Chichén Itzá is one of the most important ruins on Mexico's Yucatán

Peninsula. It is located about 120 kilometers east of Mérida in the

state of Yucatán. Its ruins date from the late Maya period. Covering

1547 hectares, Chichén Itzá is one of the most extensive sites in the

Yucatán. The center is occupied by numerous monumental representative

buildings with a religious and political background, from which a large,

largely preserved step pyramid protrudes. Ruins of upper-class houses

are in the immediate vicinity.

Between the 8th and 11th

centuries, this city must have played a nationally significant role.

However, it has not yet been clarified what exactly this looked like.

What is unique is how different architectural styles coexist in Chichén

Itzá. In addition to buildings in a modified Puuc style, there are

designs that show Toltec features. In the past, this was often

attributed to a direct influence of emigrants from central Mexico or

conquerors from Tula. Today one tends to start from diffusionist models

and assumes that different stylistic forms are largely simultane- ous in

the monumental buildings.

The development of tourism in the

Yucatán has made Chichén Itzá the archaeological site that attracts the

most visitors in Mexico after Teotihuacán. Chichén Itzá was declared a

World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988. On March 30, 2015, the memorial

was included in the International Register of Cultural Property under

Special Protection of the Hague Convention for the Protection of

Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.

The city's name comes from the Yucatec Maya and means "at the edge of

the well of the Itzá". It is composed of the three words chi’ (“mouth,

rim, bank”), ch’e’en (“well” or “cave with water”) and itzá (the

people’s own designation).

The "fountain" in the name of the city

meant the water-bearing doline (cenote), which is now known as Cenote

Sagrado. Chichén Itzá is situated on a very uneven karst terrain with

generally but little elevation change, dotted with many collapse

sinkholes (known locally as rejolladas); these usually do not reach the

groundwater horizon, but offer favorable conditions for planting for

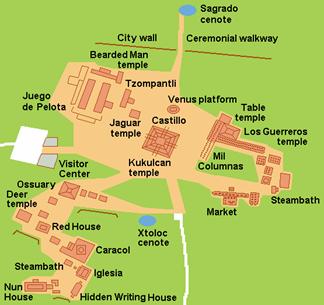

microclimatic reasons. One water-bearing doline is located north (Cenote

Sagrado) and south (Cenote Xtoloc, next to the small temple of the same

name) of the center. It is certainly no coincidence that the ceremonial

center lies exactly between these two cenotes.

Another name given

to the city before the arrival of the Itzá is mentioned in Chumayel's

Chilam-Balam. How this name - Uuc Yabnal - is to be understood has not

yet been satisfactorily clarified.

In 1533, almost ten years before the Spanish had completed their

conquest of the Yucatán, Francisco de Montejo the Younger established a

small settlement in the ruins of Chichén Itzá called Ciudad Real. So

far, no archaeological traces have been found of the simple dwellings

built at that time. The settlement was besieged by the Maya and could

not be held. Diego de Landa (who was not there himself at the time)

reports that the pressure was so great that the Spaniards could only

withdraw secretly at night. Landa, who came to the Yucatán in 1549,

gives a fairly detailed description of some of the buildings in the

center of Chichén Itzá - namely the castillo and the two small platforms

- as well as the wide road to the sacred cenote and objects he found

there. A brief note of his visit to the ruins on July 26, 1588 was left

by Antonio de Ciudad Real.

Early modern descriptions and research

Among the earliest modern visitors was Baron Emanuel von Friedrichsthal,

in 1840, then first secretary of the Austrian legatee in Mexico. He also

took up daguerreotypes, but was unable to publish his report. In 1841,

John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood stayed at Chichén Itzá for

a long time, preparing detailed descriptions and drawings. Stephens'

accounts brought the Central American ruins, including Chichén Itzá, to

the attention of those interested in North America and Europe. They

encouraged, among others, the French Désiré Charnay to undertake

research trips. He visited Chichén Itzá in 1860 and took numerous

photographs there.

The New York amateur archaeologist Augustus Le Plongeon undertook the

first excavations in 1875. However, the historical depictions that he

extensively presented in his works belong to the realm of the

imagination. He was followed in quick succession by Teoberto Maler, who

left only sparse records in addition to photographs, and the Englishman

Alfred Percival Maudslay, who devoted six months to the ruined city. The

American diplomat Edward Thompson bought the hacienda on whose grounds

Chichén Itzá is located in 1894 and conducted research there until the

1920s. Among other things, he dredged from 1904 the deposits in the

sacred cenote, where he also undertook diving expeditions. He was

accused of illegally taking numerous valuable objects out of the

country, but these charges were later dropped as unfounded.

