Location: Tomar Map

Tel. 249 313 481

Open: June- Sep: 9am- 6:30pm daily

Oct- May: 9am- 5:30pm daily

Closed: 1 Jan, Easter, 1 May, 25 Dec

The Convent of Christ (12th – 18th century) is the name given to a

set of historic buildings located in the parish of São João

Baptista, city of Tomar, Portugal. The beginning of its construction

dates back to 1160 and is closely linked to the beginnings of the

Kingdom of Portugal and the role then played by the Templar Order,

where it had its Portuguese headquarters, having subsequently been

reconfigured and expanded by the heir to the Order of Christ.

Built over hundreds of years by some of the most important

medieval masters and architects working in Portugal (Diogo de

Arruda, João de Castilho and Diogo de Torralva, among many others),

this architectural complex includes diversified buildings, almost

all of remarkable importance. heritage, including the castle and the

Templar Charola, the 14th century cloisters, the Manueline church

and the Renaissance convent. Its present configuration reflects the

successive functions it was intended for and the architectural

typologies of the historical periods in which it was built. In it we

can find typically Romanesque, Gothic, Manueline, Renaissance,

Mannerist and so-called floor style elements.

"Art

compendium, and history compendium", many major figures in the

history of Portugal are closely linked to the Convent of Christ.

From the outset, the Templar master Gualdim Pais, the true founder

of the city of Tomar; Infante D. Henrique, responsible for an

important phase of conversion and expansion of the convent; D.

Manuel I, who ordered the construction of the 16th century church, a

true ex-libris of the Manueline style; D. João III, who implemented

a radical refoundation of the Order of Christ and the convent

itself, projecting his architectural preferences there; Philip II of

Spain, who extended the constructive program of the reign of D. João

III and held the courts there that recognized him as King of

Portugal.

The Convent of Christ stands out as one of the most

important monumental groups existing in Portuguese territory and is

classified as a National Monument (1910) and as a World Heritage

Site (1983).

Convento de Cristo is a denomination that generally

identifies an important architectural ensemble that includes the Templar

Castle of Tomar, the Templar Charola and adjacent Manueline church, the

Renaissance convent of the Order of Christ, the convent fence (or Mata

dos Sete Montes), the Ermida de Nossa Senhora da Conceição and the

conventual aqueduct (Aqueduto dos Pegões). Its construction began in the

twelfth century and lasted until the end of the seventeenth century,

involving a vast commitment of resources, material and human, over

successive generations. It is currently a cultural, tourist and even

devotional space.

12th-18th centuries

The castle was founded

by Gualdim Pais in the reign of D. Afonso Henriques (in 1160) and still

preserves memories of the time of these knight monks committed to the

reconquest; it comprised the walled village, the terreiro and the

military house located between the Mestre's house, the Alcáçova, and the

knights' oratory (the Rotunda or Charola). In 1357, forty-five years

after the extinction of the Templar Order, the castle became

definitively the seat of the Order of Christ, created in its place

during the reign of D. Dinis.

In 1420, Infante D. Henrique is

appointed governor and administrator of the Order of Christ and, from

then on, the exercise of governance of the Order will be handed over to

the royal family. The Order is reconfigured without detracting from its

original spirit of chivalry and crusade, but directing it towards a new

objective, that of maritime expansion, which the Order itself will

finance (it is with the Infante that the Knights become navigators and

that many sailors become knights of the Order of Christ). During his

regency, the branch of contemplative religious is introduced into the

Order, starting to coexist with that of the friars-knights; the castle's

military house is transformed into a convent, two cloisters are built

and the Alcáçova is adapted for the Infante's manor house.

Between 1495 and 1521 D. Manuel is King of Portugal, assuming the

position of governor and mayor of the Order, which in his reign will

have a deep involvement in the company of the Discoveries, holding an

immense power spread throughout the Portuguese empire. The convent will

be the scene of important expansion and improvement works, which are in

keeping with the spirit that presides over the reign of this monarch.

