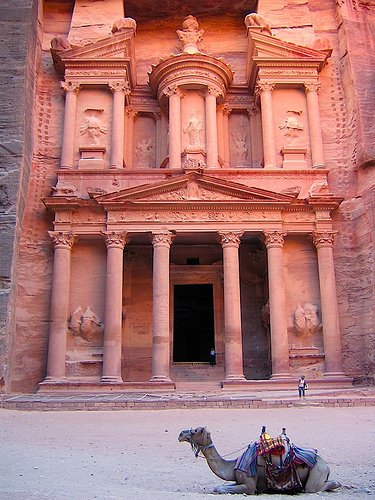

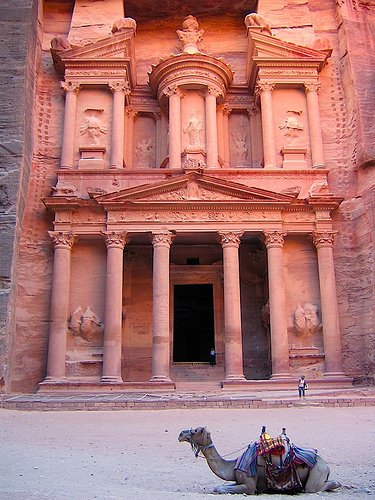

Al Khazneh, commonly known as "The Treasury," is the most iconic and celebrated monument in the ancient Nabataean city of Petra, Jordan. Carved into a towering rose-red sandstone cliff at the end of the Siq, Petra’s dramatic entrance canyon, this rock-cut tomb or temple is a masterpiece of Nabataean architecture, dating to the 1st century BCE or CE. Renowned for its intricate Hellenistic facade, Al Khazneh served as a funerary monument, possibly for King Aretas IV, though its exact function remains debated, with theories suggesting it was also a temple or ceremonial hall. Its grandeur, enhanced by its cinematic appearance in films like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), makes it Petra’s premier attraction within the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Petra, located 240 kilometers south of Amman and 120 kilometers north

of Aqaba, was the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom from the 4th century

BCE to the 2nd century CE. The Nabataeans, a nomadic Arab tribe,

transformed Petra into a thriving trade hub, controlling caravan routes

for frankincense, myrrh, spices, and silk between Arabia, Egypt, and the

Mediterranean. Al Khazneh, meaning "The Treasury" in Arabic (a Bedouin

name reflecting myths of hidden treasure), was likely constructed during

the reign of King Aretas IV (9 BCE–40 CE), Petra’s golden age, though

some scholars propose an earlier date under Aretas III (87–62 BCE) or a

later one under Malichus II (40–70 CE).

The monument’s purpose is

uncertain. Its architectural style and burial niches suggest it was a

tomb, possibly for Aretas IV, given its scale and central location.

However, its temple-like facade and lack of extensive burial chambers

have led some to hypothesize it served as a temple to a deity like

Dushara or Al-Uzza, a ceremonial hall, or a royal archive. A 2024

excavation by the American Center of Research uncovered a subterranean

tomb with 12 skeletons beneath Al Khazneh, reinforcing its funerary

role, though the occupants’ identities remain unknown.

Petra’s

annexation by Rome in 106 CE, forming the province of Arabia Petraea,

introduced Roman influences seen in Jerash’s Colonnaded Street, but Al

Khazneh is purely Nabataean, predating significant Roman impact.

Earthquakes in 363 CE and later centuries damaged Petra, and by the

Byzantine period, the city became a Christian center, with tombs like

the nearby Urn Tomb repurposed as churches, similar to Lot’s Cave’s

reuse. Rediscovered by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812, Al Khazneh has

captivated global audiences, its fame amplified by pop culture and

archaeological discoveries.

Al Khazneh is a rock-cut monument, carved top-down into a

40-meter-high sandstone cliff at the Siq’s exit, creating a theatrical

reveal for visitors. Spanning 25.3 meters wide and 39.1 meters high, its

two-story facade is one of Petra’s most elaborate, blending Nabataean,

Hellenistic, Alexandrian, and Roman architectural elements. Unlike the

simpler Silk Tomb or the Hegra-type Tomb of Aneisho, Al Khazneh’s

intricate carvings and symmetry reflect unparalleled craftsmanship.

Below are its key architectural elements:

1. Facade

Lower

Story: The lower facade features a portico with six Corinthian columns,

four freestanding and two engaged (attached to the cliff). These

columns, topped with acanthus-leaf capitals, support a pediment with a

central relief, possibly of Isis or Tyche, flanked by Amazons or

Victories. The pediment’s Hellenistic style contrasts with the Nabataean

crowstep motifs of the Silk Tomb or Aneisho’s merlons.

Upper Story:

Above a broken pediment, the upper story centers on a tholos (circular

pavilion) with a conical roof and an urn (the “treasure” of Bedouin

lore, pockmarked by bullet holes from treasure hunters). Flanking the

tholos are two half-pediments with reliefs of griffins, eagles, or

sphinxes, symbolizing protection. The tholos design echoes Alexandrian

architecture, unlike Jerash’s Greco-Roman temples.