Beginning in 1924, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, under the

direction of Sylvanus Griswold Morley, carried out excavations and

reconstructions in cooperation with Mexican government agencies.

Carnegie Institution archaeologists (including Eric Thompson) worked on

ruins at the great platform (particularly the Temple of the Warriors),

at the Caracol, the Monjas and the Mercado, and at the Temple of the

Three Doorbeams far to the south. Restoration work has been carried out

by archaeologists from the Mexico Antiquities Authority on the Castillo,

the Great Ball Court, the Tzompantli, the Platform of the Eagles and

Jaguars, and the Platform of Venus. The extensive excavations of the

Carnegie Institution in Chichén Itzá laid the foundation for the

chronology of the entire northern Yucatán based on the pottery found.

Carnegie Institution scholars also developed the view that Chichén Itzá

was where the cultures of native Mayans and immigrant Toltecs met, as

evidenced by different architectural styles. The Carnegie Institution

and later the Mexican INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e

Historia) also carried out a precise mapping of Chichén Itzá, which

covers many times the area accessible to tourists today.

Recent

excavations and restorations by the INAH since the 1980s (mostly under

the direction of the German Peter J. Schmidt) have focused on follow-up

investigations and consolidations in the center of Chichén Itzá

(completion of the Castillo, the Temple of the Great Sacrificial Table,

the eastern part of the Thousand complex of columns, Osarios) and new

excavations in the south (entire Grupo de la Fecha). In 2009, new

excavations began around the castillo under Rafael Cobos.

The history of ownership of Chichén Itzá is unusual and has had a not insignificant impact on exploration and conservation: after Edward Thompson's death in 1935, his heirs sold the hacienda to the influential Yucatec Barbachano family since the 19th century, who now run two hotels there . Although the Chichén Itzá site has been officially declared an archaeological site and is effectively federal territory (zona federal), this has had no consequences under private law. In March 2010, the last owner, Hans Jürgen Thies Barbachano, sold a portion of the 80-hectare Chichén Itzá site, which includes the most important buildings of the old city, to the Yucatán government for 220 million pesos (about 13 million euros ). On the site of the old town there are not only several hotels, but also settlements of the local population.

There are three different types of information sources for the

history of Chichén Itzá, each of which sheds light on different topics:

the archaeological findings from excavations and recording of surface

finds as well as measurements

The inscriptions in the hieroglyphic

writing of the Maya

The Written Accounts of the Aftermath of the

Spanish Conquest

It is not uncommon for information from the

three types of sources to be inconsistent, and to a significant degree

even contradictory, because they arose in different situations.

Archaeological evidence is the unintended result of human life and

therefore not consciously altered or focused. However, the uneven

chances that traces from different areas of life are reflected in

material finds and the preservation conditions in the soil act as a

filter through which only parts of the past reality of life are

recognizable. Contemporary written monuments, on the other hand, are

subject to a different thematic selection: here it was the local rulers

who had themselves and their dynasties and their deeds carved in stone

for their own glorification. The third group of sources, written

centuries after the events recounted, are shaped by the perspective of

their authors and the intentions behind the writing. Here the texts of

Spanish clerics and those of Indian village scribes differ

fundamentally. In addition, the authors' different access to the

information and the unavoidable distortions to which they were already

subjected play a decisive role.

Archaeological Sources

According to the types of pottery found, Chichén Itzá has a settlement

history of almost two thousand years. However, buildings can only be

proven for the late classical period around 750 AD, which corresponds to

the cultural development in the Puuc style further to the southwest.

This was followed by different building forms in the End Classic that

were associated with Toltec influence or even the presence of emigrants

or conquerors from Tula until the 1970s. During this time, the buildings

on the Great Terrace with the ball court, the Castillo, the Warrior

Temple and the thousand-column complex up to the so-called Mercado were

built, but also in other parts of the city, which has meanwhile grown

enormously. Today it is assumed that the monumental buildings belonging

to the “Toltec” and a modified Puuc style were largely contemporaneous.

How the sometimes striking stylistic similarities between Tula and

Chichén Itzá can be explained historically has not yet been resolved.

