The Byzantine Church in Petra, also known as the Petra Church, is a significant archaeological site within the ancient city of Petra, Jordan, offering a window into the city’s Christian era during the 5th and 6th centuries CE. Discovered in 1990 by archaeologist Kenneth W. Russell and excavated primarily by the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) between 1992 and 2002, this church is a prime example of monumental Byzantine architecture and a testament to the thriving Christian community in Petra during late antiquity.

Petra, originally the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom, was a major

trading hub due to its strategic location along incense and spice trade

routes. After the Roman annexation in 106 CE, Petra became part of the

province of Arabia Petraea. By the 4th century CE, following Emperor

Constantine’s legalization of Christianity in 313 CE, Petra saw a

growing Christian presence, though it remained predominantly pagan. The

city came under Byzantine control in the 4th and 5th centuries, and

several churches were constructed, reflecting the spread of

Christianity.

The Byzantine Church, likely dedicated to the

Virgin Mary, was constructed in the second half of the 5th century CE

(around 450 CE) and served as a major cathedral, possibly the seat of

the bishop of Petra. The church was built over earlier Nabataean and

Roman structures, indicating a layering of cultural and religious

traditions. It remained in use until the early 7th century, when it was

destroyed by a fire, possibly exacerbated by earthquakes, and was

subsequently abandoned. The discovery of 152 carbonized papyrus scrolls

(known as the Petra Papyri) in 1993 provides invaluable insight into the

social, economic, and legal life of Petra’s inhabitants during the 6th

century, under Byzantine emperors Justinian, Justin II, and Tiberius II.

The church is part of a cluster of three Byzantine churches on a

hillside overlooking Petra’s city center, alongside the Ridge Church (or

Red Church, possibly the oldest, dating to the 3rd or 4th century) and

the Blue Chapel (named for its blue Egyptian granite columns). This

concentration of churches highlights the significance of Christianity in

Petra, even as the city’s economic importance declined after the 363 CE

earthquake and shifts in trade routes.

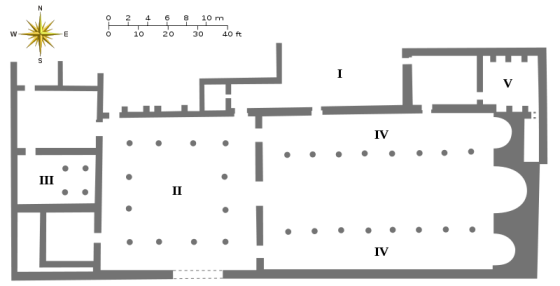

The Byzantine Church is a three-aisled basilica, measuring

approximately 26 meters by 15 meters (85 feet by 49 feet), with a

total area of about 400 square meters. Its layout and design are

characteristic of Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture, with

adaptations to the local environment and materials. Key

architectural features include:

Tripartite Basilica Layout:

The church consists of a central nave flanked by two smaller side

aisles, separated by rows of columns. The nave is paved with opus

sectile (cut stone) flooring, while the aisles are adorned with

intricate mosaics. Three apses (semicircular recesses) are located

at the eastern end, with the central apse likely housing the altar.

Three corresponding entrances (portals) at the western end provided

access to the church.

Construction Phases: Scholars distinguish

two main phases of construction:

Early Phase (c. 450 CE): The

original church had a single apse and an entrance porch. The Mosaic

of the Seasons in the southern aisle dates to this period.

Late

Phase (c. 500–550 CE): The church was remodeled to include two

additional side apses, a two-story atrium connecting the cathedral

to the baptismal complex, and additional mosaics in the northern

aisle and eastern end of the southern aisle. The nave was repaved,

and features such as chancel screens, a pulpit, and wall mosaics

were added.

Baptistery: A cruciform-shaped baptismal font,

surrounded by four columns that likely supported a dome, is located

in a side room. This baptistery underscores the church’s role in

religious ceremonies, including baptisms, which were central to

early Christian practice.

Atrium and Additional Structures: The

6th-century atrium linked the main church to the baptismal complex,

creating a unified religious complex. Side rooms, including a

storage room where the Petra Papyri were found, indicate the

church’s multifunctional role in community life.

Materials and

Hybridism: The church incorporates recycled materials from earlier

Nabataean and Roman structures, a common practice in Petra. The

architecture blends Nabataean rock-cut elements with Roman and

Hellenistic influences, reflecting a hybrid cultural identity. Local

sandstone was used for construction, and some columns and capitals

feature Nabataean horned designs.

Protective Shelter: Today, a

modern canopy covers the church to protect its delicate mosaics and

ruins from environmental damage, providing shade for visitors and

preserving the site’s integrity.

The Byzantine Church is renowned for its well-preserved figurative

floor mosaics, covering approximately 70 square meters in the side

aisles. These mosaics, created in the 5th and 6th centuries, are among

the finest in the region and reflect the artistic traditions of the

Byzantine world, with influences from the Gaza school and Hellenistic

and Roman iconography. Key features of the mosaics include:

Southern Aisle (Mosaic of the Seasons): The southern aisle is dominated

by personifications of the four seasons, identified by Greek

inscriptions. The mosaics are arranged in three columns within a

guilloche (interlaced) border:

The central column features human

figures, including the seasons and seven other figures identified by

Greek inscriptions, possibly representing virtues or deities.

