Mamayev Kurgan, often referred to as Mamayev Hill or Height 102.0 on military maps, is a commanding elevation rising approximately 102 meters above the Volga River in Volgograd, Russia (formerly known as Stalingrad). This site is etched into history as a central battleground during the Battle of Stalingrad, one of the bloodiest and most decisive confrontations of World War II, spanning from July 23, 1942, to February 2, 1943. The hill's name originates from the Tatar word "kurgan," meaning tumulus or mound, and is linked to the 14th-century Golden Horde commander Mamai, though archaeological evidence suggests prehistoric burial mounds in the area. Its modern prominence stems from the ferocious fighting that took place there, where control shifted hands up to 15 times, resulting in staggering losses—estimates indicate that the soil still holds 500 to 1,250 fragments of metal and bone per square meter, a grim testament to the intensity of the combat. Today, it hosts an expansive memorial complex spanning about 26 hectares, dedicated to the heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad, embodying themes of Soviet resilience, maternal sacrifice, and the triumph over fascism. Recognized for its cultural and historical value, it has been on UNESCO's tentative list for World Heritage status since 2014, symbolizing global acknowledgment of its role in commemorating one of history's greatest battles.

The Battle of Stalingrad was a pivotal turning point on the Eastern

Front, where the Soviet Union halted the Nazi advance into the USSR.

Mamayev Kurgan was strategically crucial due to its elevated position,

offering panoramic views over the city, the Volga River crossings, and

key industrial districts, allowing for effective artillery observation

and fire control. On September 13, 1942, the German Sixth Army launched

a massive assault, capturing the hill after brutal close-quarters

combat, only for the Soviets to counterattack. The freshly arrived 13th

Guards Rifle Division, commanded by General Alexander Rodimtsev, crossed

the Volga under heavy fire and recaptured the summit on September 16,

but at a horrific cost—nearly all 10,000 men were killed or wounded

within days. The hill saw repeated assaults; by late September, Germans

held the northern slopes while Soviets clung to the southern ones. Key

units like the 284th Rifle Division, including legendary sniper Vasily

Zaytsev (famous for his duels with German marksmen), defended positions

until relieved in January 1943 during Operation Uranus, the Soviet

encirclement that trapped and defeated the German forces. The fighting

was so intense that the landscape was obliterated—trenches filled with

bodies, craters from incessant shelling, and the earth turned black from

fires and explosions, preventing grass growth for years postwar. Total

Soviet casualties in the battle exceeded 1.1 million, with over 34,500

soldiers buried in mass graves on the hill alone, including notable

figures like Marshal Vasily Chuikov (commander of the 62nd Army, the

only Marshal buried outside Moscow) and Zaytsev (reburied here in 2006).

The German surrender on February 2, 1943, marked the end, but the hill's

scars remain, with unexploded ordnance and human remains occasionally

unearthed even today.

Postwar, the site was designated for

memorialization to honor the "Great Patriotic War." Construction began

in May 1959 under sculptor Yevgeny Vuchetich and engineer Nikolai

Nikitin (known for the Ostankino Tower), facing engineering challenges

like unstable soil from wartime damage and groundwater erosion. The

complex was completed and unveiled on October 15, 1967, during the

Soviet era's emphasis on war heroism, costing millions of rubles and

involving innovative prestressed concrete techniques to stabilize

structures on the shifting terrain.