Chichén Itzá directly ruled over a smaller area, as shown by the

inscriptions in nearby sites. It is believed that Isla Cerritos served

as the port for the commercial activities discernible in materials from

the north and central Mexican highlands, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and

western Panamá. In the Postclassic, the city was slowly depopulated and

visited only by pilgrims who brought offerings, as is also documented in

many other places.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions with dates

The

following summary of dates in hieroglyphic inscriptions from Chichén

Itzá and the nearby sites Halakal and Yula is based on a list provided

by Nikolai Grube and has been updated. It shows that hieroglyphic

inscriptions (with two exceptions) only exist for the very short period

of around 60 years.

All Long Count dates in square brackets are

calculated. The notation of the dates on the monuments is either

exclusively as a calendar round or exclusively or additionally in the

notation "tun [number] in the k'atun ending with the day [number] ajaw".

The k'atun 1 ajaw is expressed in the Long Count as 10.2.0.0.0.

Chilam Balam Books

Of the 17th- and 18th-century Yucatán

village books known collectively as the Chilam Balam books, three

(named after the places where they were found, Tizimín and Chumayel,

and the Codex Pérez) contain chronicle-like listings of years in the

form of k'atun [number] ajaw. These annual figures include

keyword-like, often unclear statements about events. Since the 13

possible names of the k’atun, which lasted almost 20 years, are

repeated after around 256.27 years, no clear statements of time

within a longer period of time are possible. Therefore, when

determining European dates, other aspects must also be taken into

account, which change with the progress of research. The

contradictions between the chronological order in the various

sections of the Chilam Balam texts lead to further problems of

interpretation. The Chilam Balam books also still contain prophecies

in which events are linked back to k'atun dates. These events are

partly reflections of historical events and can possibly be used to

elucidate them.

Spanish Writings of the 16th Century

The

most important source is the report of the Franciscan and later

bishop Diego de Landa (only preserved in a later, probably heavily

edited copy). Information is also provided by the 50 Relaciones

[geográficas] de Yucatán, reports from 1577 to 1581 based on an

official questionnaire on all aspects of the country, written by

local administrators using indigenous informants. For parts of the

Yucatán, many of the reports are based on information from the Mayan

chronicler Gaspar Antonio Chi and are therefore not to be considered

independent of one another. Works by other mostly Spanish authors

contain only a few details.

The reconstructed history differs fundamentally depending on the

source used. While the hieroglyphic texts offer the self-representation

of a small section of a ruling dynasty, the colonial and later written

texts consist of largely unconnected, brief individual reports that can

only be combined to form questionable representations. Overall, most of

the history of Chichén Itzá remains (and probably will remain) unknown.

History according to hieroglyphic inscriptions

The inscriptions

only cover a relatively short period in the history of Chichén Itzá,

essentially a ruling family, particularly its important exponents.

According to the inscriptions, Ek Balam, which was clearly oriented

towards the core area of the Classic Maya culture far to the south,

initially held the predominance in the northern Yucatán. Chichén Itzá

also appears to have been subordinate to Ek Balam at first. The series

of inscriptions at Chichén Itzá reliably dated with Mayan dates begins

with a long horizontal band in the front room of the Red House (Casa

Colorada). In this inscription, its authors differ significantly from

the Ek Balam inscriptions by using a local language form that later

appears as Yucatec Maya.

The inscription first tells of a

ceremony in the year 869 performed by K'ak'upakal K'awiil ("Fire is the

shield of K'awiil"), the prominent figure in the Chichén Itzá

inscriptions. Less than a year later, fire ceremonies were held

involving K'ak'upakal and K'inich Jun Pik To'ok', rulers of Ek Balam,

and an apparently equal member of the Kokom family, known from the

colonial era. K'ak'upakal is last mentioned in an inscription from 890.

The name of his brother, the second major figure at Chichén Itzá, is

tentatively read as K'inil Kopol. Like his brother, he bears a ruler's

title that is not otherwise found, but is only mentioned in inscriptions

between 878 and 881. Her mother was Mrs. K'ayam, while the father

remains unclear with an unsatisfactorily read name, which may correspond

to an emphasis on maternal descent at Chichén Itzá.

K'ak'upakal

and K'inich Jun Pik To'ok' also appear at a monument in nearby Halakal,

presumably with an as yet unidentified local ruler. Also in neighboring

Yula, K'ak'upakal appears, along with the local ruler To'k' Yaas Ajaw

K'uhul Um and others in connection with fire ceremonies. In the Chichén

Itzá building now known as Akab Dzib, Yahawal Cho' K'ak', a member of

the Kokom family, claims to be its owner. But other inscriptions from

unidentified buildings also relate them to the Kokom.

