Interesting facts about the Tower of Babel

Location: Babylon, Iraq

Built: about 2nd millennia BC.

Purpose: religious

Height: 91 meters

The Tower of Babel is one of the most iconic stories from the Bible, symbolizing human ambition, divine intervention, and the origins of linguistic diversity. While the biblical narrative presents it as a cautionary tale of hubris, historical and archaeological evidence points to a real structure in ancient Mesopotamia: the Etemenanki ziggurat in Babylon, located in modern-day Iraq. This massive stepped temple tower, dedicated to the god Marduk, is widely considered the inspiration for the biblical account. Etemenanki, whose Sumerian name translates to "House of the foundation of heaven on earth," served as a religious and cultural centerpiece in one of the ancient world's greatest cities.

In the Book of Genesis (11:1-9), the Tower of Babel is described as

a monumental project undertaken by humanity shortly after the Great

Flood. At this time, "the whole earth had one language and the same

words," and people settled in the land of Shinar (ancient

Mesopotamia, encompassing parts of modern Iraq). Motivated by a

desire to "make a name for ourselves" and avoid being scattered,

they decided to build a city and a tower "with its top in the

heavens." The materials mentioned—baked bricks and bitumen as

mortar—align with Mesopotamian construction techniques, adding a

layer of historical plausibility to the story.

God, observing

their unity and ambition, intervened by confusing their language,

making communication impossible and causing the people to scatter

across the earth. This etiological myth explains the diversity of

languages and the name "Babel," derived from the Hebrew word balal

meaning "to confuse." Interestingly, the Babylonian name for the

city, Babilu, means "Gate of God" in Akkadian, showing a linguistic

play between the biblical interpretation and the original term. The

story also ties into themes of empire-building, possibly reflecting

Israelite views on Babylonian hubris during their exile in the 6th

century BCE.

Scholars debate the tower's symbolic role: some see

it as a critique of ziggurat worship, where these structures were

viewed as artificial mountains linking earth to the divine realm,

while others interpret it as a metaphor for the fragmentation of

human society.

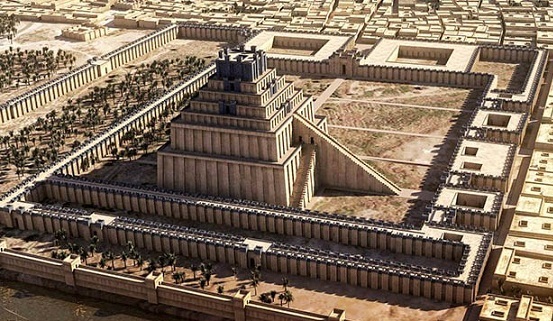

Etemenanki was no ordinary building; it was a engineering marvel of

the ancient world. Originally constructed during the Old Babylonian

period (around Hammurabi's era), it was repeatedly damaged by

invasions and rebuilt. The most famous version was commissioned by

Nabopolassar (r. 626–605 BCE) and completed by his son

Nebuchadnezzar II, who boasted in inscriptions of using "baked

bricks" and "bitumen" to create a structure that "reached the

heavens."

The ziggurat had a square base measuring approximately

91 meters (300 feet) on each side, rising in seven tiers to a height

of about 91 meters—comparable to a 30-story modern building. Each

level was slightly smaller than the one below, creating a stepped

pyramid. The exterior was clad in glazed blue bricks, symbolizing

the heavens, with ramps or a grand staircase providing access to the

summit shrine dedicated to Marduk. Inside, it likely housed temples,

storerooms, and priestly quarters. Construction required an

estimated 17 million bricks, involving massive labor forces—echoing

the biblical theme of collective human effort.

A key artifact is

the "Tower of Babylon Stele," discovered in Babylon and depicting

Nebuchadnezzar II standing before a detailed relief of the ziggurat,

confirming its multi-tiered design and religious purpose.

Reconstructions based on ancient descriptions show a towering,

imposing structure that dominated the Babylonian skyline.

Archaeological digs provide concrete evidence linking Etemenanki to

the Tower of Babel. The site was first excavated by Robert Koldewey

in the early 20th century, revealing the ziggurat's foundations amid

Babylon's ruins. Today, only a watery pit and scattered bricks

remain, as the structure was dismantled—possibly by Xerxes I in 482

BCE after a rebellion, or later by Alexander the Great, who planned

to rebuild it but died before completion.