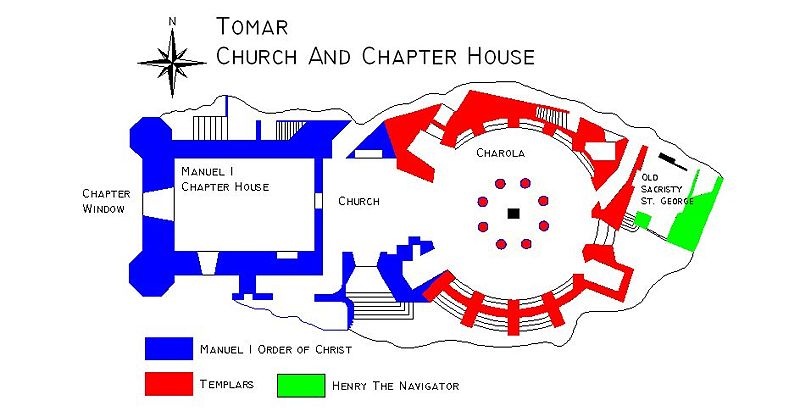

The Templar Rotunda is extended to the west, with the construction of an

imposing church/choir and sacristy outside the walls (begun by Diogo de

Arruda and completed by João de Castilho), where a renovating decorative

idiom (Manueline style) is put into practice that "celebrates the

Portuguese maritime discoveries, the mystique of the Order of Christ and

the Crown in a grandiose manifestation of power and faith".

Even

more than D. Manuel, D. João III will focus on Tomar many of his

initiatives, in line with the desire to turn that city into a kind of

«spiritual capital» of the kingdom, where he would like to be buried

(some historians admit having been this is the reason for the

construction of the small Church-Mausoleum of Nossa Senhora da

Conceição). From 1529 onwards, he ordered a profound reform of the Order

of Christ and the construction of a new convent space. The process is

led by Frei António de Lisboa, a noted humanist who implements a global

change in the institution, transforming the Order into a strict

cloistered order (inspired by the Rule of São Bento) and promoting the

construction of a large-scale convent. João de Castilho, the most

renowned architect/master builder of the time, would assume

responsibility for the work (c. 1532-1552), followed by Diogo de

Torralva (after 1554). The new buildings will appear to the west of the

castle and the Manueline Nave, according to a sober classicist style

that contrasts with the hyper-decorative character of the Manueline

style.

It is in the terreiro of the Convento de Cristo church

that the Courts of Tomar of 1581 take place, in which D. Filipe I

(Philip II of Spain) is acclaimed King of Portugal. Heir to the

Portuguese throne, Filipe I also becomes master of the Order of Christ.

The construction of the convent will continue during his rule and that

of his successors, with the completion of the Cloister of D. João III,

the construction of the Sacristia Nova and, to the south, the Aqueduct

(by Filipe Terzi). The northern flank also undergoes significant

changes, with the construction of the Portaria Nova and the Dormitório

Novo in the Cloister of the Hospedaria and, at the end of the 17th

century, the large Infirmary and the Botica nova, the last major works

carried out in the convent, at a later date. to the Restoration of

Independence.

19th-21st centuries

The 19th and 20th centuries

represent a troubled time of profound change for the Convent of Christ.

In 1811, French troops occupied the convent, leading to the destruction

of the remarkable choir stalls. In 1834, the extinction of the religious

orders suddenly put an end to monastic life in this male convent (by the

will of D. Maria II, the Order of Christ will nevertheless survive, in

the form of an Honorific Order; its Grand Master is, in present, the

President of the Portuguese Republic); An important part of its contents

is stolen, namely corner books on parchment with illuminations,

paintings and other artistic specimens. In the following year, many of

the convent's assets (such as the conventual enclosure, the enclosure of

the old town in the castle and the buildings on the south-west angle of

the convent), are sold at public auction to a private individual, the

future Count of Tomar, who transforms the west wing of the cloister of

Corvos in a 19th century mansion where he and his family will live for

several generations.

