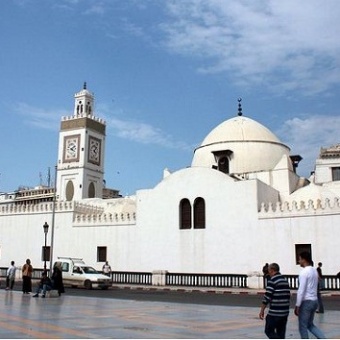

Place des Martyrs

The New Mosque (Djamaa el-Djedid), also known as the Mosque of the Fisherman’s Wharf (Mesdjed el-Haoutin) or Pêcherie Mosque, is one of the most significant historical and architectural landmarks in Algiers, the capital of Algeria. Despite its name, it is not new; it was constructed in 1660 CE (1070 AH) during the Ottoman period under the patronage of al-Hajj Habib, a Janissary governor appointed by the Ottoman administration in Constantinople. Located in the lower Casbah district near the port, its proximity to the fishing harbor earned it the nickname "Mosque of the Fisherman." This mosque is a remarkable example of Ottoman architecture blended with North African, Andalusian, and Byzantine influences, making it a unique cultural and religious monument.

The Djamaa el-Djedid was built during the Ottoman Regency of Algiers,

a period when the city was a major hub of trade, piracy, and cultural

exchange in the Mediterranean. The mosque was constructed on the site of

an earlier Quranic school, the Madrasa Bou Anan, and possibly near a

smaller mosque known as Mesdjed el-Haoutin ("Mosque of the Fishermen").

An inscription above the main entrance portal, dated 1660, credits

al-Hajj Habib with its construction, emphasizing his devotion to the

Hanafi rite, which the mosque continues to serve as a major temple

today.

During French colonial rule (1830–1962), the mosque was

renamed Mosquée de la Pêcherie, reflecting its location near the fishing

port. Unlike many Ottoman-era structures demolished by French urban

planners, the Djamaa el-Djedid was preserved, likely due to its

religious and cultural significance. It survived the redesign of the

Algiers waterfront, which created the Place des Martyrs, where the

mosque now forms the eastern edge.

The mosque has undergone

several reconstructions and renovations over the centuries, particularly

during the French period and after Algerian independence in 1962.

Despite these changes, it has retained its original name and much of its

architectural character, making it a enduring symbol of Algiers’ Ottoman

heritage.

The Djamaa el-Djedid is renowned for its eclectic architectural

style, which combines Ottoman, North African (Maghrebi), Andalusian,

Byzantine, and Italian influences. This fusion reflects Algiers’

position as a crossroads of Mediterranean cultures during the 17th

century. Below is a detailed breakdown of its architectural

elements:

Overall Layout

Basilical Plan with Latin Cross

Shape: The mosque’s floor plan is basilical, with three naves

perpendicular to the qibla wall, intersected by five bays. The

central nave and the penultimate bay are elevated, forming a Latin

cross at roof level. This unusual design has fueled a local legend

that the architect was a Christian who subtly incorporated a cross,

though scholars attribute the design to al-Hajj Habib, a Muslim

master builder adhering to Ottoman models. The cross shape likely

served a practical purpose: to elongate the prayer hall and

accommodate more worshippers.

Dimensions and Scale: The mosque is

relatively compact compared to later grand mosques, but its central

dome and minaret give it a commanding presence. The prayer hall is

spacious, with a large central nave and side aisles, designed to

serve the Hanafi community.

Dome and Cupolas

Central Dome:

The mosque’s most striking feature is its ovoid central dome, which

rises to a height of 24 meters at its intrados (inner surface). It

rests on four sturdy pillars via a drum and four pendentives, a

classic Ottoman and Byzantine technique. The dome’s slightly pointed

profile recalls the Syrian Church of Saint George in Ezra.

Octagonal Cupolas: At the four corners of the central dome, four

square spaces are covered by octagonal cupolas, each resting on an

octagonal drum and pendentives. These cupolas are smaller and

complement the central dome, creating a harmonious roofline.

Vaulting: The spaces between the cupolas are covered by barrel

vaults on three sides, while the fourth side, facing the qibla wall,

features a vault with three bays flanked by two aisles. This

arrangement enhances the mosque’s spatial complexity and draws

attention to the qibla.

Mihrab and Minbar

Mihrab: The

mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) is octagonal,

topped with a cul-de-four (quarter-dome). Its lower section is

adorned with ceramic tiles framed by two marble plinths, reflecting

Andalusian decorative traditions. The mihrab’s arch design also

shows Andalusian influence, with intricate geometric and arabesque

patterns.

Minbar: The marble minbar (pulpit) is a masterpiece of

craftsmanship, imported from Italy and originally part of the

al-Sayyida Mosque, which was destroyed in 1832. Unlike traditional

North African minbars made of wood, this marble minbar reflects

Ottoman preferences, though its design retains Maghrebi elements.

Minaret

The minaret is a square tower, a hallmark of North

African architecture, standing at 25 meters today (originally 30

meters, reduced due to rising street levels). It is crowned with a

ceramic frieze and a lantern, giving it an elegant Maghrebi

silhouette. Unlike the Ottoman-style body of the mosque, the minaret

aligns with local traditions, similar to those of the Ketchaoua and

Ali Bitchin mosques in Algiers. A clock, added by French architect

Bournichon during colonial rule, was repurposed from the Palais

Jenina.

