The Via Dolorosa, Latin for "Way of Suffering" or "Sorrowful

Way," is a historic processional route in the Old City of Jerusalem

that commemorates the path Jesus Christ is believed to have taken

while carrying his cross to the site of his crucifixion at Golgotha.

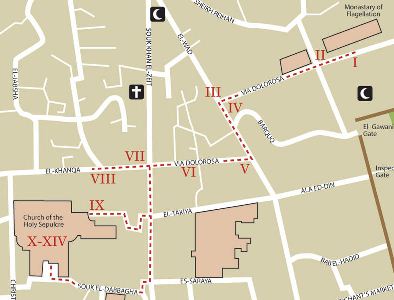

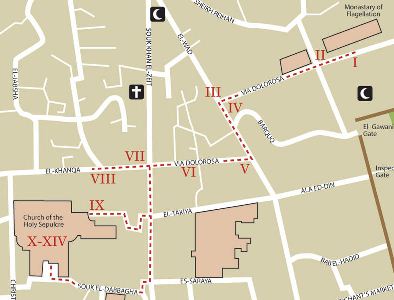

Spanning approximately 600 meters (about 2,000 feet), the route

winds through the Muslim and Christian Quarters, starting near the

former site of the Antonia Fortress (close to the Lions' Gate) and

ending at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which encompasses the

traditional locations of the crucifixion and burial. This path is

not a single straight street but a series of interconnected alleys

and roads, marked by 14 Stations of the Cross—nine along the outdoor

route and five inside the church. It holds profound religious

significance for Christians worldwide, serving as a focal point for

pilgrimage, meditation on the Passion of Christ, and devotional

processions.

The route symbolizes the final hours of Jesus' life,

drawing from New Testament accounts and later Christian traditions.

It is bustling with daily life—vendors, shops, and

crowds—contrasting its solemn purpose, yet this vibrancy enhances

the immersive experience for visitors. Annually, especially during

Holy Week, thousands of pilgrims walk the path, often in processions

led by Franciscan friars, who have overseen Christian holy sites in

Jerusalem since the 14th century.

Location: Old City of Jerusalem, primarily within the Muslim and

Christian Quarters

Length: Approx. 600 meters (0.4 miles)

Stations of the Cross: 14 traditional "Stations" commemorating events on

Jesus’ journey to Calvary

Religious Significance: Central to

Christian pilgrimage and liturgical devotion, especially during Holy

Week and Good Friday

Beginning about 200–300 meters west of the Lions' Gate in the Muslim

Quarter, near the Umariya Elementary School (site of the ancient Antonia

Fortress), the path heads westward along Lions' Gate Street (also called

Via Dolorosa Street). It navigates through narrow, winding alleys,

incorporating segments of ancient Roman roads like the Decumanus

Maximus, a main east-west thoroughfare from Hadrian's Aelia Capitolina

(built after 135 AD). The route passes bustling souks (markets) on

streets such as Al-Wad and Khan es-Zeit, ascending slightly uphill with

stairs in places, before turning south toward the Christian Quarter and

entering the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Archaeological remnants

along the way include the Ecce Homo Arch (a triple archway from

Hadrian's era, partially preserved in the Church of Ecce Homo), ancient

pavements, and sections of the original city wall. The path's elevation

changes reflect Jerusalem's layered history, with modern streets often

built atop ruins from Roman, Byzantine, and Crusader periods.

Processions today, including weekly Friday walks led by Franciscans,

follow this route, sometimes with re-enactments featuring actors

portraying Jesus and Roman soldiers.

The Via Dolorosa has been a route of Christian pilgrimage since at

least the 4th century, when Christianity became the official religion of

the Roman Empire. The path commemorates the Passion of Christ as

described in the Gospels, and later embellished through Christian

tradition, including apocryphal and devotional texts like the

14th-century Meditations on the Life of Christ.

Over time, the

exact route has shifted, influenced by theological emphasis, urban

development, and control of Jerusalem by different empires. The current

route was formalized by the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land in the

18th century.

The 14 Stations of the Cross

The Via Dolorosa is

marked by 14 "Stations", each commemorating a moment from Jesus' journey

with the Cross. The first nine are along the street route; the final

five are within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Stations I–IX:

Along the Street

Jesus is Condemned to Death – Near the site of the

Antonia Fortress (inside a Muslim school now).

Jesus Takes Up His

Cross – Adjacent to Station I.

Jesus Falls the First Time – On

El-Wad Road.

Jesus Meets His Mother – Commemorates a traditional

meeting with the Virgin Mary.

Simon of Cyrene Helps Jesus Carry

the Cross – A stone embedded in the wall is believed to mark the spot.