In 1845 D. Maria II, accompanied by D.

Fernando, settles in the convent; seven years later, D. Fernando ordered

the demolition of the upper floor of the Cloister of Santa Bárbara and

of the first and second floors of the south wing of the Cloister of the

Hospedaria to allow a better view of the facades of the 16th century

church, namely the Manueline window, to the west, which had been

obstructed by Renaissance buildings.

At the end of the 19th

century, several facilities were handed over to the military – such as

the old infirmaries, hospital, Sala dos Cavaleiros, Botica and cloister

da Micha – for occupation by the Regional Military Hospital; in 1917 the

entire complex, with the exception of the church, was taken over by the

Ministry of War. In 1939 the properties of the heirs of the Count of

Tomar were reacquired by the State. The disaffection of the spaces given

to the military sphere would take place later, in the last decades of

the 20th century, with the State taking full possession of the convent,

now with cultural and tourist functions, which remain.

Over the

years, there have been many actions to restore the Convent of Christ; to

them we owe the survival of the historical ensemble that we can admire

today. Among the most recent, the protracted restoration process of the

charola stands out (begun in the late 1980s and ended in 2013), which

revealed a long-hidden treasure: the trompe l'oeil paintings from the

Manueline period, " whose vision remarkably transforms the reading of

the charola's interior space".

Asset classification

Due to its

remarkable heritage value, the Convent of Christ is classified as a

National Monument (1910) and as a World Heritage Site (1983). UNESCO's

classification as a World Heritage Site was based on two criteria:

first, the Convent of Christ represents an exceptional artistic

achievement in terms of the primitive temple and sixteenth-century

buildings; on the other hand, it is associated with ideas and events of

universal significance, having been conceived at its origin as a

symbolic monument of the reconquest and becoming, in the Manueline

period, an inverse symbol, that of the opening of Portugal to external

civilizations.

The diverse set that makes up the Convent of Christ

was built between the 12th and 17th centuries, having undergone

successive adaptations that reflected the various types of use it

received and the stylistic characteristics of the architecture of the

different historical moments, sharing Romanesque, Gothic, Manueline,

Renaissance, Mannerist and so-called floor style.

In a very

simplified balance, of the initial buildings of the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries that have survived, the Castle and the Templar

Charola stand out (in Romanesque and Gothic styles); of the

interventions from the time of Infante D. Henrique in the 15th century,

the Gothic cloisters, to the northwest of Charola, and the ruins of Paço

do Infante should be noted; the initial 16th century intervention

(1510-1515) left us the Manueline church/choir, the wide enhancement of

the Charola's interior, the South Portal and an unfinished Chapter Room,

where the Manueline style predominates; the following works started c.

1532, corresponded to the construction of the vast convent in

Renaissance style (the Cloister of D. João III being Mannerist), which

externally involved the Manueline church and occupied an extensive area

to the west (including several cloisters, dormitories, refectory,

kitchen and other spaces intended for to monastic life); the last stages

of construction took place during the Philippine Dynasty and in the

period after the Restoration, corresponding to the construction, among

others, of the long block, in floor style, that delimits the convent

complex to the north/northeast (which housed the Portaria Nova or

Portaria Nova Filipina, the Infirmary and Botica) and the Aqueduct, to

the south.

Castle, Charola, Gothic Cloisters

The Castle of

Tomar consisted of a belt of walls and was divided into three spaces. In

the southern part was the village precinct (where the orange grove is

now located). On the highest part of the hill, to the north, the

military house of the Templars was established, flanked by the Master's

house (the Alcáçova; in ruins), with its keep and, to the west, the

knights' oratory (the Charola). . The vast courtyard of the castle, now

a landscaped space, separated these two enclosures.

