Location: 40 km (25 mi) West of Valladolid, Yucatan

Best time to visit: October- March

Open: 8am- 5pm daily

Chichén-Itzá is probably the best-preserved ruins

of the Maya culture on the Yucatán, and it is certainly the most

visited. When a Crusader ship docks in Cancún, a good dozen buses

are already waiting to take the passengers to the temple complex.

With over 8,000 visitors daily, this attraction is now the second

most visited archaeological site in Mexico after Teotihuacán.

According to legend, the king of Tula, Ce Acatl Topiltzin

Quetzalcoatl, migrated from central Mexico to the far-off Yucatán to

become a star himself while his entourage tended to Chichén Itzá.

This cannot be proven, but there are surprisingly many similarities

with Tula, so that today Tula is often referred to as the prototype

of Chichén Itzá.

Archaeologically, settlements could be

proven up to the pre-classic period, without the settlement being

able to gain great importance. In the classical period, however, it

became a city with its own royal seat. At first she was still in the

shadow of Ek Balam. According to the inscriptions, the change took

place around 900 AD, which is also architecturally recognizable.

Buildings from this period increasingly contain Toltec style

elements, which are often associated with the legend of Tula.

However, the king of Tula is only said to have lived in the 11th

century. AD left their original homeland, which raises some

questions. In any case, Chichén Itzá increasingly developed into a

cultural and religious center, even if the latest findings show that

Chichén Itzá's direct dominion only extended over part of the

Yucatán Peninsula. Good relations with some ports and the resulting

direct access to the most important trade routes strengthened the

city's position. In the south, spheres of influence of the Mayan

metropolis of Cobá could be removed. A military victory over the

city of Yaxuná, which was allied with Cobá, in 950 AD could be

proven. At the beginning of the 13th century there were armed

conflicts, including with the metropolis of Mayapán. Another legend

here describes the three allied cities Chichén Itzá, Mayapán and

Izamal. According to the story, the then king of Mayapán Hunac Ceel

gave the ruler of Chichén Itzá Chac Xib Chac a love potion, so that

he fell madly in love with the bride of the king of Izamal and

kidnapped her. So it was easy for Mayapán to find enough allies to

attack Chichén Itzá. They finally defeated Chichén Itzá and

devastated the city. In the following years the regional influence

of Chichén Itzá decreased and the Itzá moved from here to Lake Petén

Itzá in Guatemala to found their new capital Tayasal. Chichén Itzá

was eventually abandoned.

The Spaniards only found abandoned

temples here. The city was rediscovered archaeologically in 1840.

But it wasn't until a year later that the city really took center

stage with the visit of John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick

Catherwood. Stephens' stories, and especially Catherwood's drawings,

enthralled the world.

Today, Chichén Itzá is a UNESCO World

Heritage Site and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. Since

access to all buildings is currently blocked, one or the other view

escapes, but the complex remains impressive. And if you enter the

facility early in the morning, you will often find the facility

beautifully shrouded in wafts of fog and deserted.

Pictures don’t give enough credit to the magnitude and size of

the city. Without a doubt Chichen Itza is one of the most impressive

construction complexes of the pre- Columbian Era. Climbing and

exploring the city might easily take the whole day. The best time to

get there is early in the morning when the jungle is full of birds

and animals. Although the site opens at 8 am you can ask for an

yearly admission. Prepare to whine, cry and beg if you really want

it. If you will be good enough security might let you in. Empty

massive structures of Chichen Itza along with sounds and presence of

the wildlife makes this archaeological site an unforgettable

experience. Around noon tourists form a huge line at the entrance

and scare all the wildlife.

Little is known about origins of

history of Chichen Itza. Its role as major regional centre is

approximately dated from the Late Classic to Early Post-classic

period. Unlike many other Mayan cities, Chichen Itza was not

governed by a single ruler. Instead all decisions were made by a

counsel of elders.

Most of buildings in the southern part of

the city were build by Maya between 700AD and 900 AD. Temple of

Kukulkan, Temple of Warriors and Ball Court were build later and

show Toltec influence. Cultural diffusion brought new styles to

Chichen Itza, new deities and of course human sacrifices on an

unprecedented scale. Artefacts found on the size indicate that

Chichen Itza was centre of wide trade web from North Mexico to

Panama. Historians are uncertain reasons and time of the decline of

this metropolis. Some evidences indicate that overpopulation and

subsequent starvation caused the city to decline by 1000 AD. Other

sources blame the downfall to rebellion and civil war that broke out

in 1221. Burned ceiling over Temple of the Warriors and Great Market

certainly suggest this course of violent actions. Regardless that

was the core reason for such decline or combination of such Chichen

Itza never recovered. Although it was not fully abandoned and temple

were used for worship of old Gods until arrival of the Spaniards, no

new monuments were build. In 1531 conquistador Francisco de Montejo

tried to turn Chichen Itza into a new capitol of the Spanish

province. Maya rebellion cancelled these plans and drove him out of

Yucatan peninsula.

The city is in very good condition and literally overflows with

well-restored buildings and beautifully preserved reliefs. If you add

the buildings in the area, it is not possible to see them all in one

day. Even on the hotel grounds, partially restored structures can still

be found. But from the wealth of buildings, some stand out and make for

a breathtaking day trip across the site. Overall, the complex is divided

into a southern and a northern part. The southern part is mainly in the

Puuc style and offers most of the characters with dates. The northern

part lies on an artificial platform and can show many Toltec stylistic

elements.

