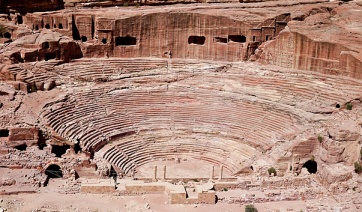

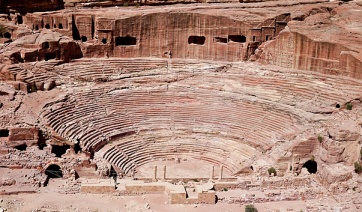

The Petra Amphitheatre, also known as the Petra Roman Theatre or Nabataean Theatre, is a remarkable rock-cut performance venue in the ancient Nabataean city of Petra, Jordan. Carved into a sandstone hillside in the 1st century CE, it lies at the heart of Petra’s main valley, near the Colonnaded Street and opposite the Royal Tombs, including the Silk Tomb, Tomb of Aneisho, and Al Khazneh. With a seating capacity of approximately 7,000–8,500, the amphitheatre is a testament to Nabataean engineering and cultural sophistication, adapted to Roman architectural standards during Petra’s peak as a trade hub. Its strategic location and well-preserved state make it a key feature of Petra’s UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Petra, located 240 kilometers south of Amman and 120 kilometers north

of Aqaba, was the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom from the 4th century

BCE to the 2nd century CE. The Nabataeans, a nomadic Arab tribe,

transformed Petra into a thriving trade hub, controlling caravan routes

for frankincense, myrrh, spices, and silk between Arabia, Egypt, and the

Mediterranean. The amphitheatre was constructed during the reign of King

Aretas IV (9 BCE–40 CE) or Malichus II (40–70 CE), likely in the early

1st century CE, based on its architectural style and Nabataean

rock-cutting techniques.

Although called a “Roman Theatre,” the

amphitheatre predates Petra’s annexation by Rome in 106 CE, which formed

the province of Arabia Petraea. Its design reflects Nabataean adaptation

of Hellenistic and early Roman theatre models, similar to those at

Jerash’s North Theatre or Pella’s odeon. The amphitheatre was carved

into a hillside, displacing several earlier Nabataean tombs, indicating

its civic importance. It served as a venue for performances, public

gatherings, and possibly religious ceremonies, aligning with Petra’s

role as a cultural and trade center.

Petra’s decline after the

3rd century CE, due to shifting trade routes and earthquakes (notably

363 CE), reduced the amphitheatre’s use. By the Byzantine period, Petra

became a Christian center, with churches like the Petra Church nearby,

mirroring the Christianization seen at Madaba’s Church of Saint George

and Mount Nebo. The amphitheatre may have been repurposed for Christian

gatherings, similar to the reuse of Lot’s Cave. Rediscovered by Johann

Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812, the amphitheatre was excavated in the 1960s

by the American Center of Research and Philip Hammond, revealing its

scale and significance. Recent studies, including 2024 surveys, continue

to explore its acoustic properties and context within Petra’s urban

landscape.

The Petra Amphitheatre is a semi-circular, rock-cut structure, carved

directly into a sandstone hillside, with a capacity of 7,000–8,500

spectators, larger than Jerash’s North Theatre (1,600–2,000) but

comparable to Jerash’s South Theatre (3,000–5,000). Its design follows

the Roman theatre model, adapted by Nabataean engineers to Petra’s

rugged terrain and aesthetic preferences. Unlike constructed theatres,

its rock-cut nature integrates seamlessly with the rose-red sandstone

cliffs, contrasting with the limestone structures of Jerash or Montreal

Castle. Below are the key architectural elements:

1. Cavea

(Seating Area)

Structure: The cavea is a semi-circular auditorium, 36

meters in diameter, carved into the hillside with 33–45 rows of seats

(sources vary), divided into three tiers: ima cavea (lower, 14 rows),

media cavea (middle, 15 rows), and summa cavea (upper, 14–16 rows).

These tiers are separated by two diazomata (horizontal walkways),

facilitating crowd movement, similar to Jerash’s North Theatre.

