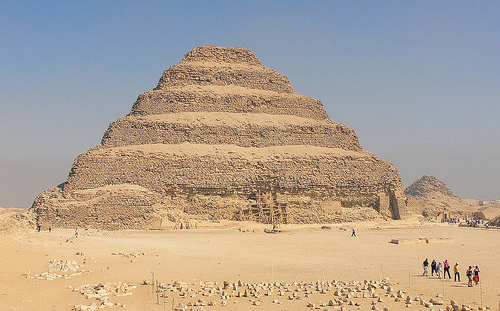

Location: Northwest of Mephis Map

Constructed: 2667–2648 BC during 5th dynasty by vizier (adviser) of Djoser- Imhotep

Height: 62 metres (203 ft)

The step pyramid of the ancient Egyptian King Djoser (Djoser

Pyramid, also Netjerichet Pyramid) from the 3rd Dynasty of the Old

Kingdom around 2700 BC. It is the oldest, with a height of 62.5

meters, the ninth highest of the Egyptian pyramids and one of the

few with a non-square base.

This building began the first

phase of pyramid construction in Egypt and the monumentalization of

the royal tombs. The step pyramid itself is enclosed by the largest

of all pyramid complexes, which contains a large number of

ceremonial buildings, structures and courtyards for the cult of the

dead. After Gisr el-Mudir, which is located a few hundred meters

west of the pyramid, it is considered the second oldest surviving

building made of carved stone in Egypt.

As the central

structure of the Sakkara necropolis, it has been a UNESCO World

Heritage Site since 1979 as part of the Memphite necropolises.

The pyramid complex was first examined in 1821 by the

Prussian Consul General Heinrich Menu Freiherr von Minutoli and the

Italian engineer Girolanio Segato. The entrance to the pyramid was

discovered. In the corridors, in one corner, the remains of a mummy were

found, namely a gilded skull and gilded soles, which Minutoli believed

to be the remains of the pharaoh. Although the objects were lost in the

Gottfried's shipwreck during the voyage to Hamburg, it is certain that

they were secondary burials from a later period.

In 1837 John

Shae Perring found numerous other secondary burials in the corridors. He

also discovered the galleries beneath the pyramid.

Beginning in

1926, Cecil M. Firth conducted a more systematic investigation, which he

was unable to complete due to his death. James Edward Quibell took over

the management of the excavations until he also died in 1935.

Jean-Philippe Lauer, who worked with Quibell, continued the

investigation. Lauer measured the underground chambers and passages in

1932. In 1934 he found additional body fragments in the burial chamber,

which, after an initial examination, were stored in the University of

Cairo until 1988. Lauer believed he had found the pharaoh's remains, but

closer examination after their discovery revealed that they came from

several people. Radiocarbon dating showed that the body parts came from

a secondary burial from the Ptolemaic era.

Lauer dedicated his

life until his death in 2001 to researching the Djoser pyramid and the

necropolis of Saqqara. Under Lauer's leadership, various buildings and

wall sections in the complex were reconstructed.

Research by a

Latvian team led by Bruno Deslandes has been able to detect several

previously unknown tunnels in the pyramid complex since 2001.

Djoser, who was known in his time by his Horus name

Netjerichet, had his tomb planned and built by Imhotep (high priest of

Heliopolis), Iri-pat ("member of the elite", chief reader, chief

sculptor and construction manager).

Circumstances of construction

During his 19-year reign (approx. 2665-2645 BC), Djoser had a monumental

tomb that had never been seen before built. This period was apparently

characterized by political stability, increasing prosperity and advances

in science and construction.

When choosing the location for his

tomb, Djoser chose the necropolis of Saqqara. The pyramid complex was

located near the tombs of the Second Dynasty kings Hetepsechemui, or

Raneb and Ninetjer, and the great enclosure of Gisr el-Mudir, away from

the First Dynasty mastaba tombs. However, the complex was not built on

untouched land; there was already an older necropolis on the site, as

evidenced by stair graves in the northern area.

The pyramid complex did not arise spontaneously, but

represents a synthesis of various Upper and Lower Egyptian burial

practices. It was the preliminary highlight in the development of the

tomb complexes of the kings of the 1st and 2nd dynasties from Abydos.

The step pyramid and its surrounding structures represent a combination

of the two components of the grave building and the valley area.