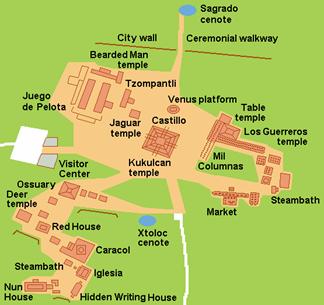

No matter which entrance you take, you walk straight

towards the most imposing building. From here, the tour starts

counterclockwise across the site (see overview map):

At the center of the Chichén Itzá temple complex is the large

step pyramid known as the Castillo (Spanish for "castle,

palace"). The thirty meter high structure has four staircases on

all sides for access. It is speculated that the length of the

year of the Maya is encoded in the steps of the stairs: if all

four side staircases had 91 steps (the ones that exist today are

the result of reconstructions, so this number is not certain;

also, the terrain is not completely flat, why the stairs should

actually have been of unequal length), multiplying this by four

(number of stairs on four sides of the pyramid) and adding the

step in front of the temple – actually the base of the building

– gives the number of days in the Maya year.

The side

surfaces of the pyramid on both sides of the stairs are stepped

9 times. The (roughly) vertical side surfaces of the steps are

connected at the top by a horizontal band, the larger part

consists of a pattern of four rectangular surfaces worked out as

if hanging over a slightly recessed smooth outer surface of the

steps. For reasons of space, the rectangular areas become

smaller from step to step, and their number is also reduced in

the last two steps. The corners of the steps are slightly

rounded.

The Castillo bears on its top the temple of

Kukulcán, the snake deity of the Maya, whose name coincides with

the Toltec Quetzalcoatl. The six meter high temple on the

pyramid has a main entrance supported by two serpentine columns

to the north. This leads to a narrow room, taking up the entire

width of the square temple, from which one enters the central

room, the roof of which is supported by two pillars. A

corridor-like space runs around this central space on three

sides, to which entrances lead from the remaining three sides.

The door jambs show Toltec warriors in bas-relief.

Inside

the pyramid hides another, smaller (side length about half of

the later) pyramid, which also has nine steps. However, it has

only one staircase on the north side, accessible through a short

tunnel excavated by archaeologists from the side of the later

staircase (closed to visitors). The earlier temple is simpler in

design than the later one. It has only two rooms of the same

size, one behind the other, of which the rear one can be entered

through the front one. There the explorers found a stone jaguar,

designed in red painted form and jade eyes as a seat, which may

have once served as a throne. The upper facade of this temple

has been partially uncovered and is dominated by jaguars in

procession.

The Castillo is the undisputed crowd puller

at Chichén Itzá. However, it holds this rank not only because of

its impressive structure and size, but also for another reason:

Twice a year, at the equinox and some time before and after, at

sunset one side of the pyramid is almost completely in shadow.

Then only the stairs are illuminated by the sun and the steps of

the pyramid are projected onto them. This band of light finally

unites for a short time with a serpent's head at the base of the

pyramid, thus representing a feathered serpent. There is no

evidence that this impressive effect was immediately interpreted

by the Maya, much less that it was created during the

construction of the Pyramid was intended is part of the

opinions. Other sources say the effect was calculated.

The same applies to an echo, which tourist guides use to impress

tourists: If you stand in front of one side of the pyramid, the

sound is thrown back hundreds of meters and amplified. A

clapping of hands sounds like a pistol shot. The echo inevitably

arises with a sufficiently large, smooth reflection surface.

The Temple of the Warriors, so called because of its reliefs

(which can also be found elsewhere in Chichén Itzá), is a

structure dominating the large platform on its east side. The

building consists of a pyramidal base with four steps and a

large upper surface, about half of which is taken up by the

actual temple building. This has been pushed all the way to the

rear edge, so that a larger free space is created in front of

it.

The top platform of the temple can be reached via a

staircase that was originally reached from the portico in front

of the temple pyramid. Two slightly raised pillars and walls on

the sides show that the roof of the portico reached a little

higher at the stairway. The stairs are closed to visitors. The

outer walls of the pyramid-like base are decorated with

continuously repeating reliefs showing eagles, jaguars and

between them warriors in a half-recumbent position. Their

costume is typically Toltec: the large horizontal nasal plug,

the spectacle-like ornaments in front of the eyes, the knee

straps and sandals tied with large bows, and the spear thrower.

In the open space in front of the actual temple stands one

of the figures known as Chak Mo'ol in the characteristic

semi-recumbent pose. The name Chak Mo'ol goes back to the New

York amateur archaeologist Augustus Le Plongeon from the second

half of the 19th century, who saw in him the image of a Mayan

prince he suspected, he had nothing to do with the rain god Chac

.

The roof of the halls and the interior of the temple

supported pillars made of square blocks of stone. They depict

warriors and eagles that eat human hearts. The entrance to the

temple interior was supported by two feathered serpent pillars.

The protruding parts of the tail supported the monumental wooden

door beam. These serpentine pillars are found in largely

identical form in Tula and are therefore regarded as Toltec.

Inside the temple space, several rows of square pillars,

which have reliefs on all sides, supported the vaulted roof, of

which nothing remains. Against the back wall is a low table made

of stone slabs, which is supported by several dwarf Atlantean

figures on their heads and arms. The outer wall of the temple

has cascades of the masks of the rain god Chac, mostly at the

corners. In the wall surfaces, large areas are filled with a

flat relief of feather tendrils, in the middle of which the

human-bird hybrid, also known from Tula, protrudes fully

plastically from the wall.

