Location: Khoms, Murqub District

Best known: hometown of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus

Best time to visit: Oct- June

Leptis Magna, also spelled Lepcis Magna, is one of the most significant and well-preserved archaeological sites of the ancient Roman world, located on the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Libya, near the town of Al-Khums, approximately 130 kilometers east of Tripoli. Founded by Phoenicians around the 10th century BCE, it evolved into a major Roman city under the empire, renowned for its monumental architecture, urban planning, and cultural synthesis of Punic, Roman, and North African influences.

Leptis Magna’s history spans over a millennium, reflecting its

strategic importance as a trading hub and its adaptation to successive

cultural and political shifts:

Phoenician Origins (c. 10th–7th

century BCE):

Leptis was established by Phoenician settlers from Tyre

or Sidon, part of a network of coastal trading posts in North Africa.

Its name likely derives from the Punic term Lpqy, meaning "outlet" or

"port," reflecting its role as a harbor city. The natural harbor, formed

by the Wadi Lebda, facilitated trade in goods like olive oil, grain, and

exotic animals (e.g., elephants and lions) from the African interior.

Carthaginian Period (6th–2nd century BCE):

Under Carthage’s

dominance, Leptis grew as a key port in the Punic Mediterranean trade

network. It was one of the three major Punic cities in the region (the

"Tripolis," alongside Oea and Sabratha). The city prospered through

agriculture, particularly olive production, and trade with sub-Saharan

Africa.

Roman Annexation (146 BCE–1st century CE):

After

Rome’s victory in the Third Punic War (146 BCE), Leptis came under Roman

influence as part of the province of Africa Proconsularis. Initially a

free city (civitas libera), it retained some autonomy. By the 1st

century CE, under Emperor Augustus, Leptis was fully integrated into the

Roman Empire, gaining status as a municipium (a self-governing city with

Roman citizenship for its elites).

Golden Age (1st–3rd century

CE):

Leptis reached its zenith under the Roman Empire, particularly

during the reign of Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 CE), a native son of

the city. Born into a wealthy Punic family, Severus elevated Leptis to a

colonia (a city with full Roman rights) and funded lavish building

projects, transforming it into one of the empire’s most splendid cities.

Its wealth stemmed from grain, olive oil, and trade, making it a vital

supplier to Rome.

Decline (4th–7th century CE):

The city’s

fortunes waned with the broader decline of the Western Roman Empire.

Vandal invasions in the 5th century disrupted trade, and siltation of

the harbor reduced its economic viability. By the 6th century, under

Byzantine rule, Leptis was a smaller, fortified settlement. Arab

conquests in the 7th century led to its near abandonment, as populations

shifted inland. Sand dunes buried much of the city, preserving it until

modern excavations.

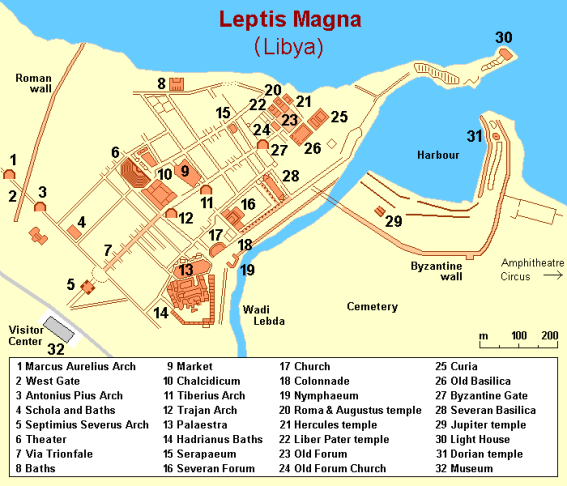

Leptis Magna’s urban plan reflects Roman engineering and aesthetic

ideals, with a grid-like layout adapted to the coastal terrain.

Covering approximately 400 hectares at its peak, the city featured a

mix of Punic, Hellenistic, and Roman architectural styles. Below are

its major features:

The Harbor and Wadi Lebda:

The

artificial harbor, expanded under Nero and Septimius Severus, was a

marvel of Roman engineering. Two long moles (breakwaters) protected

the port, with a lighthouse (reminiscent of Alexandria’s Pharos)

guiding ships. The Wadi Lebda, a seasonal river, was channeled to

prevent flooding and siltation, with dams and aqueducts managing

water flow.

The Severan Arch (c. 203 CE):

A monumental

tetrapylon (four-sided arch) dedicated to Septimius Severus, this

triumphal arch stood at a major crossroads. Adorned with intricate

reliefs depicting the emperor’s victories, family, and civic life,

it exemplifies imperial propaganda. The arch’s white marble and

elaborate carvings remain well-preserved.

The Severan

Basilica (c. 216 CE):

One of the largest basilicas in the Roman

world, this structure was completed under Severus’s son, Caracalla.

