Location: Wadi Musa

Phone: +962 3 215 6020

Open:

Oct-Apr: 6:30 am - 5 pm

May-Sep: 6am - 5:30 pm

These are ticket sales hours. Some people stay long after sunset.

Petra, known as the “Rose City” for its vibrant sandstone cliffs, is an ancient city in southern Jordan, carved into the desert canyons by the Nabataean Kingdom. Located approximately 240 kilometers south of Amman and 120 kilometers north of Aqaba, Petra is one of the world’s most iconic archaeological sites, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (1985), and a New Seven Wonder (2007). As the Nabataean capital from the 4th century BCE to the 2nd century CE, it thrived as a trade hub controlling caravan routes for frankincense, myrrh, spices, and silk. Its rock-cut architecture, including the Treasury (Al Khazneh), Silk Tomb, and Tomb of Aneisho, blends Nabataean, Hellenistic, and Roman influences, creating a unique cultural legacy. Petra’s biblical ties to Edom and Moab, its decline after the 3rd century CE, and its rediscovery in 1812 by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt cement its historical significance.

Petra’s history spans millennia, rooted in its strategic location in

the Wadi Araba, a rift valley connecting the Dead Sea to the Red

Sea. The site’s natural springs and defensible canyons attracted

early settlers, with evidence of Edomite presence by the 8th century

BCE. The Nabataeans, a nomadic Arab tribe, settled Petra around the

4th century BCE, transforming it into a trade hub under kings like

Aretas III (87–62 BCE) and Aretas IV (9 BCE–40 CE).

Nabataean

Period (4th Century BCE–106 CE): Petra reached its zenith in the 1st

century BCE–CE, controlling caravan routes from Arabia to the

Mediterranean. Monumental tombs like Al Khazneh (1st century

BCE–CE), Silk Tomb, and Tomb of Aneisho (50–76 CE) reflect the

wealth of Nabataean elites. The city’s infrastructure, including

water channels and markets, supported a population of 20,000–30,000.

Petra’s trade dominance rivaled that of Pella and Jerash in the

Decapolis.

Roman Period (106–324 CE): Rome annexed Petra in 106

CE, forming the province of Arabia Petraea. Roman influences appear

in structures like the Colonnaded Street and Roman Theatre, akin to

Jerash’s urban planning. Petra remained a trade center but began

declining as maritime routes via the Red Sea grew.

Byzantine

Period (324–636 CE): Petra became a Christian center, with churches

like the Petra Church and the repurposed Urn Tomb (converted to a

cathedral in 447 CE). This mirrors the Christianization seen at

Lot’s Cave and Madaba’s Church of Saint George. Earthquakes in 363

and 551 CE damaged the city, reducing its prominence.

Islamic and

Medieval Periods (636–1516 CE): After the Muslim conquest, Petra

faded into obscurity, though Umayyad and Abbasid settlers used its

ruins. Crusaders built outposts like Montreal Castle nearby in the

12th century, but Petra was largely abandoned. Bedouin tribes,

particularly the Bdoul, inhabited its caves into the 20th century.

Modern Rediscovery: Johann Ludwig Burckhardt’s 1812 rediscovery

sparked global interest. Excavations by scholars like Gustaf Dalman,

Rudolf-Ernst Brünnow, and recent teams (e.g., American Center of

Research, 2024) have uncovered tombs, temples, and artifacts,

cementing Petra’s archaeological value.

Petra’s biblical

associations with Edom and Moab (e.g., Sela in Isaiah 16:1) and its

Nabataean-Arab heritage, revered in Islamic tradition, link it to

sites like Lot’s Cave and Mount Nebo.

Petra’s architecture is defined by its rock-cut monuments, carved

into sandstone cliffs, and constructed buildings, blending

Nabataean, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine styles. Spanning 264

square kilometers, the site includes over 800 registered monuments,

with tombs, temples, theatres, and civic structures. Below are key

architectural features:

1. Rock-Cut Monuments

Al Khazneh (The

Treasury): A 39.1-meter-high facade (1st century BCE–CE) at the

Siq’s exit, likely a tomb for Aretas IV, with Corinthian columns,

Hellenistic reliefs (Isis, Amazons), and a tholos. The 2024

excavation uncovered a subterranean tomb with 12 skeletons,

confirming its funerary role. Its grandeur overshadows the Silk

Tomb’s colorful simplicity and Aneisho’s Hegra-type design.