On the north side of the

pyramidal base is an archaeologist-made entrance to the earlier

phase of construction of the temple (sometimes referred to as

the Temple of Chak Mo'ol), which is largely the same in

structure as the later one but is shifted somewhat to the north.

For the construction of the later temple, it was filled with

rubble to support the weight of the new building. The pillars of

the earlier temple, which once supported the roof that was

removed during the construction of the later temple, are

decorated with reliefs similar to those of the later temple. It

was uncovered during excavations in the 1930s. The colored

painting of the relief pillars is still intact here, because the

interior was completely filled with rubble during the

construction of the later temple and was therefore conserved. It

shows what all the pillars must have looked like originally.

In front of and along the south wall of the temple pyramid

runs an ornate portico, which extends further to the east and

surrounds a large courtyard on three sides. It is considered

part of the Grupo de las Mil Columnas, "Hall of 1000 Columns".

A columned hall originally covered with Mayan vaults runs to the

south and east of the warrior temple. It has collapsed everywhere

because the wooden beams spanning the spaces between the pillars have

rotted away. The pillars made of square stone blocks that originally

supported the roof are mostly carved on all sides. They show warriors in

Toltec costume and equipment, with depictions of snakes and the bird-man

in the lower and upper registers. A brick bench runs along the rear

walls of the former columned halls, which is interrupted in various

places by a slightly raised and further protruding platform, the outer

wall of which is decorated with bas-reliefs of a warrior procession. The

columned halls are divided into four arms:

West arm, south of the

warrior temple. At the southern end, the west arm bends west and leads

to a small temple.

east arm. It begins just south of the Warrior

Temple and runs east from there until it meets the edge of a karst

sinkhole. There are various buildings with smaller columned halls.

south arm. Actually not a continuous columned hall, but smaller sections

of halls that are in front of other buildings. They start at the end of

the east arm and run south.

north arm. These are the portico in front

of the Temple of the Warriors and a portico to the north of the Templo

de las Mesas, oriented north-south.

It is striking that columned

halls of this density and size cannot be found anywhere else in Chichén

Itzá. The spatial organization and the pictorial program on the brick

platforms and the sides of the pillars indicate the function of the

halls. Because there was a lot of space of the same symbolic quality in

them, large numbers of people of the same rank gathered in the halls.

The depictions of rows of warriors on the raised platforms identify

those assembled as warriors.

The themes on the pillars, namely

warriors and the hybrid bird-human being, confirm this assignment and

provide an ideological reference. Similar (smaller) halls are also known

from Tula and the main temple precinct of Tenochtitlán.

The building is located in the northern part of the southern arm of

the Thousand Columns. It is preceded by a double columned hall on the

west. This building (technical nomenclature 3D5) has undergone several

transformations. Originally it consisted of two rows of rooms at right

angles to each other. The facade is unusually well preserved because the

first building was walled on all sides at a later date in order to build

a small temple on a higher level, to which a stairway led up from the

east (ie not from the Court of the Thousand Columns). The front row of

rooms was demolished for the columned hall to the west and the remains

were filled with stone masonry.

The facade of this early building

is characterized by a high sloping plinth, a smooth lower wall surface

and a central frieze band of three sections, the central one having

continuous decoration. Snake heads protrude from it at greater

intervals. The upper façade surface shows masks (in the form of two-part

cascades) and in between fields with either three rosettes one above the

other or one large rosette. The upper cornice also consisted of three

bands, the middle one of which was decorated in low relief.

The

building is a good example of a style of architecture at Chichén Itzá

that predates that known as Toltec and has ties to the Puuc style.

To the east is a long hall (3D6) formed by six rows of square

pillars. In later times, intermediate walls were built between the

pillars at the eastern end, either to ensure greater stability or to

separate a small space.

To the south of this building is the

actual palace of the sculpted columns. The building is fairly complex:

facing the courtyard is a portico consisting of two rows of columns

carved all around. In the center is an entrance into a narrow room,

access is to a rectangular room behind with two rows of columns. From

there one arrives at square rooms with nine columns both in the south

and in the north.

To the south of the building just described is this temple (3D8),

which has not yet been excavated and restored. Its first description

(and the German name) goes back to Teobert Maler. Structurally, the

building is very similar to the Warrior Temple and the Temple of the

Great Sacrificial Table.

Here, too, there are two rooms one

behind the other on a raised platform with a central staircase on the

west side. The roof was supported by carved pillars. Here, too, the

entrance was formed by two monumental pillars in the shape of a snake.

In the row of buildings on the eastern side of the courtyard are

several buildings that have not yet been uncovered. 3D9 has a columned

hall behind which lies a two-room temple building. Building 3D10

consists of several connected columned halls with considerable internal

area. Here numerous intermediate walls were drawn in between the

columns.

Behind the buildings described here are several smaller

constructions. Of particular importance is the unusually large and

elaborately constructed sweat bath (Temazcal), as several smaller sweat

baths in the Court of the Thousand Columns are tiny in comparison. The

building has a small portico of four columns with benches at different

heights along the back wall. From there a low passage leads into the

actual sweat bath, a rectangular room with a low stone vault and a niche

at the back.

To the north of the sweat bath is a medium-sized

ball court (3E2), from which only the side walls of the reflective

surfaces have been uncovered. They show warriors or ball players with

large feathered headdresses in a less precisely executed bas-relief that

used to be modeled over with stucco.

