Location:

Map

Open: May-

Oct

Nearest town:

Werfen- 3 miles (5 km)

Transport:

Car or train from Salzburg to Werfen than

a bus to the car cable

Official

site

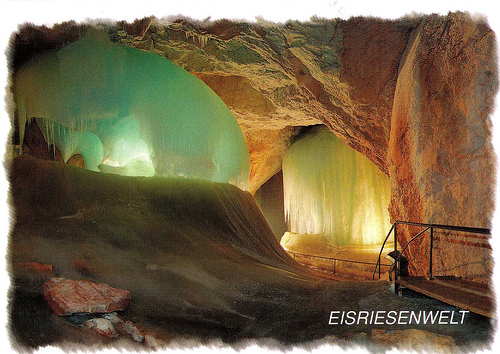

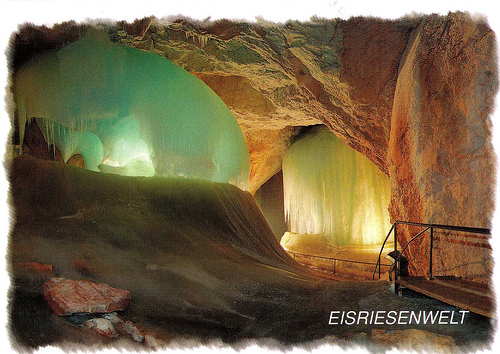

Eisriesenwelt, which translates from German as "World of the Ice Giants," is the largest accessible ice cave in the world. This natural wonder is a labyrinthine system of limestone and ice formations, renowned for its breathtaking frozen landscapes that evoke a mythical, otherworldly realm. Located in Werfen, Austria, approximately 40 km south of Salzburg, the cave is embedded within the Hochkogel mountain in the Tennengebirge section of the Alps, at an elevation of about 1,656 meters (47°30′11″N 13°11′25″E). It attracts around 200,000 visitors annually, offering a glimpse into a frozen subterranean environment that remains below freezing year-round, even in summer. The cave's name draws inspiration from Norse mythology, particularly the Edda saga, reflecting the gigantic ice structures that dominate its interior. Locally, it was once feared as a "gateway to Hell" due to the howling winds and icy mists emanating from its entrance, a belief that deterred exploration for centuries.

The formation of Eisriesenwelt dates back approximately 100 million

years to the late Tertiary period, when tectonic shifts during

mountain-building processes (Alpine orogeny) created initial crevices

and fissures in the limestone rock of the Tennengebirge karst plateau.

Over millennia, chemical dissolution by rainwater and mechanical erosion

by the Salzach River widened these fissures into expansive cavities and

passageways. The cave system continued to evolve during the

Pleistocene's Würm glaciation, shaping the broader mountain range.

Unlike static caves, Eisriesenwelt is classified as a dynamic ice cave,

featuring vertical chasms and corridors that connect lower entrances to

higher openings, functioning like a natural chimney for airflow.

The

ice formations result from a seasonal cycle: In winter, warmer air

inside the cave rises, drawing in cold external air that cools the lower

sections below 0°C (32°F). In spring, meltwater from thawing snow seeps

through rock fissures into this supercooled environment and freezes,

building up layers of ice. During summer, cold air from deeper within

the cave blows outward, preventing melting and preserving the ice. This

process creates stalactites, stalagmites, frozen waterfalls, columns,

and expansive ice embankments. The oldest ice layers are estimated to be

around 1,000 years old, and the cave is still actively growing as new

water carves additional passageways. Scientific research, including ice

core studies, has revealed low ion content in the ice and distinct

cryocalcite layers, providing insights into past climates. While much of

the cave system has stabilized due to reduced water flow in some areas,

the Alpine location ensures ongoing development in others.

Eisriesenwelt spans a total length of over 42 kilometers (about 26

miles), making it the world's largest ice cave system. However, only the

first kilometer (0.6 miles) is perpetually covered in ice and open to

the public via guided tours; the remaining 41 kilometers consist of bare

limestone and are reserved for scientific exploration. The cave descends

about 400 meters underground at its tourist endpoint.

Notable

features include:

Posselt Hall: A large chamber with the central

Posselt Tower, a prominent ice stalagmite marking the extent of the

initial 1879 exploration.

Great Ice Embankment: A massive

25-meter-high (82-foot) ice wall, representing the area of maximum ice

accumulation, which visitors must ascend via steps.