The Charola

do Convento de Cristo was the private oratory (with probable burial

functions) of the Knights inside the fortress. Modeled on the

Paleo-Christian basilica of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, it is one

of the rare and emblematic rotunda temples in medieval Europe. According

to Paulo Pereira, its construction was carried out in two stages: the

initial one took place in the second half of the twelfth century (c.

1160-1190), in a time dominated by the Romanesque (it would be

interrupted due to serious skirmishes with the Almohads); the second,

the completion of the temple, about four decades later (c. 1230-1250),

already in the phase of full affirmation of the Gothic language in

Portugal. The result is a work that crosses elements of both styles

(Romanesque and Gothic). Charola's floor plan develops around a central,

octagonal space, which unfolds into sixteen faces on the outer wall of

the ambulatory. The interior of the central drum is covered by a dome

based on crossed ribs, of great verticality, and the ambulatory by a

barrel vault.

The building would undergo adaptations over time,

namely in terms of access, which was initially located to the east and

which, in the reign of D. Manuel I, would be carried out to the west,

through a triumphal arch (from João de Castilho) of communication with

the new Manueline church, in a formal and functional alteration that

transformed the Charola into the chancel of the new temple. The

liturgical valorization was then carried out through a comprehensive and

multifaceted intervention that included carving and parietal painting

programs and the integration of important pieces of sculpture and

painting, where names such as Jorge Afonso, Olivier de Gand, Fernão

Muñoz, Fernão by Anes, Gregório Lopes and Simão de Abreu (particularly

significant was the discovery of 16th century paintings of the

ambulatory vault, finally revealed in a recent restoration).

The

refurbishment and expansion of the monastery begun during the period of

the Infante's rule resulted, among other initiatives, in the

construction of two cloisters, in Gothic style, with a structure of

broken arcades on grouped columns. Adjacent to Charola, the Cloister of

the Cemetery is designed by Fernão Gonçalves and dates back to around

1420; the name is due to the fact that it was intended for the burial of

the friars and high dignitaries of the Order of Christ. The two-storey

Cloister of the Washes was originally the articulation between the

Cemetery Cloister and the Paço do Infante.

Stone game boards were

identified in the Lavagem Cloister and in the Corvos Cloister, which

were part of the daily lives of the clerics.

Manueline Church and South Portal

Between 1510 and

1513, the construction of the church took place, under the direction of

Diogo de Arruda. The new building was literally leaning against the

western face of the old Templar charola and took advantage of the uneven

terrain in that area to create a unified volume of great grandeur (the

exterior impact would, however, be seriously affected by the later

construction of the adjacent Renaissance cloisters), and creating,

inside, the overlapping spaces of the sacristy and the upper choir

(where a remarkable choir by Olivier de Gand was installed, which would

not survive the heritage devastation that occurred during the French

Invasions). The whole, in particular the western façade, presents a

profusion of decoration endowed with a deep mythographic symbolism that

crosses the Christological and Marian symbols with those of royal

heraldry. The famous window on the western façade in particular,

conceived as an «inflamed poem of stone», is inscribed in a vast

vestment (girded with buttresses and animated with sculptures of the

four «kings in arms» of the kingdom), revealing the ornamental program

of terrestrial flora and fauna and echoes of the Discoveries adventure,

emblematic of the Manueline style.

The work would be completed in

1515, in a second contract in which the new manager, João de Castilho,

was in charge of dealing with several issues that had remained

unresolved in the previous contract, including the construction of the

vault of the new Manueline church/choir, the connection between it and

the charola and the creation of a new and monumental gateway to the

temple. The ribbed vault, with a single flight, that covers the church,

gives unity to the space and enhances the interior lighting, coming from

four windows (two to the south and two to the north) and a circular

oculus on the west facade. The vault is divided into three panels,

supported by eight corbels with plant and figurative decoration. Between

the church/choir and the charola was opened a wide broken arch that

ensures an effective integration between the two spaces. Finally, a

portal-retable was built to access the temple where João de Castilho

tested a modular system that he would use again in the south portal of

the Jerónimos Monastery.