To the north of the Warrior Temple is a temple excavated in the 1990s (the first excavation attempts go back to Teoberto Maler, who also coined the German name), which is very similar in shape to the Warrior Temple, including its temple building, but is somewhat smaller. An earlier temple building with well-preserved, colorfully painted relief pillars was also found inside this pyramid base, which is not accessible. There is no colonnade in front of the temple, it extends in smaller dimensions to the north on its side.

Venus Platform and Platform of the Skulls or Wall of the Skulls is situated not far from El Castillo. These two structures were religious points where people were sacrificed. Tzompantli (originally a Toltec word) is believed to be a place for sacrifices after the Ball court games. It is covered rows of carvings of human sculls. Venus Platform is not far is also covered by grim reminder of the past. Although it was originally covered by paintings blood from the killings covered over the whole altar. It is not very high, but it is also prohibited from climbing. You can do it quickly if you want, even if you get caught no one will throw you out.

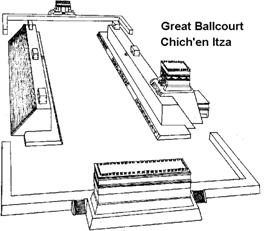

At least twelve ball courts have been found in Chichén Itzá. The

Juego de pelota on the large platform represents the largest and most

important of more than 520 ball courts of the Mayan culture. It is

located approximately one hundred meters northwest of the Pyramid of

Kukulcán. The playing field is 168 m long and 38 m wide. The shape of

the playing surface is reminiscent of two "T's" placed against each

other, it is flanked by walls eight meters high, from which the ball

bounced back into the playing field. The walls are unusually thick. From

the outside, stairs led to the surface of the walls over almost the

entire length, they have not been reconstructed. Because of the limited

space on the walls, the ball game could only be watched by a limited

number of people. In front of the walls was a wide base over the entire

length and slightly beyond, the front edge of which was beveled. Long

relief scenes are attached here in 6 places.

The “Big Ball Court”

at Chichén Itzá was (because of its dimensions and the height of the

target ring) hardly really usable for the ball game, but rather intended

for ceremonial purposes and probably served to represent political and

probably also religious power.

In ball games, the ball had to be

played without using the hands and legs, only the shoulders, chest and

hips were allowed. The ball was made of rubber, was solid and weighed

about 3 to 4 kg. Pictures show the protective clothing worn by the

players. It was made of hardened leather, and wooden reinforcements were

also attached. In addition, some of the players wore two different

shoes. One of them had ankle protection so that the player would not

injure himself when throwing to the ground (to reach the ball running on

the ground with his hip). An iron-shaped object made of wood served as

support and protection for the hands. Colonial accounts of the Aztecs

tell us that a game rarely ended without major injuries; bruises in

particular were extensive and treated surgically.

The object of

the game, in its Late Classic and Post Classic versions, was to shoot

the ball through one of the two rings attached to the reflex walls.

Since the openings were not much larger than the ball, this should only

very rarely have succeeded. The height at which the rings were installed

was another complication for the “Big Ball Court” at Chichén Itzá.

Many of the ball courts at Chichén Itza feature reliefs. On the ones

at the "Big Ball Playground", which are repeated six times, it can be

seen that someone has been beheaded. The blood gushing out of the torso

of the decapitated is represented in the form of seven snakes, which the

Mayas used as a symbol of fertility. From the blood that spills on the

ground grows the "Tree of Life". This depiction is based on a Mayan myth

that describes the origin of the game. According to the current state of

knowledge, the representation does not allow any conclusions to be drawn

as to whether winners or losers lost their heads, or whether the

representations are to be understood more symbolically.

Many

details of the ball game are no longer known today, some being inferred

from analogies with the better known Aztec conditions. Because of this

deficiency, many nonsensical ideas entwine around the ball game in

particular. Tourist guides at Chichén Itzá demonstrate that if you clap

your hands anywhere in the square you will get a multiple echo, which is

inevitable on large flat surfaces. It is the imagination of the guides

that the cause of this echo is the construction of the side walls from

seven different types of limestone and sandstone, since the building

material is basically uniform and sandstone is not found anywhere in the

Yucatan. In addition, the material of the surfaces has no effect on echo

effects.

The religious and symbolic importance of the large ball court is emphasized by the temples located within its walls.

Most important and conspicuous is the Temple of the Jaguars, which

stands on the southern end of the ball court's eastern side wall, which

at this point has been extended into a pyramidal base. Only a narrow

side staircase leads up to the temple (closed today). The temple is

oriented towards the inside of the ball court. The entire construction

shows the struggle of the Maya with the limited space available for the

temple: the building platform supporting the temple is only a little

smaller than the pyramid base. As a result, only a narrow strip of flat

space remains in front of the building platform. This strip stands in

odd contrast to the approach stairway, which runs almost the entire

width of the temple.

Access to the interior of the temple is

through a wide entrance supported by two very thick serpentine pillars.

The serpents' tongues protrude far from their mouths. The vertical body

of the snake is bent twice forwards and then upwards and encloses the

door beam with the snake rattle. The temple has two parallel rooms one

behind the other. Its walls today bear heavily faded murals. Early

copies show battles between a large number of warriors on the outskirts

of a village where people still seem to go about their daily activities

undisturbed.

