Address: Regio VII, Insula 4

Area: 870 square meters

Rooms:

17

The House of the Figured Capitals, also known as Casa dei

Capitelli Figurati or the House of the Coloured Capitals, is a large

ancient Roman domus (townhouse) in Pompeii, Italy, located at

VII.4.57 on the south side of Via della Fortuna (Strada della

Fortuna 6) in Insula 4. Covering approximately 870 square meters

with 17 rooms, it exemplifies the spacious and luxurious residences

of Pompeii's elite during the first century CE. The house derives

its name from the distinctive carved capitals atop the entrance

pilasters, featuring mythological figures such as satyrs, maenads,

and human couples, which served both decorative and possibly

symbolic purposes. Severely damaged by the 79 CE eruption of Mount

Vesuvius, much of the structure collapsed, leaving it in ruins with

limited surviving decorations, though remnants suggest it belonged

to a wealthy citizen with refined tastes. At the time of the

disaster, parts of the house had been repurposed as a weaver's

workshop, indicating shifts in usage amid Pompeii's evolving urban

economy.

Excavated primarily in the early 19th century, the House of the Figured Capitals was partially uncovered in 1831, with major work occurring from June 1832 through 1833, and additional explorations in 1836. The site was documented by archaeologist F.M. Avellino in his 1837 publication, providing early descriptions of its features. Graffiti on the exterior walls, discovered as early as March 1831 and September 1829, includes election slogans supporting local candidates like Marcus Cerrinius Vatia for aedile (CIL IV 277), Fuscus for aedile (CIL IV 278), and Quintus Postumius for quinquennial magistrate (CIL IV 279), offering insights into Pompeii's political life and suggesting the owner's involvement in civic affairs. The house's conversion into an officina textrinum (weaver's workshop) by 79 CE, evidenced by loom placements and worker names in graffiti, reflects economic adaptations in the city, possibly due to post-earthquake recovery efforts after the 62 CE tremor. Historical records, including 19th-century drawings and photographs, capture the site's post-excavation state, with artifacts like the entrance capitals later displayed in Pompeii's Antiquarium and Forum Granary.

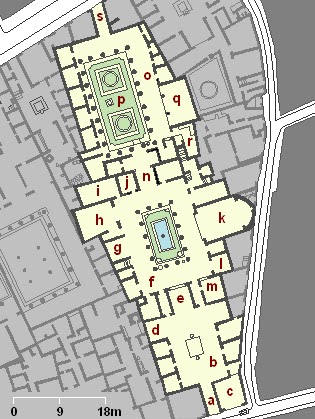

The House of the Figured Capitals follows a

traditional Roman domus plan, adapted to Pompeii's urban density, with a

focus on inward-facing spaces for privacy and light. Entry is through a

vestibule flanked by the iconic figured capitals on pilasters. This

leads to a rectangular atrium, the central hub, featuring an impluvium

(rainwater basin) with a fluted edge on its south side for aesthetic and

functional water collection. Surrounding the atrium are various rooms:

In the northeast corner, a medium-sized room illuminated by a narrow

north-facing window.

Southeast: A service room with remnants of a

staircase to an upper floor, likely for additional living or storage

space.

South of the service room: Two small cubicula (bedrooms), one

connected via a narrow doorway to an ala (wing or alcove).

Western

side: Another cubiculum linked to an ala, and a central room with

brick-lined northern and southern walls.

A doorway in the central

room's northeast corner accesses the triclinium (dining room),

emphasizing social entertaining.

Beyond the atrium, a peristyle

(colonnaded courtyard) serves as a secondary open space, surrounded by

porticoes on the north, east, and west sides, with the west portico

incorporating columns built into the wall for structural support. Room

16, adjacent to the peristyle, housed a kitchen, latrine, and

upper-floor stairs, connected by a corridor to the east portico. Room 17

is a small remnant space, while Room 18 relates to the peristyle area.

The layout reflects efficiency, blending public reception areas with

private quarters, though much was ruined by the eruption.

Despite extensive damage, the house's decorations highlight Pompeian

artistry, though many are lost or faded. The entrance capitals are

the standout feature: The right (west) pillar shows a man and woman

facing inward and a drunken satyr with a maenad facing the street;

the left (east) depicts a satyr chasing a maenad outward and another

couple inward. These carvings, portraying naked torsos and robed

figures in romantic or mythological poses, likely symbolized

protection or prosperity. Atrium and hallway walls retain damaged

plaster, obscuring original frescoes, but suggest costly designs. In

the peristyle, wall paintings on the north portico's west wall are

documented in 1849 drawings by Laurits Albert Winstrup and Fredrik

Wilhelm Scholander, with surviving fragments confirming their

accuracy. No specific mosaics are detailed, but the overall opulence

implies intricate flooring.

The peristyle garden, visible from

multiple vantage points, provided a serene outdoor space, though

altered by its workshop conversion. A key religious element is the

aedicula lararium (household shrine) against the peristyle's west

wall, built on a masonry podium with a rectangular niche for deities

or ancestors. Graffiti in the peristyle names weavers (Texe(ntis)

Erati, Tiburtinus, Crescentis) and loom locations, underscoring its

industrial repurposing. In the northeast peristyle corner, a marble

column bears a carved sundial—an oblique circular cone with 11 hour

lines, though flawed in design by terminating short of the summer

solstice extension.

Excavations yielded few portable artifacts due to the site's devastation, but notable finds include the sundial, discovered on July 14, 1837, and now housed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. The figured capitals themselves, removed for preservation, are displayed in Pompeii's on-site museums, with photographs from 1956 onward documenting their condition. Election graffiti on the facade provides epigraphic evidence of political engagement. No major hoards or personal items are recorded, likely due to evacuation or looting post-eruption.

The House of the Figured Capitals illustrates the social and economic dynamics of late Pompeii, from elite luxury to adaptive reuse as a workshop, highlighting resilience after the 62 CE earthquake. Its mythological decorations reflect Roman fascination with Greek-inspired themes, blending art with daily life. As part of Pompeii's UNESCO World Heritage site, it contributes to understanding domestic architecture, urban evolution, and the abrupt halt of a thriving society, with features like the sundial offering rare glimpses into ancient timekeeping technology.