However, elements of the tombs and complexes of the Saqqara necropolis

can also be found. The large enclosure (Gisr el-Mudir), as the stone

equivalent of the valley districts of Abydos, probably served as a model

for the enclosure of the pyramid district. Likewise, the gallery tombs

of the Second Dynasty in Saqqara are models for the extensive galleries

in the Djoser pyramid district.

The pyramid itself is a further

development of the burial mounds symbolizing the mythological

“primordial mound”, as found in royal tombs in Abydos. The mound

structure was also incorporated into the mastaba tombs of Saqqara. This

is how you find e.g. B. within the mastaba S3507 there is a hidden

burial mound. In Mastaba S3038, this inner burial mound was recreated by

a stepped brick mound, which is a direct predecessor structure to the

pyramid.

The step pyramid is located in the center of the grave

area. However, it was not originally planned by Imhotep as a pyramid,

but as a square mastaba.

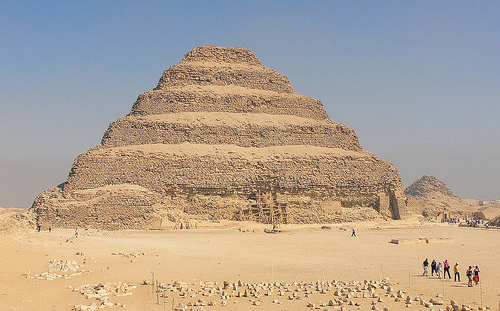

Development from the mastaba to the step

pyramid

According to Jean-Philippe Lauer, the mastaba was expanded

into a step pyramid in five further construction phases (six in total).

On the south and east sides of the pyramid, the individual phases of the

expansion can still be clearly seen. With the completion of the six

construction phases, the step pyramid received six steps and reached a

height of around 62 m, with a rectangular base of around 121 × 109 m.

The following construction phases can be distinguished:

Mastaba

M1: In the first step, a square mastaba with an edge length of 63 meters

and a height of eight meters was built, which differed from earlier

mastabas in two essential points: firstly, all previous mastabas had a

rectangular but not square floor plan and secondly, the Djoser- Mastaba

was the first to be made entirely of limestone. The Mastaba M1 received

an external cladding made of fine limestone. The substructure was

already carved out of the rock under the structure for this phase. The

shaft of the burial chamber ran through the structure to the roof of the

mastaba.

Mastaba M2: In the second phase, the mastaba was expanded to

an edge dimension of 71.5 m. However, the new component only reached a

height of seven meters, creating a stepped appearance. In this

construction phase, the eleven galleries on the east side of the mastaba

were created.

Mastaba M3: The third construction phase extended the

mastaba to 79.5 m only on the east side, so that the shafts of the east

galleries were covered by the new component, which was only five meters

high.

Pyramid P1: The fourth construction phase converted the mastaba

into a four-tiered step pyramid measuring 85.5 m × 77 m. The core of the

building was made of coarse stones and covered with more finely crafted

stones. The wall layers were now no longer horizontal as in the

mastabas, but rather inclined inwards by 17° in order to give the

masonry more stability. This phase did not rise above the height of the

original mastaba.

Pyramid P1': In the fifth phase, the small pyramid

was covered by a four- or six-stage pyramid with a base area of 119 m ×

107 m. As a result of this expansion, the original access to the

substructure was no longer accessible and a second access was created,

which came to the surface in the floor of the mortuary temple on the

north side. Significantly larger stones were now used in the masonry. In

this phase, too, only the first stage was completed before another

expansion began.

Pyramid P2: The sixth and final construction phase

enlarged the pyramid again to a base area of 121 m × 109 m (231 to 208

cubits) with a total of six steps, which reached a height of 62.50 m. In

the west, the lowest level rests on the already constructed western

massifs. The top step had a rounded end and, together with the pyramid

core, forms a flat surface. Therefore, there probably was no pyramid

top.

In addition to the core buildings for the four- and six-tiered

pyramid, Lauer specifies seven and eleven layers respectively, excluding

the outermost cladding layer. He is of the opinion that the cladding

layers for construction stages P1 and P2 were only installed after the

individual layers had been completed. The pyramid P1 was therefore

completely built before the last expansion with the pyramid P2. The

question of whether the pyramid had a smoothed outer surface is answered

in the negative by Stadelmann. Furthermore, excavations at the NW corner

of the pyramid in 2007 show that there were no remains of any limestone

cladding.