Seating: The seats, hewn from sandstone, are smooth and slightly curved

for comfort, with some bearing traces of wear from centuries of use.

Unlike Jerash’s North Theatre, no inscriptions for reserved seating

(e.g., for elites) are documented, though such markings may have

existed.

Vaulted Supports: The cavea’s lower tiers are supported by

vaulted substructures, a Roman technique also seen at Jerash, ensuring

stability on the steep slope. These vaults, partially intact, housed

access corridors and possibly shops, unlike the open-air setting of

Lot’s Cave’s basilica.

Orientation: The cavea faces northeast,

optimizing shade for afternoon performances in Petra’s hot climate, a

practical design shared with Pella’s odeon.

2. Orchestra

Design: The orchestra is a semi-circular performance area, approximately

12 meters in diameter, at the cavea’s base, paved with sandstone slabs.

In Roman theatres, the orchestra was often reserved for elite seating or

musicians, unlike Greek theatres where it housed a chorus. Its size is

comparable to Jerash’s North Theatre but smaller than larger Roman

venues.

Function: The orchestra likely hosted actors, musicians, or

orators, with its flat surface ensuring clear visibility and acoustics

for the audience, a feature refined by Nabataean engineers, unlike the

simpler performance spaces at Mount Nebo’s church.

3. Scaenae

(Stage and Backdrop)

Stage Area: The scaenae frons (stage backdrop)

is a constructed stone wall, partially rebuilt in the 2nd century CE

under Roman influence, measuring about 25 meters wide and 10 meters

high. Originally, it may have been rock-cut, but Roman additions

included limestone blocks and decorative elements, contrasting with Al

Khazneh’s purely rock-cut facade.

Features: The scaenae frons had

three doorways (valvae) for actor entrances, flanked by niches for

statues, possibly of deities like Dushara or emperors, similar to

Jerash’s North Theatre. Corinthian columns and a frieze, now fragmented,

adorned the backdrop, echoing the Hellenistic style of Al Khazneh’s

upper tholos.

Proscaenium: The stage platform, elevated about 1.5

meters, was likely wooden, with stone supports surviving. Drainage

channels beneath prevented flooding, a practical feature shared with

Petra’s water systems and Montreal Castle’s tunnel.

Destruction:

Earthquakes (363, 551 CE) collapsed much of the scaenae, leaving ruins

less intact than Al Khazneh’s facade but more preserved than Pella’s

odeon.

4. Access and Entrances

Parodoi: Two vaulted side

entrances (parodoi) on the north and south flanks allowed spectators to

enter the cavea and orchestra, similar to Jerash’s North Theatre. These

corridors, carved into the rock, also provided actor access to the

stage.

External Paths: External staircases, partially eroded, led to

the upper cavea tiers, ensuring efficient crowd flow, unlike the single

staircase at Lot’s Cave. The amphitheatre’s valley location, near the

Colonnaded Street, made it accessible from Petra’s civic core.

Forecourt: A small plaza in front of the scaenae, paved with sandstone,

served as a gathering space, akin to the courtyard at Madaba’s Church of

Saint George.

5. Acoustics and Design

Acoustics: The

amphitheatre’s semi-circular design and sandstone walls amplify sound,

allowing actors’ voices to reach the upper rows without modern

amplification, a feature shared with Jerash’s theatres and tested in

2024 acoustic studies at Petra. This contrasts with the open-air

settings of Mount Nebo or Lot’s Cave.

Integration with Tombs: The

amphitheatre was carved through earlier Nabataean tombs, with some tomb

facades visible in the cavea’s lower tiers, creating a unique

juxtaposition of funerary and civic spaces, unlike Pella’s distinct

necropolis.

6. Comparative Elements

Nabataean-Roman Blend: The

rock-cut cavea is Nabataean, while the constructed scaenae reflects

Roman influence, less ornate than Al Khazneh’s Hellenistic facade or the

Tomb of Aneisho’s merlons but more functional than the Silk Tomb’s

minimal design.