The south portal of Tomar takes

advantage of the thickness of the church's wall to create an

architectural canopy that tops and protects the sculptural ensemble, in

which several symbolic figures of prophets, mitred clerics, Doctors of

the Church were integrated, in which, in the center, the image of the

Virgin Queen of Heaven, with the surmounting cross of Christ. From a

stylistic point of view, there is a fusion between Manueline and Gothic

influenced by the decorative lexicon of the Renaissance, through a type

of ornamentation that was very widespread in Spain, the Plateresque. In

the 1515 undertaking, the construction of the Chapter Room was also

started, which would remain unfinished.

renaissance cloisters

The overall layout of João de Castilho's Renaissance renovation and

expansion followed a rational (and functional) concept. Two long

corridors in a cross articulate four main cloisters, which together

delimit an enormous quadrilateral; they are the Cloister Grande (or of

D. João III), the Cloister of the Hospedaria, the Cloister of Corvos and

the Cloister of Micha. A fifth cloister, of more modest dimensions, was

placed against the western facade of the Manueline church, seriously

affecting its visibility. From a functional point of view, this cloister

– Cloister of Santa Bárbara –, came to occupy a key place, in the

transition between the old and the new buildings. It would have been the

first to be built (c. 1531-1532) and its stylistic characteristics

immediately reveal a radical break with the hyper-decorative density of

Manueline and the option for a new classicist idiom. The first floor of

this cloister was demolished in the mid-19th century in order to restore

visibility to the façade of the Manueline church, in particular the

famous Manueline window. Finally, note the small Cloister of Necessárias

(a protruding block on the west façade of the convent complex), intended

exclusively for sanitation.

The Cloister of the Hospedaria was

intended to welcome visitors to the convent and therefore has a noble

appearance. It preserves features identical to what must have been the

initial Castilian Grand Cloister, allowing us to imagine in general

terms what this lost construction would have been. Buttresses of

quadrangular section, along the entire height of the cloister, give

rhythm to its elevations. Covered by rib vaults, the galleries on the

ground floor are made up of four sections, with a double round arch

supported on columns with ample capitals; the first floor is covered by

wooden beams with caissons, being formed by an architrave based, in the

center, on an Ionic column; the west side of the cloister has an

additional floor, solved in the same way as the first floor. The formal

balance of this cloister was seriously disturbed by the subsequent

demolition, to the south, of the gallery on the first floor (for reasons

identical to those that dictated the amputation of the Santa Bárbara

Cloister), and by the construction, to the north, of the inelegant body

of the so-called Portaria Nova , which distorts the balance of this

facade. The Cloisters of Corvos and Micha are organized in a basically

similar way to the Hospedaria, although they have a smaller scale and a

simpler level of finishing, since they are different functional areas,

intended for the novitiate and assistance.

Cloister of D. João

III

The original Cloister Grande – or Cloister of D. João III – was

almost entirely dismantled after João de Castilho's death, for reasons

that remain to be fully clarified. It was replaced by the remarkable

Mannerist version by Diogo de Torralva, considered a masterpiece of this

architect and of European Mannerism. The construction works would be

extended by Francisco Lopes after Torralva's death (in 1566), with the

final finishes (by Filipe Terzi) and the central fountain (by Pedro

Fernandes de Torres) carried out already in the time of Philippine

domination. A top piece in 16th century European architecture, this

cloister reflects the early assimilation of the most erudite Mannerist

values.

The Cloister of D. João III de Torralva reveals an

absolute mastery of classical language, influenced by Books III and IV

by Sebastiano Serlio and, probably, by inspiring works such as Villa

Imperial de Pésaro (c. 1530), adapting them to the program from Tomar.

The work interprets the same classic syntagm, but now informed by the

experience of the High Renaissance. Monumentality and scale play a

decisive role here through the careful proportion of the spans and

supporting elements. "The result is a body of galleries of a diaphanous

transparency", of a soft luminosity, reverberated by the soft stone of

warm color; "The values of light and shadow are accentuated by the

play of chromaticism of the surfaces, which mostly use yellow limestone,

in contrast to the black marble of the recessed planes".