The dates

given in the inscriptions on buildings indicate three construction

periods. The oldest, which predates the rise of K'ak'upakal, includes

the Akab Dzib and Casa Colorada buildings, the next includes the

construction of the Monjas complex. The latter includes the buildings of

the Grupo de la Fecha and the Temples of the Three and Four Lintels, all

commissioned by K'inil Kopol. This also ends the dense sequence of dated

inscriptions. For the later period in which the buildings designated as

Toltec were built, there are no inscriptions that could provide

information about the exact time of construction and the people

involved. One can conclude that the ability to write inscriptions either

no longer existed or was no longer valued.

Numerous names

previously considered members of a relatively egalitarian system of rule

under the Mayan designation multepal are now recognized as names of

gods, rendering the assumed peculiar political structure irrelevant. The

initial misunderstanding stems from the fact that gods and rulers,

possibly only after their death, appear in the same context, primarily

as owners of buildings.

Sylvanus Griswold Morley developed a chronological scheme based on a

literal adoption of the statements of (certain) Chilam Balam texts. Due

to the calendar correlation used, the dates are sometimes around 256

years too late.

948 The Itzá leave Chakán Putum for the northern

Yucatán

987 Itzá resettlement of Chichén Itza, supremacy of Chichén

Itza in northern Yucatán

1224 Conquest of Chichén Itza by Hunac Ceel,

the Itzá are expelled, dominance of the Cocom from Ich Paa over the

Yucatán

1441 Ah Xupan Xiu leads the uprising that destroys Ich Paa,

killing almost all Cocom members

In the 1950s, Alfred M. Tozzer

in particular tried to interpret the statements of the sources more

reliably against the background of the archaeological results available

at the time. Although this reconstruction is viewed critically today, it

can be found in many general representations.

Settlement (the

Chilam Balam texts speak of the "discovery") is put at 692 (Chilam Balam

of Tizimin), 711 or 731 (two sections in the Chilam Balam of Chumayel),

according to the Codex Pérez between 475 and 514, although Tozzer does

not consider any of these dates to be historical. Colonial sources also

speak of a Great Descent (from the East) and a Small Descent (from the

West), with size referring to the number of people. For the Great

Comedown there is (in the Chumayel) even a long list of places starting

with Port Polé on the east coast.

Several texts refer to an

obscure happening around a person named Hunac Ceel, which can be dated

to 1194. According to the Codex Pérez, the chief of Chichén Itzá, Chac

Xib Chac, was expelled because of the underhandedness of Huac Ceel,

ruler of Mayapan. He was driven out by several people with Náhuatl-esque

names. This expulsion was in connection with a banquet given by Ulil,

the lord of Izamal. The strangers were later named Cupul, and they were

encountered by Francisco de Montejo during the Spanish conquest at

Chichén Itza. The story is told somewhat differently in the Tizimin

text: Chac Xib Chac was also invited to the wedding feast of Ah Ulil of

Izamal, as was Hunac Ceel. His deviousness consisted in giving the Chac

Xib Chac a love spell to sniff, whereupon he coveted the bride of Ah

Ulil. War broke out and Chac Xib Chac was expelled from Chichén Itzá.

Sometime, according to Landa, between 1224 and 1444, a Kukulcán

arrived with the Itzá at Chichén Itzá, and later founded Mayapan.

Hunac Ceel was later thrown into the Sacred Cenote of Chichén Itzá,

but he survived and came back with the prophecies and became Supreme

Chief. Ruler was Ah Mex Cuc. Chichén Itzá came to an end in 1461, and

some of its residents moved to the far south island town of Tayasal on

Lake Petén, where they retained their independence until March 13, 1697.

A later view sees the Itzá as an immigrant group who had come from a

more Mexican-influenced area. They reached the Yucatán in the

aforementioned Small Coming Down from the West. Among other things, it

is said of them that they had only a broken command of the Mayan

language. Their leader appears to be Kukulcán (whom earlier research

linked to the Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl of the same name in Náhuatl from

Tula), who is said to have left his country for the Gulf of Mexico. This

is set in the year 987. However, historical analysis of the historical

records cannot clarify what role (if any) played by Toltec immigrants,

warriors, or religious leaders at Chichén Itzá.