The burial chamber was created in a 28 m deep shaft with an area of 7

× 7 m. It consists of precisely hewn rose granite blocks in four layers.

Access to the burial chamber was from a so-called “maneuvering chamber”

above it through a circular hole about one meter in diameter. The access

was closed with a 3.5 ton granite plug that was lowered from the

maneuvering chamber with ropes. Finds of alabaster and limestone

fragments with a star pattern around the burial chamber suggest that

these are remains of the maneuvering chamber, as the material and

decoration are similar to that of the maneuvering chamber in the

southern tomb. Lauer, however, suspected that the granite burial chamber

replaced a burial chamber that had been installed in an earlier

construction phase.

After the burial and maneuvering chambers had

been inserted into the shaft, the shaft was walled up around the

chambers, then largely filled with loose material and the upper end was

walled up again. The filling and the maneuvering chamber were cleared

out in the 26th Dynasty (Saïte period).

A gallery complex is laid

out around the burial chamber in all directions. The individual

galleries are connected to each other with corridors. In the eastern

gallery there are four rooms lined with blue faience tiles, similar to

those in the south tomb. The tiles, separated by raised spaces, imitate

reed curtains. The blue tiles express the watery character of the

underworld in Egyptian mythology. There are also three bas-reliefs

depicting the king at the Sed festival. The complex appears unfinished -

especially in comparison to the southern tomb.

The second

substructure consists of the eleven east galleries. In the second

construction phase of the mastaba (M2), eleven shafts, each 30 m deep,

were dug on the east side, each of which has a gallery corridor running

in a westerly direction below the actual substructure. The excavators

numbered the corridors from north to south. The middle galleries are

each curved outwards so that the area of the central shaft of the

primary substructure is avoided. The first five shafts (I-V) were used

to bury members of the pharaoh's family and were looted in ancient

times. Two alabaster sarcophagi as well as fragments of other sarcophagi

and grave goods were found in the corridors.

However, the

remaining shafts were intact and contained over 40,000 ceramic and

alabaster vessels, identified by inscriptions as grave goods from the

1st and 2nd dynasties. Although largely broken by the collapse of the

ceilings, these objects constitute an important source of art from the

Early Dynastic period. It may be a reburial of grave goods from damaged

old graves restored by Djoser. The reason why these vessels, but not

other grave goods, were placed in the galleries of Djoser's tomb has not

yet been clarified.

The Djoser Pyramid complex is the largest of all Egyptian pyramids

and covers approximately 15 hectares. When executing the elements of the

complex, some were executed in functional architecture, but others in

what is known as fictional architecture. While the former buildings

probably had a function in the burial ceremony, the latter served the

pharaoh's Ka in the afterlife. It was enough that the exterior of the

elements had the correct appearance, while the interior could be

neglected.

It is striking that certain elements of Egyptian

architecture, which in this world's architecture consist of perishable

materials such as wood and reed mats, are not missing here, but have

been reproduced in stone without any function.

The pyramid

complex, like the pyramid, was built in two construction phases. The

dimensions of the original, smaller pyramid district can be seen from

the wall foundations north of the pyramid. In the east, this first

construction phase was probably limited to the western massifs.

The entire district is also surrounded by a large, 40 m wide ditch.

This reaches an extent of 750 m in a north-south direction. The depth of

the trench is not known as previous excavations have only been carried

out to a depth of five meters. On the south side, the trench carved out

of the rock is not self-contained, but the western wing is slightly

shorter, creating an overlap. The entrance to the complex was probably

between the ends of the ditch. During excavations in the southern area,

an Egyptian research team was able to prove that the walls of the trench

were provided with niches. Today the ditch is largely buried, but can be

clearly seen on aerial photographs.

According to Swelim, the

niches could represent a symbolic replacement for the secondary tombs of

the 1st Dynasty, which took the deceased pharaoh's servants with them

into the afterlife.

In addition to the symbolic function, it is

possible that the ditch served as a quarry for the material used in the

pyramid complex. This theory is supported by the fact that no other

traces of the excavated material were found.

In the space between

the northeast corner of the moat and the wall of the Djoser complex,

Userkaf built his pyramid in the 5th Dynasty. Unas built his pyramid

complex directly west of the entrance. The large ditch was probably

already largely buried by this time.

