography centers on the Fruita

Historic District, a 200-acre oasis along the Fremont River at 5,500

feet, where Mormon pioneers established orchards in the 1880s. The

district, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, includes

2,700 fruit trees, the 1896 schoolhouse, Gifford House (1908), and

irrigation ditches, preserved as a living cultural landscape. The

Visitor Center, Fruita Campground (71 sites), and UT-24 form the park’s

core, with 80% of visitors concentrating here.

Other developed

areas are minimal:

Cathedral Valley: A remote northern section with a

primitive campground (6 sites, free, first-come) and the 60-mile

Cathedral Valley Loop (4WD required).

Waterpocket District:

Backcountry-focused, with Halls Creek Overlook and a small ranger

contact station.

Backcountry: 14,000 acres of designated wilderness,

added in 1988, restrict motorized use, preserving solitude in areas like

Upper Muley Twist Canyon.

The park’s boundaries enclose 378 square

miles, with 98% federally owned. Private inholdings, mostly grazing

leases, cover 2%, a legacy of 1971 compromises with ranchers. Grazing,

permitted on 10% of the park, impacts soils and native plants, sparking

debate among conservationists.

Capitol Reef encapsulates layers of human history:

Fremont Culture: Petroglyphs and granaries reveal a sophisticated

society, with rock art as a cultural legacy.

Mormon Pioneers:

Fruita’s orchards and irrigation systems reflect resilience in a harsh

environment, preserved as a living historic site.

Geological Study:

The Waterpocket Fold is a global case study, attracting researchers

since Powell’s surveys.

Conservation: The park’s creation reflects

early 20th-century preservation movements, balancing human use with

wilderness protection.

The park’s 14,000 acres of designated

wilderness, added in 1988, underscore its pristine character, while

Fruita’s orchards connect visitors to pioneer life. Native perspectives,

particularly Paiute and Ute, are increasingly integrated into

interpretive programs, acknowledging their displacement.

Capitol Reef offers diverse activities, centered

around the Fruita Historic District along State Route 24:

Hiking:

Over 150 miles of trails, from easy (1-mile Sunset Point) to strenuous

(9-mile Upper Muley Twist Canyon). Popular routes include Hickman Bridge

(1.8 miles, 400-foot gain) and Cassidy Arch (3.4 miles, named for Butch

Cassidy, who hid nearby).

Scenic Drives: The 8-mile Scenic Drive

($20/vehicle, paved/gravel) winds through the fold, with spurs to Grand

Wash and Capitol Gorge. The 60-mile Cathedral Valley Loop (4WD

recommended) showcases remote monoliths.

Orchards: Visitors can pick

fruit in season (July–October, $2/pound), with ladders and tools

provided. The Gifford House sells pies and preserves.

Cultural Sites:

The Fruita Schoolhouse, Gifford House, and petroglyph panels are

accessible via short walks. The Ripple Rock Nature Center offers kids’

programs.

Stargazing: As a Dark Sky Park, Capitol Reef hosts

ranger-led astronomy talks, with Milky Way views from Panorama Point.

Climbing and Canyoneering: Technical routes in Wingate cliffs and slot

canyons require permits ($6–$15).

The Visitor Center, near Fruita

Campground, provides maps, exhibits, and a 20-minute film (open 8

a.m.–4:30 p.m., extended summer hours). Ranger-led talks and guided

hikes run April–October. The park is open year-round, with spring

(April–May) and fall (September–October) ideal for mild weather and

blooms. Summer brings crowds and heat (90°F), while winter (20–40°F)

offers solitude but icy trails.

By Car: From Salt Lake City (230 miles, 3.5 hours),

take I-15 south to UT-20, then UT-24 east. From St. George (200 miles),

take I-15 north to UT-9, then UT-24. UT-24 bisects the park, connecting

Torrey (11 miles west) and Hanksville (37 miles east). Roads are paved

except for backcountry routes like Cathedral Valley, requiring

high-clearance 4WD.

Public Transit: No direct service. The nearest

airports are Grand Junction, CO (190 miles), and Salt Lake City.

Shuttles from Las Vegas or Moab require private booking.

Facilities:

Fruita Campground ($25/night, 71 sites, first-come, first-served) has

water and restrooms. Backcountry camping requires free permits. No

lodging or food is in the park; Torrey offers motels and dining (e.g.,

Capitol Reef Inn & Cafe). Gas is available in Torrey or Hanksville.

Fees: No entry fee for UT-24, but the Scenic Drive costs $20/vehicle

(valid 7 days). America the Beautiful Pass ($80/year) covers all NPS

sites.

Capitol Reef faces pressures from increased visitation

(1.29 million in 2023, up 60% since 2010), straining trails,

campgrounds, and orchards. Flash floods, intensified by climate change,

damage roads and trails, as seen in 2022 closures. The NPS mitigates

impacts through trail maintenance, visitor caps on sensitive routes, and

invasive species removal. Grazing, permitted on 10% of the park, sparks

debate over ecological harm, with advocacy groups pushing for

phase-outs.

Preservation efforts include stabilizing Fruita’s

historic structures and protecting Fremont sites from vandalism. The

Capitol Reef Natural History Association funds research and education,

while the park’s wilderness designation limits motorized access,

preserving solitude.

Timing: Visit spring or fall for ideal weather

(50–70°F) and fewer crowds. Allow 2–3 days for hiking, drives, and

orchards. Summer requires early starts to avoid heat; winter needs

traction devices for icy trails.

Preparation: Bring water (1

gallon/person/day), sunscreen, hats, and hiking boots. Cell service is

unreliable; carry paper maps. Check weather for flash flood risks

(nps.gov/care).

Safety: Stay hydrated; heat exhaustion is common.

Avoid slot canyons during rain. Watch for rattlesnakes and loose rock on

trails. Altitude (5,000–9,000 feet) may affect breathing.

Respect: Do

not touch petroglyphs or pick unripe fruit. Pack out all trash.

Backcountry campers must use designated sites or stay 0.5 miles from

roads.

Nearby: Torrey’s Rim Rock Restaurant and Hanksville’s Stan’s

Burger Shak offer dining. Goblin Valley State Park (70 miles) and Grand

Staircase-Escalante (100 miles) complement a visit.

Events: Check for

Harvest Festivals (September) or geology talks (summer). The Wayne

County Fair (August) in Loa (20 miles) adds local flavor.