The design of the facade is the most complex and

richest of Chichén Itzá: the lower wall surface, which consists of

several sunken areas, in which there is no decoration, follows on a

sloped base. Four wide bands follow from bottom to top with the

following motifs: the bottom band is smooth, the one above shows, like

the fourth, two intertwined feathered serpents. Most impressive is the

third band, which depicts a continuous procession of jaguars. Between

each pair of jaguars is the depiction of a shield whose plumage falls

over the two lower bands. Towards the top, after a smooth band, there is

a zone with angular coiled feathers. Between the whorls there are three

concentric discs in the lower row, and three hourglass-shaped columns in

the upper groups. The intertwined feather serpents follow for the third

time. The facade, which reaches a height of eight meters, is closed at

the top by the usual large, slightly inclined stone slabs.

The

entrance side of the temple is reconstructed, only the bases of the

walls and the lower parts of the serpentine pillars were in situ.

The lower temple of the Jaguar Temple consists of a rectangular room.

He stands below the Jaguar Temple on the outer wall of the pyramid base.

The entrance is formed by two pillars and therefore has three openings.

The pillars and the side wall pieces next to the passages have

bas-reliefs. A jaguar throne stands in the central entrance.

This

temple also has (like the north temple) a bas-relief covering all the

walls in several registers, which was originally painted in color

(remains are still preserved in the corners). The painting with a red

background for better recognition is modern (by the archaeologist Erosa

Peniche). The content of the relief apparently depicts historical scenes

in which important individuals in rich attire are associated with

hieroglyphic symbols that do not belong to the canon of the Mayan

script.

The facade design is a combination of the Puuc style

(upper half of the wall with three-fold horizontal bands) and sloping

lower part of the lower wall surfaces, as they are characteristic of

central Mexico. The front part of the vault and the corresponding facade

have been reconstructed.

The North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded, is a small building on the north end wall of the Ball Court. It consists of a single room, to which an entrance with two columns leads. The stringers of the access stairs depict a tree whose roots emerge from the earth monster. The interior walls of the room, including the partially preserved vault, are decorated with a roughly executed bas-relief similar to that of the Lower Temple of the Jaguars. Here, too, the colored contouring is modern.

The South Temple is actually a single 25 meter long room open to the ball court with a series of 6 sculpted pillars. The pillars show the usual theme of warriors in Toltec warrior gear standing on the depiction of a bird-man. The figures are identified by characters outside of the Mayan hieroglyphic tradition. The building is poorly preserved, the side walls are partially reconstructed.

Not far from the eastern side of the Great Ball Court is a platform

which, because of its bas-relief decoration, has in modern times been

given the Náhuatl term tzompantli. This word designates platforms on

which was erected a wooden framework to which the skulls of sacrificed

persons were attached, as has been amply described for Tenochtitlán and

contemporarily illustrated.

The Chichén Itzá Tzompantli is a

large T-shaped platform, just over 1.5 meters high. The vertical outer

walls of the platform are covered with four rows of skulls in three

registers, with the wooden posts also being depicted. The square portion

projecting eastward from the block of the Tzompantli proper resembles in

many details the two platforms described below. The decor here shows as

a central motif a sequence of warriors between oversized eagles, which

are holding human hearts in their claws in order to eat them. An

uninterrupted sequence of relatively short snakes is depicted in the two

frieze bands, while the top band shows large feathered snakes whose

heads protrude fully three-dimensionally at the corners.

The Venus Platform is to the north, not far from the Great Pyramid.

Like the platform of the eagles and jaguars, the construction consists

of a square block of masonry with stairs leading up to it in the middle

of all four sides.

The bas-relief visible in the raised and

sunken fields of the side surfaces shows, among other things, the

human-bird hybrid en face. Next to it is the symbol of the planet Venus,

connected to a bundle of rods, from which the so-called Mixtec

year-bearer symbol protrudes at the top as an indication of a

calendrical function can be seen. The steps of the platform are flanked

by one of the snake heads. These snake heads are the plastic ends of a

band of snake bodies that wrap around the platform in the top register.

A platform with an almost identical image program is located immediately

east of the Osario.

The smaller of the two structurally identical platforms is immediately adjacent to the southeast corner of Tzompantli. The subject matter of the bas-reliefs is similar but not the same, there are no depictions of the sign of Venus. Instead, eagles and jaguars are repeatedly depicted holding human hearts in order to eat them. Eagles and jaguars were names for warrior associations among the peoples of central Mexico. One can assume that the same ideas existed behind the depictions on the Toltec-inspired buildings at Chichén Itzá. The stairs on the four sides end at the top in fully plastic snake heads, the feathered body of the snake is indicated in very flat relief on the stair stringers.

The path to Cenote Sagrade cuts through the wall surrounding the northern precinct, which is very high above the surrounding terrain due to the height of the platform. Columns were discovered on the inside of the wall during the passage to the cenote, which may have supported a roof leaning against the wall. The function is unclear, it has been assumed that they were market stalls. The wall is broken through in eight places by a gate construction, which ends in a sacbé leading to the outside.