The grave area is surrounded by a 1,645 m long and approx. 10.5 m

high limestone wall in palace facade architecture, which is divided by

niches and 14 false gates. As with the valley districts in Abydos, the

actual entrance to the burial district is in the southeast corner of the

surrounding wall. The wall encloses an area of 15 hectares and therefore

has an area that corresponds to a larger city of the time. In a

north-south direction the extent is 545 m, in an east-west direction it

is 278 m.

The wall consists of a core of loosely laid masonry,

completely faced on the outside and partially faced on the inside with

fine limestone. An equally wide bastion protrudes from the wall every

four meters. The bastions around the entrance and the false gates are

wider. There are three false gates on the north and south sides, four on

the west side and four false gates as well as the real entrance on the

east side.

The wall is different from the enclosures of the

valley districts at Abydos, but is similar to those of the archaic

mastabas at Saqqara. According to Lauer, the wall could have been a

replica of the palace in the then capital Inebu-Hedj (White Walls), but

this has not yet been confirmed because this palace has not yet been

found. Some other Egyptologists suggest that it may be a replica of a

Lower Egyptian palace made of mud bricks, as the wall's building blocks

are similar in size to typical mud bricks.

The entrance area consists of the entrance gate, the colonnade and

the portico to the courtyard.

The colonnade is not oriented

exactly in an east-west direction, which is attributed to the fact that

it was built along a no longer existing "leaning" building that was

located between the south wall and the colonnade. A total of 20 pairs of

columns form the colonnade. The limestone columns, which were

approximately six meters high, were each composed of several shorter

segments. Apparently not relying on the sole load-bearing capacity of

the columns, they were connected to the wall behind them. The surface of

the columns imitates plant material; According to Lauer, bundles of

reeds could have supported light roofs at that time, or according to

Ricke, palm leaf ribs that were used as protection on mud brick

buildings. The colonnade is divided into two areas of different lengths

between the twelfth and thirteenth pair of columns. Between the columns

and the walls there are 24 niches, which, according to some

Egyptologists, could represent chapels for the provinces of the empire.

In the west, the colonnade ends in a portico to the south courtyard,

which is formed by four shorter columns. The remains of red paint were

still found on the portico columns.

The investigation of the area

revealed that it was not built in one step, but in several stages.

Fragments of Djoser's statues were also found there, the inscriptions of

which attest to the Horus name Netjerichet and the name Imhotep, which

proves the builders.

Lauer reconstructed the entrance area

between 1946 and 1956.

The South Tomb represents one of the most enigmatic elements of the

Djoser pyramid complex. The structure consists of a massive, elongated

mastaba-like block of limestone masonry on the south side of the

courtyard. At right angles to the mastaba superstructure there is a cult

chapel in the northwest, which borders on the western massif. Their

facades, which are visible towards the courtyard, have niches and are

decorated with a cobra frieze.

The substructure of the south

grave represented a slightly smaller and simplified version of the

substructure of the main grave, but with an east-west orientation. A

descending corridor leads to a rose granite burial chamber, which

appears to be a reduced copy of the main burial chamber. The length of

the chamber is 1.6 m. The maneuvering space above the chamber is

preserved here. The descending corridor leads further into a gallery,

which, like the main grave, was also partly decorated with blue faience

tiles. There are also three false doors with door scrolls, each of which

depicts the Pharaoh in scenes from the Sed festival.

The

significance of the southern grave is still unclear. According to Firth

and Edwards it could be a temporary grave, but according to Ricke and

Jéquier a symbolic Ka grave is also conceivable. As a last resort, the

southern grave would represent a forerunner of the later cult pyramids.

It is not clear whether a burial took place in the south grave.

The southern courtyard is the largest open area in the Djoser

complex. A few buildings can be found there. In the north, directly at

the pyramid, there is an altar. The remains of a small temple can be

found in the northeast corner. On the area of the farm there were two

limestone buildings with a “B”-shaped floor plan. The purpose of these

objects is still unclear, but there could be a connection to the

symbolic course of the Sed festival (Heb-Sed).

In the area of the

southern courtyard, a limestone block was found during excavations, the

inscription of which attests to the restoration of the complex in the

19th dynasty by Chaemwaset, a son of Ramesses II. Numerous buildings and

monuments in the necropolises near Memphis have inscriptions that

indicate renovation by this prince.