Silk Tomb: A Royal Tomb with a 10.8-meter-wide facade, named for its

vibrant red, yellow, and blue striations, featuring a crowstep

motif. Its minimal carvings contrast with Al Khazneh’s opulence but

share Nabataean funerary purpose.

Tomb Aneisho (BD 813): A

20-meter-high facade on Jabal al-Khubtha (50–76 CE), with merlons,

pilasters, and a pediment, built for Uneishu, a minister under Queen

Shaqilath II. Its 11 loculi and inscription distinguish it from the Silk Tomb’s anonymity.

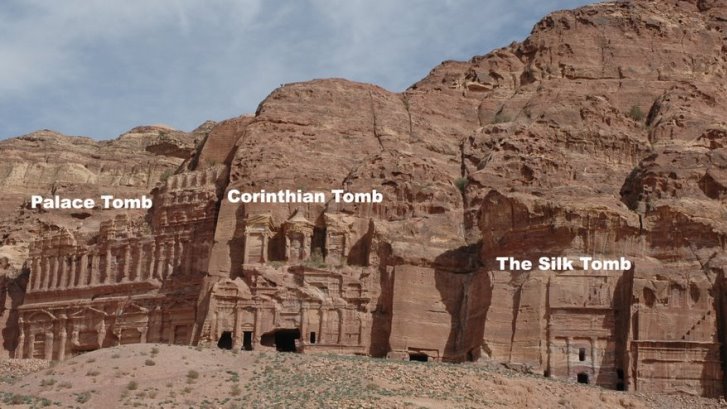

Royal Tombs:

On the eastern cliff, including the Urn Tomb (converted to a church

in 447 CE), Corinthian Tomb, and Palace Tomb, these showcase

Nabataean wealth, akin to Jerash’s Temple of Zeus. The Urn Tomb’s

large chamber and barrel-vaulted ceiling contrast with Aneisho’s

simplicity.

Al Deir Monastery: A 47-meter-high facade (1st

century CE) high in the mountains, similar to Al Khazneh but with

simpler Nabataean capitals. Likely a temple or tomb, its remote

location mirrors Lot’s Cave’s isolation.

Tombs and Necropolis:

Over 600 tombs dot Petra, from elaborate facades to simple caves,

like the Street of Facades and Obelisk Tomb. These parallel Pella’s

necropolis but emphasize family mausoleums.

Obelisk Tomb

Corinthian Tomb

Palace Tomb

Urn Tomb

2. Constructed Structures

Colonnaded Street: A Roman-era (2nd

century CE) street with limestone columns, shops, and a nymphaeum,

resembling Jerash’s Colonnaded Street but smaller. It connects the

city center to the Qasr al-Bint temple.

Roman Theatre: Carved

into a hillside (1st century CE), seating 7,000–8,500, it hosted

performances like Jerash’s North Theatre. Its proximity to the Royal

Tombs mirrors Pella’s odeon placement.

Qasr al-Bint: A

freestanding temple (1st century BCE–CE) dedicated to Dushara or

Al-Uzza, with a monumental staircase and stucco decoration. Unlike

rock-cut tombs, it uses ashlar masonry, akin to Montreal Castle’s

construction.

Temples and Sanctuaries: The Great Temple (1st

century BCE–CE), with its theatrical layout, and the Temple of the

Winged Lions highlight Nabataean worship, paralleling Jerash’s

Temple of Zeus but with Arabian motifs.

Byzantine Churches: The

Petra Church (5th century CE) features mosaics of animals and

seasons, similar to Madaba’s Church of Saint George and Mount Nebo’s

baptistery. The Blue Chapel and Ridge Church add to Petra’s

Christian layer.