The

outer columns depict animals, birds, and plants, symbolizing the

abundance of God’s creation.

Circular medallions, rectangular panels,

and conch-shaped designs add to the complexity of the composition.

Northern Aisle: The northern aisle features similar figurative mosaics,

including animals (real and mythical), human figures, and natural

motifs. These mosaics were added during the 6th-century remodeling and

are slightly more elaborate.

Iconography and Style: The mosaics

depict a wide range of subjects, including biblical scenes, early

Christian symbols, and personifications of the seasons, the ocean, the

earth, and wisdom. The vibrant colors and intricate designs reflect the

skill of the artisans and the church’s wealth. The style is comparable

to mosaics in Gaza and other Byzantine centers, situating Petra within a

broader artistic network.

Wall Mosaics: Fragments of wall mosaics

suggest that the church’s decoration extended beyond the floors, though

these are less well-preserved due to the fire and earthquakes.

The

mosaics are protected by the modern canopy and are a highlight for

visitors, offering a vivid glimpse into Byzantine artistry and theology.

Informational boards provide context, enhancing the visitor experience.

The Byzantine Church has yielded significant archaeological finds

that deepen our understanding of Petra’s Christian community and

Byzantine society:

Petra Papyri: In 1993, 152 carbonized papyrus

scrolls were discovered in a storage room, preserved by the fire that

destroyed the church. These 6th-century documents, written primarily in

Greek with Nabataean and Arabic terms, are the largest collection of

ancient written material found in Jordan. They include:

Property

contracts, tax records, out-of-court settlements, marriage agreements,

dowries, and inheritance documents.

A will dividing property

(including vineyards and slaves) among three brothers, likely part of

the family archive of Theodorus, an archdeacon of the church.

Records

spanning 528–582 CE, offering a snapshot of life in Petra during a

period of relative prosperity.

The papyri are still being deciphered

and are housed at the Jordan Museum in Amman, with publications (The

Petra Papyri, volumes I–V) detailing their contents.

Evidence of

Christian Life: The papyri and the church’s dedication to the Virgin

Mary confirm its role as a cathedral and the seat of the bishop. The

presence of Greek, Latin, and Nabataean names in the scrolls reflects

Petra’s multicultural population.

Construction and Destruction:

Excavations have revealed the church’s two-phase construction and its

destruction by fire and earthquakes. The carbonized scrolls and charred

remains of wooden elements (e.g., screens and furniture) provide clues

about the fire’s intensity.

Conservation Efforts: ACOR’s excavation

and restoration work, supported by USAID and the Jordanian Department of

Antiquities, has preserved the church and its mosaics. Ongoing

conservation ensures the site remains accessible to visitors.

The Byzantine Church is a key site for understanding the

Christianization of Petra and the broader Byzantine Middle East. Its

dedication to the Virgin Mary and its role as a cathedral highlight its

spiritual significance, making it a potential destination for Christian

pilgrims. The church’s mosaics and papyri reveal the wealth and cultural

sophistication of Petra’s Christian community, despite the city’s

declining economic status.

The church also reflects Petra’s

multicultural heritage, blending Nabataean, Roman, Hellenistic, and

Byzantine elements. This hybridism is evident in its architecture,

materials, and artistic styles, positioning Petra as a crossroads of

civilizations. The site’s location within the UNESCO World Heritage Site

of Petra enhances its global cultural value, attracting historians,

archaeologists, and tourists.

For visitors, the church offers a

serene and shaded retreat from Petra’s bustling main paths, with

panoramic views of the Colonnaded Street, Great Temple, and Royal Tombs.

Its spiritual ambiance, combined with its historical and artistic

richness, makes it a place for reflection and appreciation of Petra’s

layered history.

Location and Access: The church is located on a ridge overlooking

Petra’s city center, north of the Colonnaded Street and east of the

Temple of the Winged Lions. It is a 10-minute uphill walk from the

Colonnaded Street, accessible via the main trail through Petra’s

archaeological park. Visitors can reach Petra from Wadi Musa by car,

bus, or taxi, with parking available near the site entrance.

Visiting

Tips:

Visit early in the morning or late afternoon to avoid crowds

and heat. The canopy provides shade, but sturdy shoes, water, and sun

protection are essential due to uneven terrain and Petra’s desert

climate.

A local guide can provide deeper insights into the church’s

history and mosaics.

A small café near the church offers snacks, tea,

and restrooms.

Photography: The church’s mosaics and panoramic views

make it a popular spot for photography. The sheltered environment and

informational boards enhance the experience.

Guided Tours: Many tours

of Petra include the Byzantine Church alongside highlights like the

Treasury and Monastery. Multi-day tours from Amman, Eilat, or Tel Aviv

often cover the church as part of a broader Jordan itinerary.