On the southeastern side of the complex is an area associated with the Sed festival, which ceremonially demonstrates the pharaoh's ability to rule. On the west side of the rectangular courtyard there are thirteen chapels, built in two different designs. The Seh-netjer (God's Shadow) type has a flat roof and semicircular elevations on the edges. At the base of the roof there is an imitation of protruding palm leaves. The Per-wer type has a round roof and columns designed as pilasters on the facade. Some of the chapels have false doors. On the east side of the courtyard there are twelve more chapels, although they are smaller. All chapels are designed as mock architecture. This indicates that they were not intended for actual use as part of Sed festivals, but rather for otherworldly use as part of the ruler's cult, which was intended to enable the dead ruler to celebrate Sed festivals for all eternity. Some of the chapels have been completely reconstructed.

The rectangular building located between the Sed Festival chapels and the south courtyard, which Lauer gave the working name Temple “T”, was apparently a temple that was included in the Sed Festival ceremony. Similar to other buildings in the pyramid complex, the usual mud brick construction was transferred to stone, which was a functional architecture. The temple consisted of an entrance colonnade, an antechamber, three inner courtyards and a hall with a square floor plan. Entrances to the temple were in the east and south. The ceiling, made of limestone slabs, was supported by columns.

The mortuary temple was located on the north side of the pyramid and

formed the central element for the ruler's cult. It had an east-west

orientation and was entered through an entrance in the southeast, which

was built in stone to imitate an opened wooden door. A portico made of

double columns led from the entrance to the inner area. The floor of the

temple was slightly elevated compared to the surrounding structures.

Numerous corridors, galleries and rooms make up the interior of the

temple. The interpretation and reconstruction of the various components

of the temple is difficult because its structure differs significantly

from all later mortuary temples.

The temple structure contained

two courtyards located east and west of the center of the temple. The

access stairs to the pyramid were also located in the western courtyard.

The mortuary temple was probably originally planned further south,

but had to be moved further north as the pyramid was enlarged several

times. The mortuary temple was originally planned to be significantly

larger and the northern areas were filled in as a solid mass, presumably

in order to quickly complete the temple after the death of the pharaoh.

The Serdab (Arabic: cellar) is a small chamber east of the mortuary

temple on the north side of the pyramid. The entire serdab is tilted

inwards by 17°, just like the building blocks of the pyramid. In the

Serdab Chamber was a life-size statue of Djoser, made of limestone,

depicting the ruler sitting sternly on the throne. There are two holes

in the north side of the chamber that were intended to allow the statue

to view the rituals performed in the courtyard. The chamber's tilt can

also be interpreted as an alignment with the circumpolar stars.

The original of the statue is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, while

a replica is installed in the Serdab. During the reconstruction, a side

stone of the serdab was replaced with a pane to allow visitors to look

inside.

Statue fragments similar to the Serdab statue were found

in the mortuary temple area, which may indicate a possible second

Serdab.

The south house was an elongated building, which probably (according

to Lauer) replicated a wooden frame building with a rounded flat roof.

The roof was supported by several rows of four stone half-columns,

painted red and black to simulate cedar trunks. The interior of the

building was filled with solid masonry, similar to the Sed Festival

chapels. An L-shaped chapel was located in the pavilion. Visitor

graffiti from the 18th and 19th dynasties has been preserved on the

walls, including the first mention of the name “Djoser”. Firth found the

remains of charred papyri during excavations.

The north house was

constructed similarly to the south pavilion, but had a smaller courtyard

and an altar and niches were missing. Instead there is a shaft to an

underground gallery.

The significance of the pavilions has not

yet been fully clarified. According to Lauer, the buildings represent

Upper and Lower Egypt in the form of symbolic administrative buildings

in which the pharaoh's Ka was supposed to receive the respective

subjects.

Based on the papyri finds, Firth assumed that in later

times the administration of the pyramid complex was housed in the south

pavilion. On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that the pavilions

were intentionally buried after completion to provide them directly for

the pharaoh's afterlife.

The remains of the north and south

pavilions were mistaken by the Lepsius expedition for the ruins of

secondary pyramids and were therefore incorrectly included in the

Lepsius pyramid list under the names Lepsius XXXIII (33) and Lepsius

XXXIV (34).

The western massifs with their underlying galleries are among the

most enigmatic structures in the pyramid complex. The westernmost of the

three massifs runs the entire length of the complex, while the other two

are shorter. The superstructure may have been built from rubble from the

pyramid building and does not contain any corridors. The structures must

have been completed before the final construction phase of the pyramid,

as it sits on the eastern massif in the west.

The substructure of

the western galleries consists of long corridors and over 400 chambers.

