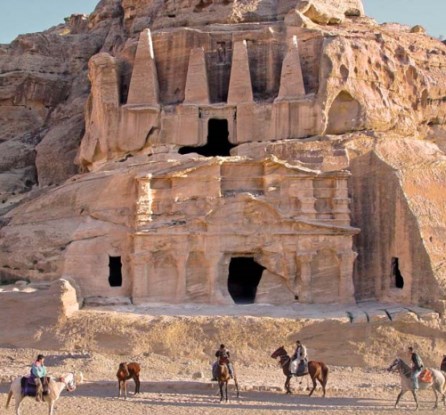

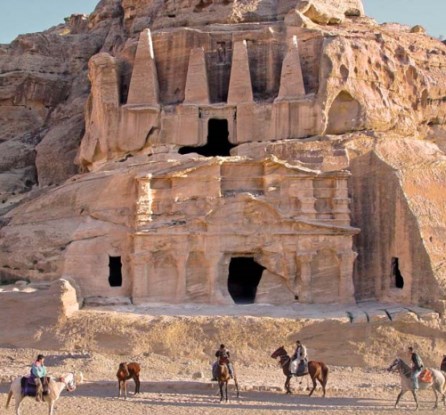

The Obelisk Tomb is one of the most distinctive and well-preserved funerary monuments in Petra, Jordan, a UNESCO World Heritage Site celebrated for its rock-cut architecture and historical significance as the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom. Located in the Bab as-Siq area, near the entrance to the Siq—the narrow canyon leading to the iconic Treasury (Al-Khazneh)—the Obelisk Tomb is a striking example of Nabataean architectural ingenuity and cultural synthesis. Its unique combination of a lower tomb facade and an upper banquet hall (triclinium), along with its prominent obelisks, makes it a key point of interest for understanding Nabataean funerary practices, artistic influences, and urban planning.

The Obelisk Tomb is situated in the Bab as-Siq, a wide valley that

forms the main approach to Petra from the visitor center,

approximately 400–500 meters from the entrance and directly across

from the famous Djinn Blocks. Positioned on the southern side of the

path, the tomb is carved into a vertical sandstone cliff, making it

highly visible to visitors as they approach the Siq. Its strategic

placement suggests it was intended to impress travelers and traders

entering the city, reflecting Petra’s role as a thriving trade hub

along ancient incense and spice routes.

Petra, often called

the "Rose City" for its reddish sandstone, was established as the

Nabataean capital by the 4th century BC and reached its zenith

between the 2nd century BC and the 2nd century AD. The Obelisk Tomb,

dated to the 1st century BC, represents a mature phase of Nabataean

monumental architecture, blending local traditions with influences

from Hellenistic, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian cultures.

The Obelisk Tomb is a two-part monument, comprising a lower tomb

facade and an upper banquet hall, both carved directly into the

sandstone cliff. Its most distinctive features are the four tall

obelisks crowning the structure, which give the tomb its name. The

monument’s design is both functional and symbolic, combining

practical burial spaces with elements of Nabataean religious and

cultural expression.

Lower Tomb (Facade and Burial Chamber)

Facade: The lower part of the monument features a rock-cut facade

approximately 10 meters wide and 6 meters high, designed in a

simplified classical style. The facade includes a central doorway

flanked by two smaller niches or windows, with a stepped pediment

above. The pediment, resembling a broken triangular gable, is a

hallmark of Nabataean architecture, seen in later structures like

the Treasury. The facade’s relatively plain design, compared to more

ornate tombs, suggests an earlier construction date within Petra’s

architectural timeline.

Burial Chamber: The central doorway leads

to a single, rectangular burial chamber, roughly 5 meters deep and 4

meters wide, with a low ceiling. The chamber contains loculi (niches

for burials) carved into the walls, typical of Nabataean tombs. The

interior is unadorned, emphasizing its utilitarian purpose as a

resting place for the deceased, likely an elite family or individual

given the tomb’s prominence.

Upper Banquet Hall (Triclinium)

Above the tomb, a separate rock-cut chamber, known as the Bab as-Siq

Triclinium, is carved into the cliff. This rectangular room,

approximately 8 meters wide and 5 meters deep, features benches

along three walls, characteristic of a triclinium—a dining or

banquet hall used for commemorative feasts honoring the dead.

The

triclinium’s facade is simpler than the tomb’s, with a plain

rectangular doorway and minimal decoration. Its interior is also

unadorned, but its size and layout suggest it accommodated

gatherings of family or community members for rituals, a common

Nabataean practice tied to ancestor veneration.

Obelisks

The four obelisks, each about 7 meters tall, are carved from the

cliff face above the triclinium, standing in a row and dominating

the monument’s silhouette. These freestanding, tapering pillars are

square-based and slightly pointed at the top, resembling Egyptian

obelisks but adapted to Nabataean aesthetics. Unlike true Egyptian

obelisks, which were monolithic and freestanding, these are integral

to the cliff, carved in relief.

The obelisks are evenly spaced

and aligned, creating a balanced, monumental appearance. Their

surfaces are smooth, with no inscriptions or carvings, emphasizing

their symbolic rather than decorative role.

The Obelisk Tomb is carved from Petra’s soft, reddish sandstone, which allowed for precise cutting but is prone to erosion. The monument’s clean lines and symmetrical design reflect the Nabataeans’ advanced stone-working skills, likely using chisels, hammers, and scaffolding to shape the cliff. The integration of the tomb and triclinium into a single cliff face demonstrates sophisticated planning, as the Nabataeans had to account for the rock’s natural contours while ensuring structural stability.