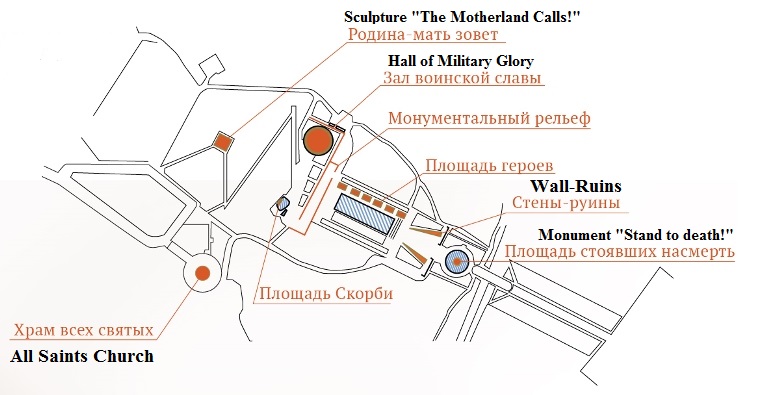

Designed as a symbolic pilgrimage, the complex guides visitors on an

ascending path from the base to the summit, representing the progression

from despair and battle to victory and eternal remembrance. The layout

integrates architecture, sculpture, and landscape in a socialist realist

style, with granite pathways, reflective pools, and inscriptions drawn

from real soldiers' letters and oaths. Entry begins at the southern foot

via the Avenue of Poplars, lined with trees symbolizing renewal.

The

introductory "Memory of Generations" is a 17-meter bas-relief showing a

diverse procession—soldiers, civilians, and children—carrying wreaths

and banners, evoking communal mourning and tribute across eras.

Ascending, visitors reach the "Stand to the Death!" sculpture: a

colossal, muscular soldier bursting from rocky ruins, armed with a

submachine gun and grenade, inscribed with "...And not a step back!"—a

reference to Stalin's Order No. 227, emphasizing unbreakable Soviet

resolve amid encirclement.

Next is the Square of Those Who Fought to

the Death, flanked by "Ruined Walls" etched with battle scenes,

closed-eyed soldier faces (symbolizing the fallen), and authentic

wartime graffiti like pleas for vengeance. Audio elements recreate

gunfire and shouts, immersing visitors in the chaos.

The Square of

Heroes features a large reflective pool and six heroic sculptures:

depictions of unyielding defenders, nurses aiding the wounded, sailors

in combat, officers rallying troops, a banner-bearer saving the flag,

and victors over defeated enemies, all underscoring collective heroism.

Inscriptions here, such as "With an iron wind blowing straight into

their faces, they were still marching forward," highlight superhuman

endurance.

At the core lies the Hall of Military Glory, a circular

pantheon opened in 1963 for the battle's 20th anniversary. Its exterior

boasts reliefs of celebrating soldiers; inside, an Eternal Flame burns

in a massive hand-shaped torch, encircled by walls listing 7,200 names

of the fallen in golden mosaic. A perpetual honor guard changes hourly,

and solemn music (like Shostakovich's works) plays softly; visitors

maintain silence as a mark of respect. The ceiling bears: "Yes, we were

mere mortals, and few of us survived, but we all fulfilled our patriotic

duty to our sacred Motherland!"

Higher up, the Square of Sorrow

presents a heart-wrenching sculpture of a mother cradling her dying son

in a pool of "tears," capturing personal grief amid national tragedy.

The pinnacle is "The Motherland Calls!"—an 85-meter-tall (including

the 27-meter sword) concrete colossus weighing 8,000 tons, depicting a

woman summoning her people to defend the homeland. Inspired by the

Winged Victory of Samothrace, its dynamic pose and billowing robes

convey urgency; the sword, originally titanium but replaced with

stainless steel in 1972 to reduce wind noise, points defiantly.

Engineering feats include a thin shell (18-32 cm thick) reinforced by

steel cables, though tilting issues (up to 20 cm by 2003) prompted

restorations in the 2010s, including foundation reinforcements and LED

lighting. At its base lie mass graves and a church added in 2005,

blending secular and spiritual remembrance.

Mamayev Kurgan transcends a mere monument; it's a sacred site in Russian culture, attracting over 2 million visitors annually for reflection, education, and ceremonies like Victory Day on May 9. It influences art, literature, and film—featured in works like Enemy at the Gates (depicting Zaytsev) and Soviet propaganda—and stands as a "dark tourism" destination, highlighting war's horrors. Symbolically, it represents motherhood calling for sacrifice, immortalizing the Soviet spirit against invasion. Recent efforts include pushes for UNESCO inscription, with discussions in 2025 emphasizing its two original peaks (one now under the Church of All Saints). Open 24/7 and free, it's best visited at dawn or dusk for atmospheric views, though visitors must respect rules like staying off the grass and maintaining silence in sacred areas. As a beacon of memory, it ensures the lessons of Stalingrad endure, warning against the costs of conflict while celebrating human fortitude.