Reliefs and

Carvings: The facade is adorned with mythological figures, including

Castor and Pollux with horses, dancing Amazons, and floral motifs

(vines, pomegranates). These reliefs suggest Nabataean syncretism,

blending Arabian, Greek, and Egyptian iconography, distinct from the

Byzantine mosaics of Madaba’s Church of Saint George.

Symmetry and

Proportion: The facade’s balanced proportions, with precise alignments

of columns and pediments, demonstrate Nabataean mastery of rock-cutting,

achieved without scaffolding by carving from the cliff top downward.

2. Interior

Main Chamber: The interior is a large, rectangular

chamber, approximately 12 x 12 meters, with smooth sandstone walls and a

flat ceiling. Three smaller chambers branch off: one at the rear and one

on each side, each with burial niches (loculi) for sarcophagi or

ossuaries, confirming its funerary role. The 2024 excavation revealed a

subterranean chamber beneath the main floor, accessed via a sealed

entrance, containing 12 skeletons, ceramics, and jewelry, suggesting

elite burials.

Simplicity: The interior is austere, lacking the

plaster or paint speculated in the Silk Tomb or the loculi-heavy design

of the Tomb of Aneisho (11 niches). This simplicity contrasts with the

facade’s opulence, emphasizing external display over internal function,

unlike Pella’s multifunctional churches.

Access: A wide, rectangular

doorway, framed by the portico, leads to the main chamber, elevated

slightly to prevent water ingress, a feature shared with other Petra

tombs.

3. Surrounding Context

Siq Entrance: Al Khazneh’s

location at the Siq’s exit, a 1.2-kilometer-long, narrow canyon, creates

a dramatic reveal, unlike the open valley settings of the Silk Tomb or

Tomb of Aneisho. The Siq’s walls, up to 80 meters high, frame the facade

like a natural stage, enhancing its impact.

Valley Context: Facing

the main valley, Al Khazneh overlooks the Street of Facades and Roman

Theatre, connecting it to Petra’s civic core, similar to Jerash’s

Colonnaded Street. Nearby tombs, like the Royal Tombs, reinforce its

funerary prominence.

Geological Setting: The cliff’s rose-red

sandstone, with subtle pink and yellow striations, is less vibrant than

the Silk Tomb’s multicolored “silk” but polished by erosion,

accentuating the carvings. Unlike Montreal Castle’s limestone

fortifications, Petra’s geology defines Al Khazneh’s aesthetic.

4. Comparative Elements

Nabataean-Hellenistic Style: The Corinthian

columns and mythological reliefs reflect Hellenistic influences, more

pronounced than the Tomb of Aneisho’s Hegra-type merlons or the Silk

Tomb’s minimal crowsteps. This syncretism contrasts with the Greco-Roman

style of Jerash’s North Theatre or the Byzantine mosaics of Mount Nebo.

Engineering Feat: Carving a 40-meter facade into a vertical cliff, using

ropes and chisels, showcases Nabataean ingenuity, rivaling the

engineering of Lot’s Cave’s rock-cut basilica or Montreal Castle’s water

tunnel.

Al Khazneh’s primary function was likely funerary, though its

temple-like facade suggests additional roles. Its context includes:

Funerary Purpose: The burial niches and 2024 subterranean tomb

confirm Al Khazneh as a mausoleum, possibly for Aretas IV or his family,

given its scale. The 12 skeletons suggest elite burials, unlike the Silk

Tomb’s anonymous occupants or Aneisho’s ministerial attribution.

Funerary rituals, including offerings and feasts, likely occurred in the

plaza outside, as no triclinium exists, unlike some Petra tombs.

Temple or Ceremonial Role: The facade’s deity reliefs (possibly Isis or

Al-Uzza) and tholos suggest a temple function, perhaps for royal

veneration or ceremonies, akin to Jerash’s Temple of Zeus. Some scholars

propose it was a royal archive or banquet hall, though evidence is

scarce.

Symbolic Status: Al Khazneh’s central location and grandeur

symbolized Nabataean power, similar to the Tomb of Aneisho’s elite

status or Pella’s civic buildings. Its reveal at the Siq’s end made it a

welcoming monument for traders and pilgrims, unlike the remote Lot’s

Cave.

Later Reuse: By the Byzantine period, tombs were repurposed as

shelters or chapels, as seen at Lot’s Cave or the Urn Tomb (converted to

a church in 447 CE). Bedouin legends of treasure hidden in the urn

reflect its enduring mystique, unlike the civic reuse of Montreal

Castle.

Daily life involved maintenance by Nabataean caretakers,

occasional funerary or ceremonial events, and the valley’s trade-driven

activity. Unlike Jerash’s bustling Colonnaded Street or Madaba’s Church

of Saint George’s liturgical life, Al Khazneh was a monumental symbol,

its activity tied to elite commemoration.

Al Khazneh is exceptionally well-preserved, thanks to Petra’s arid

climate and the Siq’s protection from wind and sun. However, natural and

human threats persist:

Current State: The facade’s carvings,

columns, and reliefs are largely intact, with minimal structural damage.