Dorms

and Cruise, Refectory, Novitiate

The long corridors on the upper

floor of the bedrooms are covered by extensive barrel vaults with

typical classicist oak coffered ceilings; at the place where they cross

they form the Cruzeiro itself, an interesting architectural piece

designed by Castilho with the assistance of Pedro Algorreta which has a

chapel adjacent to the image of the Seated Christ or Senhor da Cana

Verde, 1654 (terracotta sculpture by Inácia da Encarnação) . Decorated

in relief (garlands, putti…) and covered by a lantern with a dome in a

«clergyman's cap», the cross punctuates the intersection of corridors

and alters the clean and uncluttered architecture of the set. The

refectory room is covered by a barrel vault, based on a continuous

cornice and with caissons delimited by ribs in stone, of quadrangular

section and classical configuration. Two pulpits, located opposite each

other on the longer walls, display symbolic Renaissance motifs.

On the first floor of the west façade of the Micha cloister, the three

novitiate rooms stand out. Each of them seeks in some way to emulate

Vitruvius' hypostyle room; the first two (for the novices' dormitory)

have an arched space, covered in wood, supported by four central columns

with Ionic capitals; in the third, square one – the Chapel of the

Novitiate or Dos Reis Magos –, "the architect [João de Castilho] built

one of the Portuguese Renaissance masterpieces." The roof of this room,

which completes the floor, is formed by the intersection of two wooden

barrel vaults (with coffered ceilings), supported by architraves resting

on Corinthian columns with composite capitals, the four central ones

being perfectly highlighted and the remaining twelve adjacent to each

other to the boundary walls.

Aqueduct, New Gate and Monastic Infirmary

Built in

the era of Filipe II of Spain, the Pegões Aqueduct was designed by

Filipe Terzi. This is a large-scale hydraulic engineering work of

approximately 6 kilometers in length, with a total of 180 arches for the

overhead passages of the pipeline. The stretch over the Pegões valley

stands out, consisting of 58 round arches, in the deepest part of the

valley they are based on 16 broken arches, in turn built on imposing

masonry massifs. The aqueduct ends with a row of large arches attached

to the south façade of the convent.

On the opposite side, to the

north of the convent complex, is the "long and monotonous" body of the

so-called Portaria Nova. Built in the 17th century, in the ground style,

"without any stylistic imitations", it integrates the Infirmaries and

the Apothecary. With an entrance to the north, Portaria Nova includes a

staircase in 3 flights, with ashlars of blue and white patterned tiles,

being preceded by a small vestibule (in the open), ending in the Sala

dos Reis, a quadrangular space with tiles identical to the of the

staircase and painted wood paneled ceiling. The New Sacristy, in a

mannerist style, was also built during the Philippine Dynasty.

Chapel of Our Lady of Conception

Located close to the Convent of

Christ, the Chapel of Nossa Senhora da Conceição was (according to the

proposal of the historian Rafael Moreira) conceived as a

mausoleum-church for D. João III and his relatives (this testamentary

wish of the king would not, in the however fulfilled by his successors).

With a quadrangular outline, this small chapel was one of the last works

by João de Castilho; its interior configuration is identical to that of

the Novitiate Chapel, although in this case entirely in stone. It would

be completed by Diogo de Torralva (whose stylistic mark is particularly

noticeable abroad) after Castilho's death.

"The beautiful

exterior is far surpassed by the interior", not very spacious, where a

reflection of the first Italian renaissance hovers; this one has three

naves covered by barrel vaults over exquisite Corinthian columns, the

transept being identically covered by a barrel vault.[30] "The chapel

can be rightly considered one of the jewels of the European Renaissance.

Its intriguing perfection, especially in the interior, [de Castilho] of

a unique harmony in Portuguese and Peninsular architecture, makes it a

true example of Renaissance language in architecture. "