Byzantine

Church

Petra Amphitheatre

Bedouin Market

Djinn Blocks

High Place of Sacrifice

3. Infrastructure

Water Systems:

Nabataean hydraulic engineering included 200 cisterns, dams, and 50

kilometers of clay pipes, channeling flash floods and springs to

sustain the city. This ingenuity rivals Montreal Castle’s secret

water tunnel and Lot’s Cave’s cistern.

Siq and Wadis: The

1.2-kilometer Siq, a narrow canyon, serves as Petra’s main entrance,

revealing Al Khazneh dramatically. Wadi Musa and other canyons

facilitated trade and defense, unlike Pella’s open valley.

Caravan Stations: Structures like Al Wu’ayra and Al Habis, Nabataean

and Crusader outposts, protected trade routes, similar to Montreal

Castle’s strategic role.

4. Architectural Style

Nabataean

Core: Rock-cut facades with crowsteps (Silk Tomb), merlons

(Aneisho), or Hellenistic elements (Al Khazneh) blend Arabian,

Mesopotamian, and Greek influences, distinct from Jerash’s

Greco-Roman columns or Madaba’s Byzantine mosaics.

Hellenistic

and Roman Influences: Corinthian columns (Al Khazneh, Great Temple)

and pediments reflect Hellenistic Alexandria, while the Colonnaded

Street and theatre show Roman urbanism, akin to Pella’s civic

complex.

Byzantine Additions: Church mosaics and repurposed tombs

mark Christianization, paralleling Lot’s Cave’s basilica and Mount

Nebo’s church.

Petra’s multifaceted roles as a trade hub, religious center, and

necropolis shaped its vibrant life:

Trade Hub: Controlling

caravan routes, Petra amassed wealth through taxes on goods like

frankincense and silk, akin to Jerash’s Colonnaded Street markets or

Montreal Castle’s trade oversight. The Colonnaded Street and Qasr

al-Bint area hosted merchants and traders.

Religious Center:

Temples to Dushara and Al-Uzza, plus high places like Jabal Haroun

(Aaron’s Tomb), served Nabataean worship, similar to Jerash’s Temple

of Zeus. Byzantine churches later hosted Christian liturgies, like

Madaba’s Church of Saint George.

Funerary Role: Tombs like Al

Khazneh, Silk Tomb, and Aneisho were elite mausoleums, with rituals

outside facades, paralleling Pella’s necropolis. The 2024 Al Khazneh

excavation (12 skeletons) confirms burial practices.

Civic and

Cultural Life: The Roman Theatre hosted performances, like Jerash’s

North Theatre, while the Great Temple and Qasr al-Bint were

administrative and ceremonial hubs, akin to Pella’s palaces.

Daily Life: Petra’s 20,000–30,000 residents lived in stone houses,

caves, and tented suburbs, engaging in trade, agriculture (olives,

grapes), and crafts. Water systems ensured resilience in the desert,

unlike Lot’s Cave’s monastic austerity.

By the Byzantine period,

Petra’s population dwindled, with churches replacing temples.

Bedouin reuse of tombs into the 20th century, similar to Lot’s Cave,

added a living cultural layer.

Petra’s arid climate and sandstone durability preserve its

monuments, but natural and human threats persist:

Current

State: Al Khazneh, Silk Tomb, and Aneisho’s facades are intact, with

vivid colors and carvings. The Colonnaded Street, theatre, and

churches show partial ruin, like Pella’s skeletal remains.

Earthquakes (363, 551 CE) and looting damaged some structures, less

severely than Montreal Castle’s plundered stones.

Preservation

Efforts: Managed by the Petra Development and Tourism Region

Authority (PDTRA) and UNESCO, Petra undergoes extensive

conservation. Dams divert flash floods (e.g., 1963, 1996 incidents),

cliff faces are stabilized, and visitor access is restricted (e.g.,

Al Khazneh’s interior closed since 2024). Ground-penetrating radar

and LiDAR, used in the 2024 Al Khazneh excavation, map subsurface

features, protecting sites, unlike Lot’s Cave’s exposed mosaics.

Challenges: Flash floods threaten low-lying areas like the Siq,

though less for elevated tombs like Aneisho. Sandstone weathering

erodes details, similar to the Silk Tomb’s striations. Over-tourism

(1 million visitors annually pre-COVID) strains infrastructure,

unlike Pella’s quieter site, mitigated by crowd management and

barriers.