Veronica Wipes Jesus’ Face – Based on later Christian tradition; the

cloth allegedly retained Jesus’ image.

Jesus Falls the Second

Time – At the entrance to the Souq Khan al-Zeit.

Jesus Meets the

Women of Jerusalem – Commemorates Luke 23:28.

Jesus Falls the

Third Time – At the entrance to the courtyard of the Holy Sepulchre.

Stations X–XIV: Inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Jesus is

Stripped of His Garments

Jesus is Nailed to the Cross

Jesus Dies on the Cross

Jesus is Taken Down from the Cross

Jesus is Laid in the Tomb

These events unfold within the

architectural spaces of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built on what

early Christians identified as Golgotha (Calvary) and the nearby tomb of

Jesus.

The Via Dolorosa winds through narrow, bustling streets of the Old

City, intersecting with local markets (souks), mosques, churches, and

homes. While the modern route is a devotional path rather than a precise

archaeological line, it is richly steeped in centuries of tradition.

Start Point: Near Lions’ Gate (St. Stephen’s Gate)

End Point:

Inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Languages on Signs:

Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, Greek

The Via Dolorosa's origins trace back to early Christian pilgrimage

practices in the Byzantine era (4th–7th centuries), when devotees

followed approximate paths commemorating Jesus' journey. Initially,

there were no fixed stations; a Holy Thursday procession started from

the Mount of Olives, passed through Gethsemane, entered the city via the

Lions' Gate, and followed a route similar to today's. By the 8th

century, the path shifted to the western hill, beginning at Gethsemane,

touching the House of Caiaphas on Mount Zion, and proceeding to the Holy

Sepulchre.

During the Crusader period (1095–1291 AD), the route was

associated with the Antonia Fortress as the starting point, influenced

by the belief that Pontius Pilate's Praetorium (judgment hall) was

located there. The name "Via Dolorosa" emerged in the 16th century,

inspired by European devotional practices, and the 14-station format was

standardized in the 18th–19th centuries under Franciscan influence. In

1342, an Ottoman sultan granted the Franciscans authority over key

Christian sites, solidifying their role in guiding pilgrims. Early tours

sometimes reversed the direction (from the Holy Sepulchre back to

Pilate's house), but by the early 16th century, the chronological order

from condemnation to burial became standard.

The route has evolved

amid debates over historical accuracy. Some early traditions placed the

trial at Herod's Palace near the Jaffa Gate, suggesting an alternative

western path. Archaeological findings, such as a 2009 discovery by

Shimon Gibson of a paved courtyard with a judgment platform south of the

Jaffa Gate, support this view, indicating the Praetorium might have been

there rather than at Antonia. This would imply a revised route starting

in the Armenian Quarter, passing the Tower of David, and reaching the

Holy Sepulchre—a shorter path aligning better with Gospel descriptions.

Despite this, the traditional Via Dolorosa remains the most followed,

valued more for its spiritual symbolism than precise historicity.

While spiritually vital, the route's historical precision is debated. The assumption that Pilate's trial occurred at Antonia Fortress underpins the path, but Josephus and other sources suggest judgments happened at Herod's Palace (near Jaffa Gate). Excavations reveal Roman pavements and structures supporting alternative routes, with the crucifixion site potentially just 20 meters from the trial location in a revised western path. Elements like the Lithostratos (a grooved stone slab in the Convent of the Sisters of Zion, evoking soldiers' games) and ancient arches add tangible links to the Roman era, though the city's repeated destructions (e.g., in 70 AD and 135 AD) mean modern streets sit atop older layers. Regardless, the Via Dolorosa's value lies in its role as a meditative journey rather than an exact reconstruction.

For Christians—Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, and others—the Via Dolorosa embodies the core of the Passion narrative, fostering reflection on sacrifice, redemption, and faith. It draws from Gospel events expanded by medieval texts like the Meditaciones vite Christi, emphasizing encounters like those with Mary, Simon, Veronica, and the women of Jerusalem. Pilgrims use it for prayer, often carrying crosses or joining re-enactments, linking personal devotion to Jesus' suffering. Inter-denominational sites (e.g., Armenian, Coptic, Greek chapels) highlight shared guardianship. Its enduring appeal transcends historical debates, symbolizing the "Way of the Cross" (Via Crucis) central to Lent and Holy Week observances.

The path is free and open year-round, but guided tours or maps are essential as stations can be hard to spot amid crowds. Join the Franciscan-led Friday procession at 3 PM (4 PM in summer) for a structured experience. Wear modest clothing (covered shoulders/knees, closed shoes) and comfortable footwear for the uneven terrain. The area is safe but busy; visit early to avoid peak times. Despite geopolitical tensions, pilgrims from various faiths continue to walk it, underscoring Jerusalem's multi-religious tapestry.