Measuring 92 meters long, it served as a law court and public

meeting space. Its two apses, adorned with colossal columns and

reliefs of mythological scenes (e.g., Hercules and Bacchus), reflect

Severan grandeur. Under Byzantine rule, it was converted into a

church.

The Forum (Old and Severan):

Old Forum (1st

century BCE–1st century CE): Located near the harbor, this earlier

civic center included temples to Roman and Punic deities (e.g.,

Liber Pater and Hercules) and a market. It reflects the city’s

pre-Severan prosperity.

Severan Forum (c. 200 CE): A vast new

complex funded by Severus, this 100x60-meter plaza was surrounded by

a colonnaded portico. At its center stood a temple to the Severan

family, deified after Severus’s death. The forum’s scale and

decoration rivaled those of Rome.

The Theater (c. 1st–2nd

century CE):

Built into a hillside, the theater could seat

5,000–6,000 spectators. Its three-tiered cavea (seating area),

orchestra, and scaenae frons (stage backdrop) are exceptionally

preserved. Statues of gods and emperors adorned the stage, and

inscriptions honor local benefactors. The theater hosted plays,

gladiatorial contests, and public events.

The Amphitheater

and Circus (c. 56 CE):

Located outside the city center, the

amphitheater (seating ~16,000) hosted gladiatorial games and animal

hunts. Nearby, the circus (450 meters long) was used for chariot

races. Both reflect Leptis’s wealth and Roman cultural priorities.

Baths of Hadrian (c. 127 CE):

Among the finest Roman bath

complexes in North Africa, these public baths featured hot and cold

rooms, mosaics, and a sophisticated heating system (hypocaust).

Renovated under Severus, they included a large outdoor palaestra

(exercise area) and pools.

The Market (Macellum, c. 8 BCE):

A central commercial hub, the market consisted of two circular

pavilions surrounded by shops. Standardized measures (e.g., for

grain and oil) carved into stone ensured fair trade. Its Hellenistic

design recalls earlier Punic influences.

Residential and

Industrial Areas:

Elite villas with peristyle courtyards and

mosaics coexisted with modest homes and workshops. Olive presses and

warehouses near the harbor underscore the city’s agricultural and

commercial economy.

Defensive Walls and Gates:

While

Leptis relied on its harbor for defense, Byzantine-era walls (6th

century) enclosed a smaller area, reflecting the city’s contraction.

The Arch of Trajan (c. 109 CE) and other gates marked major entry

points.

Leptis Magna was a melting pot of Punic, Roman, and North African

cultures, evident in its art, religion, and society:

Cultural

Synthesis:

The city’s elite spoke Punic and Latin, and inscriptions

show a blend of Roman and local names. Temples to Punic gods (e.g.,

Shadrapa and Milk’ashtart) stood alongside those to Jupiter and Venus.

Mosaics and sculptures combined Roman realism with African motifs, such

as lions and elephants.

Economic Powerhouse:

Leptis was a

linchpin in Rome’s grain and olive oil supply chain, with vast estates

(latifundia) in the hinterland producing surplus for export. Its trade

networks extended to sub-Saharan Africa (ivory, gold, slaves) and the

eastern Mediterranean (spices, luxury goods). The city’s merchants and

landowners amassed immense wealth, funding public works.

Septimius Severus’s Legacy:

As the first African-born Roman emperor,

Severus’s patronage elevated Leptis’s status. His family’s rise from

local aristocracy to imperial power highlights the city’s social

mobility and integration into the Roman system.

Leptis’s decline was gradual but irreversible. By the 7th century, sand encroachment and economic collapse left the city largely abandoned. Its ruins, buried under dunes, were spared the looting and destruction faced by other ancient sites. European travelers in the 17th–18th centuries noted the visible remains, but systematic excavations began under Italian colonial rule (1911–1942). Archaeologists like Giacomo Caputo uncovered the Severan monuments, theater, and baths, revealing the city’s scale.

Today, Leptis Magna is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (designated in

1982), recognized for its outstanding universal value. Its

well-preserved structures, including the Severan Arch, basilica, and

theater, make it a premier example of Roman urbanism. However,

challenges threaten its preservation:

Environmental Threats:

Coastal erosion, sand encroachment, and flooding from the Wadi Lebda

endanger structures.

Political Instability: Libya’s civil conflict

since 2011 has limited conservation efforts and tourism. Looting and

vandalism have occurred, though the site remains relatively intact.

Conservation Efforts: International organizations, including UNESCO and

the Libyan Department of Antiquities, work to stabilize structures and

train local conservators, but funding and access remain limited.

For those able to visit (security permitting), Leptis offers a breathtaking journey into the Roman past. The site is accessible from Al-Khums, with guided tours highlighting the forum, theater, and baths. The adjacent Leptis Magna Museum houses artifacts, including mosaics, statues, and inscriptions. Visitors are struck by the city’s scale, the intricacy of its carvings, and its serene coastal setting.