Hymir's Castle:

Named after a Norse giant, this section features intricate stalactites

forming "Frigga's Veil" (resembling a curtain) and the "Ice Organ"

(pipe-like formations).

Alexander von Mörk Cathedral: A vast dome

honoring the early explorer, with dramatic ice sculptures.

Ice

Palace: The tour's climax, located 1 km in and 400 meters underground,

showcasing frozen waterfalls and ethereal ice designs.

Other

elements include the Sturmsee (a frozen lake) and various side branches

like the dry Wimur passage. The cave's interior is illuminated solely by

carbide lamps during tours, enhancing the shadowy, mystical ambiance

without electricity.

For centuries, locals in Werfen knew of the cave's entrance but

avoided it, convinced it was an entrance to the underworld due to the

cold winds and fog billowing out. The official discovery occurred in

1879 when Anton von Posselt, a Salzburg naturalist, ventured 200 meters

inside, marking his turnaround point with the "Posselt-Kreuz" (Posselt

Cross) due to steep ice and limited equipment. He published his findings

in a mountaineering journal in 1880, but the cave was largely forgotten.

Rediscovery came in 1912, led by Alexander von Mörk, a speleologist and

founder of the Salzburg Section of the Association for Speleology. With

companions like Benno Pehany, Erwin Angermayer, and Herrmann Rihl, they

overcame the Great Ice Wall using carved steps and better gear,

exploring horizontal sections including the Sturmsee and naming the cave

Eisriesenwelt. Expeditions paused during World War I, where Mörk died in

1914; his ashes are interred in a niche in the cave's cathedral.

Post-war exploration resumed in 1919 with figures like Walter von

Czoernig-Czetwertynski and the Oedl brothers, who mapped 18 kilometers

by 1920, including domes like the "Dom des Grauens" (Dome of Horror).

Connections to nearby caves like Sulzenofen were investigated.

By 1920, the Forscherhütte (Explorer's Hut) was built, establishing mountain routes and attracting the first tourists, turning the cave into a "world sensation." In 1924, wooden walkways were added for safety. The Dr. Oedl House followed, along with paths from Werfen and Tenneck. A major advancement came in 1955 with the construction of a cable car (Austria's steepest gondola), reducing the ascent time from 90 minutes to just 3 minutes. Today, the cave is owned by the National Austrian Forest Commission and leased to the Salzburg Association of Cave Exploration since 1928, which manages operations and shares revenue. Exploration beyond the tourist zone continues for scientific purposes.

Eisriesenwelt is open seasonally from May 1 to October 31 (as of

2025), daily from 8:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m., with visitors advised to

allocate about 3 hours for the full experience. All visits are via

guided tours lasting approximately 75 minutes, conducted in groups with

multilingual guides covering geology, ecology, glaciology, and history.

Tours start at the entrance, proceed through key features, and loop back

out, involving about 1,400 steps (700 up and 700 down) over 1.5 km.

Photography is prohibited inside to preserve the experience.

Accessibility requires physical fitness due to the terrain: From the

parking lot, it's a 20-minute walk to the cable car, a 3-minute ride up,

and another 20-minute hike to the entrance (over 400 feet elevation

gain). The entrance is 124 meters above ground level. For those

preferring a challenge, a footpath over alpine terrain bypasses the

cable car. The cave is kid-friendly but demanding due to slippery ice;

it's also dog-friendly, though suitability varies. Warm clothing, sturdy

shoes, hats, and gloves are essential, as temperatures hover around 0°C

(32°F). Online tickets offer discounts and timed slots (30-minute

windows), with group rates for 20+ people and school trips requiring

reservations. For current pricing, visitors should check the official

website, as rates may vary.

Tips for visitors include arriving early

to avoid crowds, preparing for the physical demands, and considering the

cave's closure from November to April due to weather. Wildlife is

minimal in the icy tourist areas but may exist deeper in the limestone

sections.

What sets Eisriesenwelt apart is its blend of natural artistry and human history: the interplay of light from handheld lanterns on ice sculptures creates a haunting, underworld vibe, true to its "gateway to Hell" moniker. As a living geological site, it offers insights into climate history through its ice layers and continues to inspire awe as a testament to nature's sculptural power. Its status as a protected site underscores its ecological value, with no flora or fauna in the frozen zones but potential biodiversity in deeper, warmer areas. For adventurers, it represents a rare opportunity to step into a frozen time capsule in the heart of the Alps.