Inscriptions from

Nebuchadnezzar describe the tower's purpose as a bridge between

heaven and earth, aligning with the biblical narrative. No direct

proof of language confusion exists, but the story may reflect the

multilingual nature of Babylonian society, with Sumerian, Akkadian,

and other tongues in use. Modern Iraq preserves these ruins as part

of the UNESCO-listed Babylon site, though damage from wars, looting,

and Saddam Hussein's partial reconstructions (using modern bricks)

has complicated preservation efforts.

Biblical Origins and Mythological Context

The Tower of Babel is

primarily known from the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible

(Genesis 11:1–9), where it serves as an etiological myth explaining

the diversity of human languages and the scattering of peoples

across the Earth. According to the narrative, shortly after the

Great Flood, humanity was united by a single language and migrated

eastward to the land of Shinar (often interpreted as the plain of

southern Mesopotamia, corresponding to modern-day Iraq). There, they

decided to build a city and a massive tower "with its top in the

heavens" to make a name for themselves and prevent their dispersal.

The materials used were brick baked in fire (rather than stone) and

bitumen (a tar-like substance) for mortar, reflecting construction

techniques common in ancient Mesopotamia where stone was scarce.

God (Yahweh in the text) observed this act of hubris, which

challenged divine authority by attempting to bridge the gap between

earth and heaven. In response, God confounded their language,

creating multiple tongues so that the people could no longer

understand one another, leading to confusion (the Hebrew word balal,

meaning "to mix" or "confuse," is a play on the name "Babel"). The

construction halted, the people scattered across the world, and the

unfinished city was named Babel. This story is traditionally dated

to around the 21st century BCE in biblical chronologies, associated

with the post-flood era and figures like Nimrod, a "mighty hunter

before the Lord" mentioned in Genesis 10:8–10. Extra-biblical

traditions, such as those in the works of the 1st-century CE Jewish

historian Flavius Josephus, portray Nimrod as a tyrannical king who

instigated the tower's construction as an act of defiance against

God, fearing another flood.

Parallels to this tale exist in

earlier Mesopotamian literature, suggesting the biblical account may

draw from Sumerian and Akkadian myths. For instance, the Sumerian

epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (dated to around the 21st–20th

century BCE) describes the legendary king Enmerkar building a

massive ziggurat in Eridu and petitioning the god Enki to disrupt

the unified speech of humanity across regions like Sumer, Akkad, and

the Martu lands—mirroring the theme of linguistic confusion as

divine intervention. Similarly, the Eridu Genesis, a Sumerian flood

myth, references a time when all humanity spoke one language before

divine disruption. These stories highlight themes of human ambition

clashing with divine order, common in ancient Near Eastern

cosmology.

Historical and Archaeological Association with

Etemenanki

While the biblical Tower of Babel is mythological,

scholars widely identify it with Etemenanki (Sumerian for

"House/Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth"), a real

ziggurat in the ancient city of Babylon, located in modern-day Babil

Governorate, Iraq, about 85 kilometers (53 miles) south of Baghdad.

Babylon, known as Bāb-ilim or Bāb-ili in Akkadian (meaning "Gate of

God"), was a major center of Mesopotamian civilization, and its

name's similarity to the Hebrew "Babel" likely influenced the

biblical wordplay. The association is strengthened by the biblical

setting in Shinar, which corresponds to Babylonia, and the

historical context of the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE), when

Jewish captives in Babylon would have encountered such monumental

structures, inspiring the Genesis narrative.

Etemenanki was part

of the Esagila temple complex dedicated to Marduk, the chief god of

Babylon, symbolizing the axis mundi—the cosmic link between earth,

heaven, and the underworld in Babylonian mythology. Ziggurats,

stepped pyramid-like towers, were ubiquitous in Mesopotamia from the

3rd millennium BCE, serving as elevated platforms for temples rather

than habitable structures. They represented sacred mountains,

allowing priests to ascend closer to the gods for rituals.

Etemenanki's purpose aligned with this: it was a "stairway to

heaven" for divine encounters, including astronomical observations

by Chaldean priests, who used it to track celestial events like

eclipses and planetary movements as early as the 17th century BCE.

Babylonian astronomy from this site contributed to advanced

knowledge, such as stellar catalogs by the 8th century BCE and

eclipse predictions by the 7th century BCE.