The purpose of these chambers is not yet clear. The general character

makes them appear to be camp magazines, but Lauer sees them as possible

graves of Djoser's servants, who were sacrificed to serve the pharaoh in

the afterlife. However, the practice of sacrificing servants at the

pharaoh's burial was abandoned as early as the 1st Dynasty.

Rainer Stadelmann suspects that these could be the remains of an earlier

grave from the Early Dynastic period (possibly the grave of

Chasechemui), although there are no known usurpations of royal graves in

the Old Kingdom.

According to Andrzej Ćwiek, the western massifs

represent the very first construction phase of the Djoser tomb. After

that, the tomb was initially intended to be a gallery tomb with a huge,

elongated mastaba-like structure in the style of the two tombs of the

2nd Dynasty that can be found south of the Djoser complex. This theory

connects the complex with the earlier designs and avoids Stadelmann's

usurpation problem.

The northern area of the complex has not yet been systematically

examined, but individual excavations have already produced some

elements.

There is a structure called the North Altar on the

northern perimeter wall. It is a high plateau that is accessible via a

step ramp. On the plateau there is a depression measuring 8 m × 8 m and

a few centimeters deep. The function of this element is still

controversial. Stadelmann interprets it as a sun temple. The depression

could then indicate the position of an obelisk. However, neither an

obelisk nor fragments of one have been found.

Another magazine

gallery extends eastward from the northwest corner of the surrounding

wall. These probably represented granaries, as they have round filling

openings in the ceiling. In the northern galleries, seal impressions

from Djoser as well as those from Chasechemui were found, which connects

them to the problematic classification of the western galleries.

In the north courtyard there are also some stair graves that are older

than the Djoser complex and come from an earlier necropolis that was

built over by the Djoser complex.

In later times, various additional shafts and galleries were dug -

mainly by grave robbers.

Already at the end of the Old Kingdom, a

grave robber passage was dug from the transverse gallery in the entrance

area to the galleries around the burial chamber in order to loot them.

Other grave robber tunnels date back to Roman times.

Particularly

striking is a gallery under the pyramid that was dug in the 26th dynasty

(Saïte period), the entrance of which is in the south courtyard west of

the altar and which leads to the central shaft of the tomb. This gallery

was supported with reused columns. With the help of this gallery, the

central shaft, which was filled with rubble, was emptied and access to

the burial chamber was made possible for the purpose of grave robbery.

Wooden beams used to support the central shaft are still on site today.

Recent research using ground-penetrating radar by a Latvian team led

by Bruno Deslandes also revealed evidence of at least three additional

tunnels driven from outside the eastern boundary wall to the eleven

eastern galleries, as well as another tunnel connecting the southern

chambers of the main tomb with the south tomb.

Although no second tomb complex was built based on the Djoser pyramid

model, various elements still influenced the style. The exact

development is no longer traceable today because the two subsequent

projects - the Sechemchet pyramid and the Chaba pyramid - were not

completed. In particular, the Sechemchet complex shows a close

relationship with the Djoser complex, which is due to the fact that

Imhotep was also the master builder of this complex.

The Djoser

pyramid is therefore the only royal tomb completed and preserved as a

layered pyramid. A number of small provincial pyramids built as

cenotaphs were also layer pyramids. The next completed royal pyramid,

the Meidum Pyramid of Snefru, was apparently initially completed as a

layered pyramid and in a later construction phase was converted into a

pyramid with an external cladding with a constant inclination. All other

royal pyramids were basically built as real pyramids. However, later two

queen pyramids of the Menkaure pyramid were also built in the form of

step pyramids. Likewise, the later pyramids of the 4th to 6th dynasties

were constructed in steps with an external cladding (e.g. Mykerinos

pyramid, Sahure pyramid).

It is noteworthy that initially the

importance and size of the pyramid increases significantly while the

complex is reduced. The external galleries of the Djoser complex were

incorporated into the substructure of the subsequent pyramids in an

increasingly reduced form. The substructure has also been significantly

simplified. Elements such as the Heb Sed courtyard or the north and

south pavilions disappeared completely from subsequent pyramid

complexes, although the Sed festival motif remained present in the form

of relief depictions in the mortuary temple.

The mortuary temple

is an element that can be found in all later pyramids. The importance of

this temple increased significantly, especially from the 5th Dynasty

onwards. However, the design of the later mortuary temples differs from

that of Djoser.