Temple of the High Priest or The Tomb of the High Priest (El Osario). This is the first notable building after leaving the platform in a southerly direction. Here you are, so to speak, in the old town of Chichén Itzá. At first glance, the Pyramid of the High Priest looks like a small copy of the Pyramid of the Kukulcáns. The pyramid is a four-sided step pyramid with a stairway on each side with snake heads at the bases. But a closer look reveals some differences. First there is the temple at the top of the pyramid, which, similar to that of the warrior temple, has an entrance flanked by two erect serpents. Inside is a sacrificial table carried by small men. Inscriptions from the year 998 AD were found here. found. If you look further on the facade of the pyramid, in contrast to the simple design of the Kukulcán pyramid, reliefs and ornaments in the Puuc style can be seen here. In the top row you will find a snake body relief, which ends in a sculpture of a snake head in the pyramid corner. Below you can see some representations of fantastic bird creatures. Incidentally, the name of this structure is a creation of archaeologist Edward H. Thompson, who found a shaft in the pyramid that led to a natural cave with a tomb. What is remarkable about the building is the building fragment on the southern flank. This was created from the stones lying around the temple and depicts four Chaac masks (depictions of the rain god) lying one on top of the other.

The Nunnery (Las Monjas). This building has been extended over the years until it reached this impressive 25 meter wide. The larger main building is kept relatively simple, but the smaller eastern part is richly decorated. Particularly noteworthy is the gate in the eastern part. Among other things, there are twelve Chaac masks on the front and the corners. Furthermore, above the door is a depiction of a ruler sitting cross-legged with elaborate feather headdress. This depiction of a ruler is framed by an oval ornament. By the way, the name of the building is based on a fable of the first Spanish soldiers who saw this building. The soldiers assumed that this is where virgins spent their lives before being sacrificed. This building probably had more of an administrative purpose.

The Church (Iglesia). The building is in the immediate vicinity of the nunnery and that is where the name comes from. The Spaniards simply assumed that a monastery also had a church. The building with only one entrance and one room has an almost tower-like overall structure. Noteworthy is the lower part, which is kept very simple without any stucco. There are numerous openings in the wall above this section, which suggests that cloths or something similar may have been attached here in the past. The richly decorated upper part begins above this section. The central element is the middle band, which shows some Chaac masks on the front and the corners. On the obverse, between the masks, there is an armadillo and a snail on the left and a tortoise and a crab on the right. The building is crowned by a roof comb, which in turn receives some Chaac masks. In general, the building is considered one of the best preserved of the classic Puuc style.

El Caracol is Spanish for “snail” given to this building due to its architectural appearance. The snail tower is indisputably the highlight in the southern part of the complex. As early as 1842, Frederick Catherwood captured the beauty of this building with its architecture, which is unique in the Mayan world. There is another platform on a basic platform with a wide staircase. Finally, a tower is erected on this, which has it all. Four entrances lead to the interior, and a narrow spiral staircase leads up. Due to its snail shape, it is also the namesake for the entire building. The tower is probably intended for observing astronomical data. The alignment of the three windows that have been preserved indicates this in any case. Only on certain days do the rays of light shine through all the windows for a few seconds to meet at a defined point. A smaller platform with columns is in front of the building. Unfortunately, this building, like all the others, has not been accessible since 2004.

About four hundred meters just north of the Pyramid of Kukulcán lies the impressive Cenote Sagrado, in English the "sacred sinkhole" (natural "well") with an almost circular shape and vertical walls. Chichén Itza got its name from him, namely Fountain of the Itzá. Edward Herbert Thompson made underwater surveys here between 1904 and 1910. More recent investigations took place around 1960, which brought many thousands of finds to light. Large amounts of objects were found at its bottom, including jewellery, jade, gold and various ceramics. In addition, more than fifty skeletons were recovered. According to the report from the 16th century known under the name of the Bishop of Yucatán Diego de Landa, these are interpreted as human sacrifices, which is also supported by the entire find constellation. At the edge of the sinkhole is a small temple building.

Ruins of the Mayan Steam bath are situated in the far corner of Chichen Itza. It is not particularly big or incredibly impressive. However in the past it played an important role in a pagan religion of the Mayans. It served as a type of a religious ceremonial sauna. Priests and anyone who participated in the ceremony came here to cleanse themselves from filth. They came to this small building to achieve that. A small entrance to the structure meant that people had to crawl here on all fours to get inside. Once inside high temperature caused men to sweat. Dirt was scraped from the skin by participants of the ceremony. Parts of the roof today have collapsed so it is easier to get inside than before.

Sacbe is an religious ceremonial road that is common not only in Chichen Itza, but throughout a Mayan World. Mayans didn't choose the easy route when they had to construct their paths of communications. Instead of making paths on the flat ground and covering them with slabs, Mayans actually created long narrow platforms made of stone and mortar. Once these structures were completed road were laid on top of these platforms.

Of course, visiting the ruins is the focus here. Unfortunately,

no more buildings can be climbed here. But with 8,000 visitors a

day, this is perhaps also urgently needed to protect the

building and is therefore understandable. Although this reduces

the sense of adventure to the ambience of an open-air museum,

the facility is still unparalleled from this point of view. The

only thing that bothers here are the other 8000 tourists. It is

therefore strongly recommended to stay overnight here in order

to visit the facility early in the morning before the arrival of

the cruise tourists (from 8:00 a.m. to around 11:00 a.m.).

The facility is in the middle of the dry Yucatán rainforest.

Therefore, fauna and flora have a lot to offer. Especially early

in the morning you can see one or the other bird on the still

relatively empty facility. The cenotes in particular are popular

with birds as a source of water and food. And, of course, this

facility also seems to belong more to lizards than to humans. At

least these are the only ones currently allowed to climb the

pyramids alongside the archaeologists.