The structure was

immense: a seven-terraced ziggurat rising 91 meters (about 300 feet)

high, with a square base measuring approximately 91 x 91 meters

(exact archaeological measurements: 91.48 x 91.66 meters). Each

terrace decreased in size, accessed by large southern staircases and

gates, creating the illusion of a continuous stairway to the sky.

The topmost level housed a temple with opulent rooms for Marduk and

his consort Sarpanitum, as well as chambers for other deities like

Nabu (god of wisdom), Tashmetu, Ea (god of water), Nusku (god of

light), Anu (sky god), and Enlil (wind god). These included beds,

thrones, and altars for rituals, possibly including sacred marriages

(hieros gamos) between gods and selected humans, though Greek

historian Herodotus's 5th-century BCE account of a woman spending

the night with the god is likely exaggerated or misinterpreted. The

roof may have served for stargazing, and the entire edifice was

roofed with cedar from Lebanon, adorned with blue-glazed bricks

symbolizing the heavens.

Archaeological evidence for Etemenanki

comes from excavations in the early 20th century by German

archaeologist Robert Koldewey, who uncovered the foundations in a

marshy area of Babylon's ruins. Today, only overgrown channels and a

waterlogged depression mark the site, as the structure was built on

unstable ground prone to erosion. Key artifacts include the "Tower

of Babylon Stele," discovered in Babylon and depicting the ziggurat

alongside King Nebuchadnezzar II, confirming its form and royal

patronage. Cuneiform tablets, such as one from the Louvre dated to

229 BCE (a copy of an older text), describe its idealized design,

while Neo-Assyrian inscriptions from kings like Sennacherib

reference similar motifs of divine confusion and scattering.

Key Figures, Timeline, and Fate

Early Origins (Pre-18th Century

BCE): Ziggurats existed in Mesopotamian cities like Uruk and Nippur

during the time of Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BCE), but Etemenanki's

initial construction is unconfirmed, possibly dating back over 1,000

years before its mentions.

Assyrian Period (8th–7th Century BCE):

Assyrian king Sennacherib claimed to destroy Babylon and its

ziggurat in 689 BCE during a revolt, though this is debated as

ancient armies couldn't fully demolish such massive brickworks. His

successor Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BCE) began reconstruction,

continued amid conflicts involving Aššurbanipal (r. 668–627 BCE).

Neo-Babylonian Empire (7th–6th Century BCE): Under Nabopolassar (r.

626–605 BCE), founder of the empire, rebuilding intensified. His son

Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BCE), famous for the Hanging Gardens

and the conquest of Jerusalem, completed the upper temple, boasting

in inscriptions that it "reached heaven." The process spanned over a

century, involving millions of baked bricks.

Persian and

Hellenistic Periods (6th–4th Century BCE): Persian king Xerxes I (r.

486–465 BCE) allegedly damaged it during revolts, but cuneiform

evidence shows the cult continued. By Alexander the Great's conquest

in 331 BCE, neglect had caused disrepair. Alexander ordered 10,000

men to clear rubble for rebuilding, but his death in 323 BCE halted

plans. Seleucid ruler Antiochus I Soter (r. 281–261 BCE) used

elephants to demolish the remains, per chronicles.

Later History:

The site fell into obscurity, with Esagila surviving into the 1st

century BCE. Rediscovered in the 19th century, excavations in 1913

confirmed its scale.

Beyond its physical form, the Tower of Babel has profoundly

influenced art, literature, and philosophy. Pieter Bruegel the

Elder's famous painting depicts it as a spiraling colossus, while

linguists see it as an early myth on language origins—modern

estimates suggest over 7,000 languages worldwide, perhaps nodding to

the "scattering." In Mesopotamian lore, similar tales exist, like

the Epic of Gilgamesh, where gods interact via lofty structures.

The story also critiques imperialism: Babylon's fall in 539 BCE to

Cyrus the Great may symbolize divine judgment, paralleling the

biblical theme. Today, it inspires discussions on unity versus

diversity in a globalized world.

The remnants of Etemenanki lie in the Babil Governorate of Iraq, amid the larger ruins of Babylon. Visitors can see the foundation pit, often flooded due to the high water table, alongside reconstructed elements like the Ishtar Gate (now in Berlin's Pergamon Museum). The site faces threats from climate change, urban development, and past military use (e.g., as a base during the 2003 Iraq War). UNESCO recognition in 2019 aims to protect it, but access is limited due to security concerns. For a sense of its grandeur, digital reconstructions and museum models offer vivid insights.