The interior chambers are stable, though looted in antiquity, as

confirmed by the 2024 excavation’s sparse artifacts. The sandstone’s

pink hues remain vivid, unlike the eroded limestone of Montreal Castle.

Preservation Efforts: Managed by the Petra Development and Tourism

Region Authority (PDTRA) and UNESCO, Al Khazneh undergoes regular

conservation. Efforts include stabilizing the cliff face, diverting

floodwater via Siq dams, and limiting visitor access to the interior

(closed to public entry since 2024 for safety). Ground-penetrating radar

and LiDAR, used in recent excavations, map subsurface features,

protecting the site, unlike Lot’s Cave’s exposed mosaics.

Challenges:

Flash floods, as in 1963 and 1996, threaten the Siq and facade, though

modern dams mitigate risks. Sandstone weathering from temperature

fluctuations erodes fine details, less severely than the Silk Tomb’s

striations. Human impact, like touching carvings, is controlled by

barriers and guides, unlike Pella’s scattered mosaic fragments.

Archaeological Work: The 2024 American Center of Research excavation,

uncovering a subterranean tomb with 12 skeletons, ceramics (jars,

lamps), and jewelry, is the most significant find since Burckhardt’s

rediscovery. Earlier surveys by Zayadine and others mapped the facade,

but interior studies remain limited due to structural concerns.

Tripadvisor reviews (2025) describe Al Khazneh as “breathtaking” and

“unforgettable,” praising its Siq reveal, but some note overcrowding and

restricted interior access, recommending early visits.

Al Khazneh embodies Petra’s Nabataean legacy and global cultural

impact:

Nabataean Artistry: The facade’s Hellenistic-Alexandrian

style, with Corinthian columns and mythological reliefs, showcases

Nabataean syncretism, more elaborate than the Silk Tomb’s natural colors

or Aneisho’s Hegra design. It rivals the craftsmanship of Madaba’s

Church of Saint George mosaics or Mount Nebo’s baptistery.

Funerary

Tradition: The tomb’s niches and subterranean burials reflect Nabataean

elite burial practices, similar to the Silk Tomb and Aneisho, but its

scale suggests royal significance, unlike Pella’s simpler necropolis.

Trade and Power: Al Khazneh’s grandeur reflects Petra’s trade wealth,

paralleling Jerash’s Colonnaded Street or Pella’s markets. Its Siq

placement welcomed caravans, akin to Montreal Castle’s trade oversight.

Biblical and Regional Context: Petra’s ties to Edom/Moab link it to

biblical narratives, like Lot’s Cave or Mount Nebo. The Nabataeans’ Arab

heritage, revered in Islamic tradition, aligns with Lot’s Cave’s

interfaith appeal.

Pop Culture Icon: Its role in Indiana Jones and

the Last Crusade and other media amplifies its fame, unlike the quieter

Tomb of Aneisho or Pella’s ruins. As a New Seven Wonder (2007) and

UNESCO site (1985), it draws millions.

Archaeological Value: The 2024

excavation provides new insights into Nabataean burials, complementing

Pella’s multi-period finds and Madaba’s mosaic map. Al Khazneh’s debated

function fuels scholarly debate, unlike the clearer roles of Jerash’s

North Theatre.

Al Khazneh is Petra’s centerpiece, accessible via the Siq within the

Petra Archaeological Park. Recent web sources and visitor insights

provide context:

Access: Petra is 3–4 hours from Amman (240 km),

2 hours from Aqaba, or 1 hour from Wadi Rum. Al Khazneh is a

15–20-minute walk from the entrance through the 1.2-kilometer Siq. Entry

costs 50 JOD (1 day) or is included in the Jordan Pass (70–80 JOD). Open

6 AM–6 PM (summer) or 4 PM (winter).

Experience: Viewing Al Khazneh

takes 30–60 minutes, part of a 4–8-hour Petra itinerary. The Siq’s

reveal is iconic, best at sunrise (6–8 AM) for soft light and fewer

crowds or midday for full illumination. Guides (20–50 JOD for half-day)

or audio guides (10 JOD) detail its history, as signage is limited. The

plaza offers photo ops, with camel or horse rides (5–10 JOD) adding

flair. The interior is closed, but the facade is fully accessible,

unlike Lot’s Cave’s restricted cave.

Challenges: Petra’s heat and

uneven terrain require water, sunscreen, and sturdy shoes, less

strenuous than Montreal Castle’s climb. Overcrowding at Al Khazneh

(especially 9 AM–noon) contrasts with the quieter Tomb of Aneisho.

Vendors and animal handlers can be persistent, though less aggressive

than at Madaba’s Church of Saint George.

Nearby Sites: Pair with the

Royal Tombs (Silk, Aneisho), Monastery, or Roman Theatre in Petra.

Madaba (190 km), Mount Nebo (200 km), Lot’s Cave (140 km), or Montreal

Castle (100 km) are day trips. Jerash (240 km) or Pella (270 km) suit a

Decapolis tour.

An X post from 2024 calls Al Khazneh a “must-see

wonder,” praising its “otherworldly” facade, reinforcing its global

allure.