Archaeological Work: Excavations by Zayadine, the

American Center of Research, and others uncover tombs, churches, and

artifacts. The 2024 Al Khazneh find (12 skeletons, ceramics) joins

discoveries like the Petra Church mosaics (1990s), paralleling

Pella’s ongoing Bronze Age digs.

Tripadvisor reviews (2025)

praise Petra’s “otherworldly” beauty but note heat, crowds, and

persistent vendors, recommending multi-day visits.

Petra’s significance spans cultural, historical, and global

dimensions:

Nabataean Legacy: Its rock-cut architecture,

blending Arabian, Hellenistic, and Roman styles, showcases Nabataean

ingenuity, distinct from Jerash’s Greco-Roman grandeur or Madaba’s

Byzantine mosaics. Al Khazneh’s reliefs and Aneisho’s inscription

highlight cultural syncretism.

Trade and Power: Petra’s caravan

control fueled wealth, paralleling Pella’s Decapolis markets or

Montreal Castle’s taxation. Its monuments symbolize elite power,

like Jerash’s Temple of Zeus.

Biblical Context: Ties to Edom/Moab

(e.g., Sela in Isaiah 16:1) link Petra to Lot’s Cave and Mount Nebo.

The Nabataeans’ Arab heritage, revered in Islamic tradition, aligns

with Lot’s Cave’s interfaith appeal.

Byzantine Christianity:

Churches like the Petra Church reflect Christianization, similar to

Madaba’s Church of Saint George and Mount Nebo’s basilica,

contrasting with Montreal Castle’s Crusader-Mamluk shift.

Global

Icon: Petra’s fame, amplified by Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

and its New Seven Wonder status, surpasses Pella’s obscurity or

Lot’s Cave’s niche appeal. Its UNESCO status (1985) underscores

universal value.

Archaeological Value: Excavations reveal

Nabataean society, complementing Pella’s multi-period ruins and

Madaba’s mosaic map. The 2024 Al Khazneh find adds to burial

knowledge, unlike Jerash’s civic focus.

Petra is Jordan’s top attraction, drawing millions, with robust

infrastructure but challenges from over-tourism. Recent web sources

and visitor insights include:

Access: Petra is 3–4 hours from

Amman (240 km), 2 hours from Aqaba, or 1 hour from Wadi Rum. Entry

costs 50 JOD (1 day), 55 JOD (2 days), or is included in the Jordan

Pass (70–80 JOD). Open 6 AM–6 PM (summer) or 4 PM (winter). The

Visitor Center offers guides (20–50 JOD), audio guides (10 JOD), and

maps.

Experience: A 1-day visit covers the Siq, Al Khazneh, Royal

Tombs (Silk, Aneisho), and Colonnaded Street (4–6 hours, 8 km walk).

Two days include Ad Deir and Jabal Haroun (12–20 km). Sunrise (6–8

AM) avoids crowds; sunset enhances colors. “Petra by Night” (8:30

PM, 17 JOD) illuminates the Siq and Al Khazneh with candles. Horses,

camels, or donkeys (5–20 JOD) aid mobility, unlike Lot’s Cave’s

steep climb.

Challenges: Heat (30–40°C in summer) and uneven

terrain require water, sunscreen, and sturdy shoes, less strenuous

than Montreal Castle’s ascent. Crowds peak at Al Khazneh (9

AM–noon), unlike Aneisho’s quiet hilltop. Vendors and animal

handlers can be pushy, similar to Madaba’s Church of Saint George

but manageable with firm refusals. Accessibility is limited for

mobility-impaired visitors, unlike Mount Nebo’s pathways.

Nearby

Sites: Within Petra, visit Al Khazneh, Royal Tombs, Ad Deir, and

Petra Church. Day trips include Madaba (190 km), Mount Nebo (200

km), Lot’s Cave (140 km), or Montreal Castle (100 km). Jerash (240

km) or Pella (270 km) suit a Decapolis tour.

An X post from June

2025 describes Petra as a “timeless marvel,” urging early visits for

Al Khazneh’s serenity, reinforcing its allure.