Cultural Context: The amphitheatre’s civic role

contrasts with the religious focus of Jerash’s Temple of Zeus or Mount

Nebo’s church, but its performance function aligns with Pella’s odeon

and Madaba’s cultural heritage.

The Petra Amphitheatre was a cultural and civic hub, serving multiple

roles in Nabataean and Roman Petra:

Theatrical Performances: The

amphitheatre hosted plays, including Greek tragedies, Roman comedies

(e.g., Plautus), mime, and pantomime, popular in the Hellenistic-Roman

world. Musicians and poets likely performed, similar to Jerash’s North

Theatre, entertaining diverse audiences of traders, locals, and elites.

Public Gatherings: It may have served as a venue for civic assemblies,

political speeches, or judicial proceedings, akin to the bouleuterion

function of Jerash’s North Theatre or Pella’s civic complex. Nabataean

kings or Roman officials could address the city here.

Religious and

Ceremonial Events: Festivals honoring deities like Dushara or Al-Uzza,

or imperial celebrations under Roman rule, may have included

performances, paralleling rituals at Jerash’s Temple of Zeus or Mount

Nebo’s church. The amphitheatre’s proximity to the Royal Tombs suggests

possible funerary commemorations, like those at the Silk Tomb or Tomb of

Aneisho.

Social Hub: As a central gathering place, it fostered

community interaction, with merchants, pilgrims, and residents mingling,

similar to the social vibrancy of Jerash’s Colonnaded Street or Madaba’s

Church of Saint George plaza.

Byzantine Reuse: In the 4th–6th

centuries CE, the amphitheatre may have hosted Christian gatherings, as

seen in the repurposed Urn Tomb nearby or Lot’s Cave’s basilica, though

evidence is sparse.

Daily life involved performances scheduled for

cooler afternoons, maintenance by Nabataean or Roman caretakers, and the

valley’s trade-driven bustle. Spectators from Petra’s 20,000–30,000

residents, plus caravan visitors, filled the cavea, with elites possibly

occupying the ima cavea, mirroring social hierarchies.

The Petra Amphitheatre is well-preserved, benefiting from Petra’s

arid climate and sandstone durability, though it faces natural and human

challenges:

Current State: The cavea’s 33–45 rows are largely

intact, with smooth seats and visible diazomata, though some upper tiers

are eroded. The orchestra and parodoi remain functional, but the scaenae

frons is fragmented, with collapsed columns and niches, less preserved

than Al Khazneh’s facade but more intact than Pella’s odeon. The

sandstone’s rose-red hues, subtler than the Silk Tomb’s striations,

enhance its aesthetic.

Preservation Efforts: Managed by the Petra

Development and Tourism Region Authority (PDTRA) and UNESCO, the

amphitheatre undergoes conservation within Petra’s site-wide efforts.

Stabilization of the hillside prevents rockfalls, drainage channels

divert flash floods (e.g., 1963, 1996 incidents), and barriers limit

visitor climbing on seats, unlike Lot’s Cave’s exposed mosaics. The

1960s excavation by Philip Hammond cleared debris, with 2024 surveys

using acoustic modeling to study its design.

Challenges: Flash floods

threaten the valley floor, though the amphitheatre’s elevated position

mitigates risks compared to the Siq. Sandstone weathering from wind and

temperature shifts erodes carvings, similar to the Tomb of Aneisho’s

facade. Over-tourism (1 million visitors annually pre-COVID) strains the

site, but crowd management helps.

Archaeological Work: The 1960s

excavation revealed the theatre’s layout, with recent studies focusing

on its acoustic properties and tomb displacement. Unlike the 2024 Al

Khazneh find (12 skeletons), the amphitheatre has yielded few artifacts,

but its context informs Nabataean urbanism, paralleling Pella’s ongoing

digs.

Tripadvisor reviews (2025) praise the amphitheatre’s

“impressive” scale and valley views but note its scaenae ruins require

guides to contextualize, unlike Al Khazneh’s instant impact.