The Obelisk Tomb is dated to the 1st century BC, based on its

architectural style and comparisons with other Petra monuments. This

places it in the later phase of Nabataean development, after the

Djinn Blocks (2nd–3rd century BC) but before the Treasury (1st

century AD). Its design reflects a period of cultural synthesis, as

the Nabataeans, originally nomadic Arabs, absorbed influences from

neighboring civilizations while maintaining their distinct identity.

Funerary Practices

The tomb’s burial chamber and associated

triclinium highlight the Nabataeans’ complex funerary traditions.

Tombs in Petra were typically reserved for the elite, and the

Obelisk Tomb’s prominent location suggests it belonged to a

high-status individual or family, possibly royalty or wealthy

merchants. The triclinium indicates that commemorative feasts were

held to honor the deceased, a practice common in Nabataean and

broader Hellenistic cultures. These rituals likely involved

offerings, music, and communal dining, reinforcing social bonds and

ancestral memory.

Symbolism of the Obelisks

The four

obelisks are the tomb’s most enigmatic feature, and their purpose

remains debated. Several interpretations exist:

Nefesh

Symbols: In Nabataean culture, obelisks often represented a nefesh,

a memorial or soul of the deceased, symbolizing their enduring

presence. The four obelisks may commemorate multiple individuals

buried in the tomb or emphasize the importance of the primary

occupant.

Egyptian Influence: The obelisks’ shape recalls

Egyptian monuments, which symbolized divine power and connection to

the sun god Ra. The Nabataeans, through trade with Ptolemaic Egypt,

likely adopted this form, adapting it to their own religious

context, possibly linking the deceased to Dushara, the chief

Nabataean god.

Mesopotamian Influence: Some scholars suggest the

obelisks resemble Mesopotamian stelae, which marked sacred or

commemorative sites. This reflects Petra’s role as a cultural

crossroads.

Architectural Innovation: The obelisks may simply be

an aesthetic choice, designed to make the tomb stand out in the

crowded necropolis of Bab as-Siq.

Cultural Synthesis

The

Obelisk Tomb’s design blends Nabataean, Hellenistic, and Egyptian

elements. The stepped pediment and classical facade echo Hellenistic

architecture, while the obelisks draw from Egyptian traditions. The

triclinium, meanwhile, is a distinctly Nabataean feature, rooted in

local funerary practices. This fusion underscores Petra’s

cosmopolitan nature, as the Nabataeans engaged with Greek, Egyptian,

and Persian cultures through trade and diplomacy.

Urban

Planning

The tomb’s placement in Bab as-Siq, alongside the Djinn

Blocks and other early monuments, suggests that this area served as

Petra’s primary necropolis in its formative centuries. The monuments

were likely intended to awe visitors, signaling the city’s wealth

and power. The Obelisk Tomb’s elevated position and bold obelisks

made it a focal point of this sacred landscape, guiding the

transition from the outer valley to the inner city.

Despite its prominence, the Obelisk Tomb’s exact purpose and

patronage remain speculative due to the scarcity of Nabataean

written records. Key points of discussion include:

Patronage:

No inscriptions identify the tomb’s occupants, but its size and

location suggest a royal or elite family. Some propose it belonged

to a king like Obodas I (reigned c. 96–85 BC), though this is

unconfirmed.

Obelisk Count: The four obelisks are unusual, as

most Nabataean tombs feature one or two nefesh. They may represent

multiple burials, a family group, or a symbolic number tied to

Nabataean cosmology.

Dating: The 1st century BC date is based on

stylistic comparisons, but some argue for an earlier construction

(2nd century BC) due to the tomb’s simplicity relative to later

facades.

Later Use: Like many Petra tombs, the chamber may have

been reused in Roman or Byzantine times (after Petra’s annexation in

106 AD), though no evidence confirms this.

Recent studies, such

as those in Petra: The Rose City (2018), emphasize the tomb’s role

in Petra’s early urban development and its reflection of Nabataean

cultural adaptability. Archaeological surveys continue to refine its

dating and context.

For modern visitors, the Obelisk Tomb is an early highlight of a

Petra tour, often viewed en route to the Siq. Its bold obelisks and

cliffside setting make it photogenic, though it is sometimes

overshadowed by more famous monuments like the Treasury. Guides

typically explain its dual structure and cultural significance,

encouraging visitors to appreciate its historical context.

Tourism: The tomb is easily accessible along the main path, with no

climbing required, making it suitable for all visitors. Signage

provides basic information, though detailed insights often come from

guides or resources like the Petra Visitor Centre.

Cultural

Practices: Some Bedouin vendors near the tomb share local stories,

occasionally linking the obelisks to djinn or ancient spirits,

echoing the folklore surrounding the nearby Djinn Blocks. While not

historically accurate, these tales add to the site’s mystique.

Visitor Feedback: Tripadvisor reviews praise the tomb’s striking

appearance but note its brief stopover status, as most tourists

prioritize deeper sites. Its proximity to the Djinn Blocks allows

for combined exploration, enhancing the sense of Bab as-Siq as a

necropolis.

The Obelisk Tomb’s sandstone construction makes it vulnerable to erosion, particularly from wind and rain, which have softened its edges over time. Petra’s UNESCO status has prompted conservation efforts, including monitoring and limited restoration, but the tomb’s exposed cliff face poses ongoing challenges. Tourism foot traffic, while beneficial for awareness, risks indirect damage to the surrounding area. Ongoing archaeological work aims to protect the monument while uncovering more about its context.