There is a very

special highlight every evening. Then the northern part of the

complex (including El Castillo and the large ball court) is

wrapped in colored light in the form of a light show. There is

music and the story of Chichén Itzá is told. The whole thing can

also be enjoyed in German via a borrowed receiver with

headphones. Incidentally, the entrance fee for the light show

will be credited to the visitor if they visit the facility the

next day.

Finally, of course, when the sun is burning and

the temperature is high, bathing fun is in the foreground.

Therefore, many hotels have a pool on offer. However, if you

cannot fall back on this luxury or are looking for an

alternative, you should definitely visit the Ik Kil Parque

Ecoarqueológico (see Sights).

By plane

There are two international airports nearby, Mérida

and Cancun, with Cancun being served more frequently during the

season.

In the street

There is no major official ADO

bus station here, but ADO/Oriente second class buses between

Merida and Playa del Carmen stop in the parking lot in front of

the main entrance. From Playa del Carmen there is a first class

ADO bus at 8am from Terminal Touristica, as well as several 2nd

class buses (from Oriente, are about half the price but take 1

hour longer) from Terminal alterno.

For onward travel to

Merida/Cancun, a bus stops every hour in front of the market at

the exit. There are also collectivos for the trip to Valladolid.

By boat

Although the town is inland, almost every cruise

ship stops in Cancun, from where passengers are loaded onto

buses bound for Chichén Itzá.

The complex itself can only be explored on foot, which is also quite possible. A hat, sunscreen and water should be part of the equipment, as there is not shade everywhere. Even if you are not allowed on the pyramids here, good shoes are recommended. If you have to get from the car park and bus stop to the hotels on the site or the side entrance without buying an admission ticket, the route leads completely around the site. Especially with the warm temperatures, it is not advisable to walk along the main road. The only alternative, however, is a taxi, which costs around €5 for the relatively short journey.

Anyone entering the facility should have stocked up on water

beforehand. If you have forgotten this, you can buy a few

bottles of water at the kiosk at the high priest's grave at a

"preferential price". There are also toilets and a few souvenirs

here. However, if you are looking for souvenirs on the site, you

should wait until the cruise tourists (around 11:00 a.m.) show

up. By then, numerous Maya from the area have set up their

stalls along the Sacbé to the sacred cenote and on the

connecting path between the High Priest's Tomb and Caracol and

are selling everything that can be provided with the lettering

Chichén Itzá or the picture of El Castillo. Of course, there are

more shopping opportunities at the main entrance and side

entrance. On the latter, the souvenir shop at Hotel Mayaland

also has a good selection of international literature.

There are small shops at the hotels for stocking up on groceries

and daily needs. But it is certainly cheaper in Pisté, about 5

km away.

Hotels Mayaland and Hacienda Chichén offer a large buffet for tourists every day. The tour guides on site often take their groups here. Dancing is provided for entertainment at Mayaland over dinner and singing at the Hacienda. While the buffet isn't much of an enlightenment, it's okay and always fills you up. If you don't like the constant coming and going of tourist groups or simply value the food more, you should either go to the more expensive restaurants of these hotels or make your way to Pisté. Another option for participating in a large buffet is the buffet at Ik Kil Parque Ecoarqueológico. Although this is 3 km away, it offers additional bathing fun and a fantastic ambience (see sights).

Chichén Itzá offers the rare opportunity to stay overnight at

the archaeological site. This is a bit more expensive but very

comfortable and worthwhile.

Hotel Mayaland (100 meters

from the side entrance). Tel: +52 985 851 01 00. The hotel has

been here since 1923 and is not exactly an attraction from the

outside. But the huge garden is intoxicating. Winding paths lead

through a very well maintained park past pools and smaller

pyramids or platforms from Chichén Itzá to the hotel bungalows.

In the main building there are the slightly cheaper normal

rooms, while the bungalows are slightly more expensive. But

lying at the foot of a pyramid by the pool costs something. All

rooms are very well maintained and stylishly furnished. There is

a private entrance from the hotel grounds to the central area of

Chichén Itzá. Price: double US$110 to US$144.

Hacienda

Chichén (300 meters from the side entrance). Tel:

+52-985-851-0045, Fax: +52-985-851-0046, Email:

info@haciendachichen.com. Originally this facility was used by

archaeologists. Even Edward H. Thompson is said to have stayed

here. Various awards underline the beautiful complex with a good

library, art shop and a short distance to the central area of

Chichén Itzá. Price: double US$ 129.

Hotel Villas

Arqueologicas (300 meters from the side entrance). Tel: +52

(985) 856 6000, Fax: +52 (985) 856 6008, Email:

reservas@villasmex.com. Price: double room US$70.

Hotel

Dolores Alba, Calle 63 No. 464 × 52 y 54, Mérida, Yucatán,

México 97000 (2km away). Tel: +52 (999) 928-56-50, Fax: +52

(999) 928-31-63, Email: info@doloresalba.com. A little further

from the central area, this green property offers a free

delivery service. Price: DR MEX$420.

If you like it

cheaper and a little simpler, you should accept a morning

journey of 5km. Here is the village of Pisté, which can serve

with about 20 different accommodations. Here is a small

selection:

Piramide Inn Resort, Calle 15 A #30x20, Km. 117

Carrer. Merida-Puerto Juarez, C.P. 97751 Runway, Tinum, Yucatan,

Mexico. Phone: +52 (985) 85-1-01-15, Fax: +52 (985) 85-1-01-14,

Email: sylvia@wohlmut.com. Also offers camping facilities.

Price: DR MEX$450.