The Petra Amphitheatre encapsulates Nabataean and Roman cultural

achievements:

Nabataean Engineering: Its rock-cut cavea, carved

through tombs, showcases Nabataean mastery, rivaling Al Khazneh’s facade

or the water systems at Lot’s Cave’s cistern. The adaptation of Roman

design highlights Nabataean syncretism, unlike Jerash’s purely

Greco-Roman North Theatre.

Cultural Hub: As a performance venue, it

reflects Petra’s cosmopolitanism, hosting diverse audiences, similar to

Pella’s odeon or Madaba’s artistic heritage. Its civic role parallels

Jerash’s North Theatre’s potential bouleuterion function.

Trade

Context: Petra’s trade wealth funded the amphitheatre, akin to the Silk

Tomb’s elite patronage or Montreal Castle’s taxation. Its valley

location welcomed caravan visitors, enhancing Petra’s prestige.

Biblical and Regional Ties: Petra’s Edom/Moab connections link it to

Lot’s Cave and Mount Nebo. The Nabataeans’ Arab heritage, revered in

Islamic tradition, aligns with Lot’s Cave’s interfaith appeal, unlike

Montreal Castle’s Crusader-Mamluk focus.

Byzantine Transition:

Possible Christian reuse mirrors the Urn Tomb’s cathedral conversion or

Mount Nebo’s church, contrasting with Jerash’s pagan-to-Christian shift.

Touristic Appeal: As part of Petra, a New Seven Wonder, the amphitheatre

draws millions, though less iconic than Al Khazneh. Its accessibility

contrasts with Pella’s obscurity or Lot’s Cave’s remoteness.

Archaeological Value: The amphitheatre informs Nabataean urbanism,

complementing Pella’s multi-period ruins and Madaba’s mosaic map. Its

tomb displacement offers insights into civic priorities, unlike the

funerary focus of the Tomb of Aneisho.

The Petra Amphitheatre is a central stop in Petra’s Archaeological

Park, accessible via the main valley path. Recent web sources and

visitor insights provide context:

Access: Petra is 3–4 hours from

Amman (240 km), 2 hours from Aqaba, or 1 hour from Wadi Rum. The

amphitheatre is a 25–30-minute walk from the entrance through the Siq,

past Al Khazneh and the Street of Facades. Entry costs 50 JOD (1 day) or

is included in the Jordan Pass (70–80 JOD). Open 6 AM–6 PM (summer) or 4

PM (winter).

Experience: Viewing the amphitheatre takes 15–30

minutes, part of a 4–8-hour Petra itinerary with Al Khazneh, Royal Tombs

(Silk, Aneisho), and Colonnaded Street. Its valley setting offers views

of the Royal Tombs, best photographed in late morning or afternoon.

Guides (20–50 JOD for half-day) or audio guides (10 JOD) detail its

history, as signage is minimal. Visitors can climb lower cavea rows

(upper tiers restricted), unlike Al Khazneh’s closed interior. Camels or

donkeys (5–10 JOD) aid mobility nearby.

Challenges: Petra’s heat

(30–40°C in summer) and uneven terrain require water, sunscreen, and

sturdy shoes, less strenuous than Lot’s Cave’s climb or Montreal

Castle’s ascent. Crowds peak near Al Khazneh (9 AM–noon), but the

amphitheatre is quieter, unlike Madaba’s Church of Saint George. Vendors

can be persistent, manageable with firm refusals. Accessibility is

limited for mobility-impaired visitors, unlike Mount Nebo’s pathways.

Nearby Sites: Within Petra, visit Al Khazneh, Royal Tombs, Ad Deir, or

Petra Church. Day trips include Madaba (190 km), Mount Nebo (200 km),

Lot’s Cave (140 km), or Montreal Castle (100 km). Jerash (240 km) or

Pella (270 km) suit a Decapolis tour.

An X post from June 2025

describes the amphitheatre as a “hidden gem” in Petra’s valley, urging

visitors to imagine ancient performances, reinforcing its appeal.