Materials and Decoration

Exterior: The mosque’s

exterior is entirely whitewashed, including the domes and cupolas,

creating a striking, unified appearance. A thin line of colored

tiles trims the decorative ramparts facing the Place des Martyrs,

providing a subtle contrast. The structure is built with stone,

marble, brick, and plaster.

Interior: The interior is richly

decorated with ceramic tiles, woodwork, and marble columns. Some

columns are repurposed from Byzantine basilicas in the Algiers

region, adding historical depth. Carvings in the interior show

Italian influences, particularly in the ornate details, while the

overall aesthetic adheres to Ottoman and Andalusian models.

Columns and Capitals: The mosque features solid marble columns with

capitals taken from Byzantine ruins, a testament to the region’s

layered history. These columns support the arches and vaults,

contributing to the mosque’s robust yet elegant structure.

Entrances

The mosque has two main entrances: one opening onto the

Place des Martyrs and another on the ramparts leading to the port.

These entrances reflect its role as a community hub, accessible to

both the city’s residents and fishermen. A third entrance, less

prominent, serves the lower Casbah.

Hanafi Rite: The Djamaa el-Djedid remains the primary Hanafi mosque

in Algiers, serving the community that follows this school of Islamic

jurisprudence, which was dominant during Ottoman rule. Its religious

importance is underscored by its large prayer hall and historical role

as a congregational mosque.

Cultural Fusion: The mosque’s

architecture embodies Algiers’ cosmopolitan character in the 17th

century. The blend of Ottoman, Maghrebi, Andalusian, Byzantine, and

Italian elements reflects the city’s role as a melting pot of

Mediterranean cultures. Scholars suggest that the mosque’s unique design

may stem from Algiers’ distance from Istanbul, allowing local builders

to incorporate regional traditions.

Symbol of Resilience: The

mosque’s survival through French colonization, urban redevelopment, and

modern challenges (such as the nearby metro construction) highlights its

enduring significance. It stands as one of the few Ottoman-era buildings

spared during the French redesign of the waterfront.

Local Legends:

The Latin cross plan has inspired myths that a Christian architect

designed the mosque and was executed for embedding a Christian symbol.

However, historical evidence points to al-Hajj Habib, a Muslim builder,

as the mastermind, with the cross shape likely a practical design

choice.

Geographical Context: The mosque is situated in the lower Casbah, a

UNESCO World Heritage site, near the port of Algiers. Its qibla wall

faces Amilcar Cabral Boulevard, a busy thoroughfare, while the mosque

itself borders the Place des Martyrs, a central plaza created during

French rule. The Almoravid Great Mosque of Algiers (c. 1097 CE) is just

70 meters to the east, making this area a historic religious hub.

Proximity to the Sea: The mosque’s nickname, "Mosque of the Fisherman,"

derives from its location near the fishing harbor, where local fishermen

historically attended prayers. The Bab al-Bahr (Gate of the Sea) and the

original Mesdjed el-Haoutin were nearby, reinforcing its maritime

connection.

Urban Integration: The mosque is a focal point of the

lower Casbah, surrounded by historic sites like the Ketchaoua Mosque,

Dar Aziza, and the Palais des Raïs. Its accessibility via the Place des

Martyrs metro station makes it a popular stop for visitors exploring

Algiers’ old city.

Condition: The mosque is well-preserved, with ongoing maintenance to

protect its historical and architectural integrity. Some reviewers note

that the nearby metro construction has slightly altered its

surroundings, but the structure itself remains intact.

Accessibility:

The mosque is open to non-Muslims outside of prayer times, though

visitors are advised to take a local guide for a richer experience and

to navigate cultural norms. It is family-friendly, suitable for groups,

and accessible 24 hours, though prayer times may restrict entry.

Visitor Reviews: The mosque receives high praise for its architectural

beauty and historical significance, with ratings averaging 4.7/5 on

platforms like Safarway and Top-Rated.Online. Visitors describe it as a

“superb mosque” and an “architectural masterpiece” that enhances the

heart of Algiers.

Activities: Beyond worship, the mosque serves as a

cultural landmark, attracting tourists interested in Islamic

architecture, Ottoman history, and Algiers’ Casbah. Its proximity to

other attractions makes it easy to combine with visits to the Great

Mosque, Ketchaoua Mosque, or the National Museum of Decorative Arts.

While the Djamaa el-Djedid is often celebrated for its Ottoman

character, its architectural uniqueness stems from its divergence from

strict Ottoman norms. Scholars argue that Algiers’ distance from

Istanbul allowed for a creative synthesis of local and Mediterranean

traditions, evident in the minaret’s Maghrebi style, the mihrab’s

Andalusian arch, and the Byzantine-inspired dome structure. This

blending challenges the narrative of a purely Ottoman mosque, suggesting

instead a distinctly Algerian monument shaped by global influences.

The legend of the Christian architect, while debunked, reflects the

mosque’s ability to inspire storytelling and cultural debate. Its

survival through colonial and modern transformations underscores its

role as a resilient symbol of Algerian identity, though some critics

argue that urban developments, like the metro, have slightly diminished

its historical ambiance.