Hotel Chichén Itzá, Calle 15ª No. 45

Runway, Tinum, Yucatan, Mexico, 97751.

Posada Olalde, Calle

66 runway Yucatan Mexico. Tel: (0)19858510086, Email:

volalde_ucan@hotmail.com. Price: MEX$250.

Grand Mayab Hotel &

Bungalows, Calle 15ª No. 45 Piste, Tinum,Yucatan, México, 97751.

(Carretera Federal Valladolid - Chichen Itza Km. 140 Kaua,

Yucatan, Mexico.). Tel: +52 985 808 1773, Email:

reservaciones@grandmayab.com. Price: $72.

When visiting the facility, it is essential to ensure sufficient

sun protection in the form of a hat and sun lotion. Shade is

scarce in the central area. Of course, it goes without saying

that you should provide yourself with enough water before the

visit.

Otherwise, the general guidelines for southern

Mexico apply. A good insect repellent should protect against

mosquitoes. In addition, some precautions should be taken:

Malaria prophylaxis should be carried at least for

emergencies.

A typhoid vaccination should be carried out

beforehand.

Hepatitis A, B, tetanus and rabies vaccinations

should be refreshed.

At the entrance you can book local guides, some of whom can also speak English or German. The cost for a 2-3 hour tour is around US$ 40.00. The larger the group, the cheaper.

According to the official archaeological delimitation, the area

of Chichén Itzá covers around 15 square kilometers and extends

to the outskirts of the small town of Pisté in the west. The

density of development in this area is uneven: areas with

relatively close-knit buildings made of stone masonry of

different construction techniques were located on platforms more

or less elevated above the surrounding terrain, some of which

were surrounded by low walls. These are always surrounded by

zones that are as good as undeveloped. They will have been used

for cultivation to supply the population, but this cannot be

proven in detail.

The flat and stuccoed platforms were

the primary traffic areas within each group. More than 70

sacbéob, brick streets, have been identified at Chichén Itza to

connect the built-up areas with each other and the center.

Of particular importance were the numerous funnel-shaped

collapse sinkholes (known locally as "rejolladas") that did not

reach groundwater level. Because of the sheltered location and

the special temperature conditions, plants (e.g. cocoa) could be

grown in them that would not thrive on the more or less flat

terrain, as is still the case today.

The water supply was

mainly based on the two water-bearing sinkholes (the "sacred

cenote", which was perhaps not used for the secular water

supply, and the Xtoloc located near the center) and on a few

cisterns (chultun). In a doline collapse near the Chichen Viejo

group, a wide brick well from ancient times was archaeologically

uncovered, which may have ensured the water supply of the area.

Despite attempts to reconstruct a story, Chichén Itzá is

essentially famous for its architecture. The different building

types and stylistic forms continue to be one of the most

important sources of information about the history of the place.

Here, different types of buildings catch the eye, which can be

distinguished according to their floor plan. In addition, there

are construction details and forms and techniques of the facade

decoration that are characteristic of the respective building

type. The differentiation of the buildings into three successive

phases, namely Maya, Toltec and Maya-Toltec, introduced by the

researchers of the Carnegie Institution according to these

aspects, is no longer maintained in this way today. The function

of many buildings has only been partially clarified.

Only

well-preserved and mostly restored buildings are mentioned here

as examples of building types (many more are hidden in the dense

forest and have not been uncovered):

Pyramid structures with

stairs on one or four sides, at the top a temple building, some

with a hall-like interior. Examples: Castillo, Osario. The

function was mainly religious.

Temple with a hall-like

interior on a multi-level high platform. Examples: Warrior

Temple (Templo de los Guerreros), the two temples of the large

and the small sacrificial table, Templo de la Fecha.

ball

courts. Examples: Large ball court, ball court east of Casa

Colorada, ball courts in the Thousand Column Complex. The

symbolic function of the ball game is disputed.

columned

halls. Example: Numerous porticos in the Thousand Column

Complex. Function: According to the reliefs, they served to

gather large numbers of people of equal rank, especially

warriors.

Courtyard galleries with colonnaded courtyard and

portico. Example: Mercado, others etc. in the Grupo de la Fecha.

function uncertain.

Buildings with rows of interiors,

according to the Puuc tradition. The rooms are arranged in one

or two parallel rows, transverse rooms at the ends are common.

Example: Casa Colorada, Casa del Venado, Akab Dzib, Las Monjas,

Temple of the Three Lintels. Function: Administrative center or

official residence of a noble line.

Buildings with numerous

interiors with a complex layout and enclosed courtyards.

Example: Casa de los Caracoles in the Grupo de la Fecha,

buildings immediately east of the Monjas. Function: Official

residence of a noble line.

Low square platforms with four

flights of stairs. Example: Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars

and Venus Platform, Platform in front of the Osario. A ritual

function can be assumed.

Large platforms with surrounding low

wall and gateways. Example: Big Platform, Grupo de la Fecha. The

function of the wall is not military, but serves to demarcate

zones that were not or only partially accessible to the public.

Sacbés (brick streets) connecting the different groups of

buildings, about 70 have been located so far. Function: Since

vehicles were not known and could not have been used because of

the intermediary stairs, the streets served for processions and

symbolically expressed relationships between the connected

zones.

The names of some structures date back to the

colonial era, but most are of more recent origin and describe a

distinctive architectural feature. German names are only given

here if they are established. Most structures, however, do not

have such a name, many being identified only by the quadrant

(from the Carnegie Institution map) and in these by a serial

number.